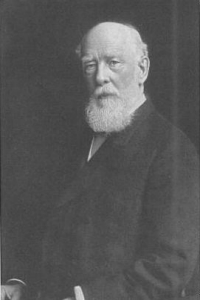

GEORGE W. ATHERTON (1882-1906)

The Person: The 24-year administration of President Atherton vindicated the trustees for the time and care they used in selecting him to be the seventh President of the University. He was born in Massachusetts, and when he was 12 his father died. Through work in a cotton mill and on a farm he earned enough to help support his widowed mother and to pay his way at Philips Exeter. He entered Yale, but withdrew for Union service in the Civil War, and had risen to the rank of captain when his health failed. Returning to Yale, he was graduated in 1863 and taught for several years at Albany Boys' Academy in New York and at St. John's College in Maryland. He was a member of the first faculty of the University of Illinois, which he left to become professor of political science at Rutgers. In New Jersey, he also took a law degree and ran unsuccessfully for Congress. He was at Rutgers when he accepted the Penn State presidency at the age of 45.

The Challenge: To secure recognition and support from Pennsylvania for its land-grant college was Atherton's major goal. Prospects had recently been improving but were still not bright. With firm support from the trustees and the faculty, "a strong President would now have a reasonable chance of building on the newly reconstructed foundation," and Atherton had the experience and qualifications for the task.

The Achievements:

a) Improved public relations received immediate attention. The trustees authorized "the printing of a thousand copies of a circular he had prepared for distribution among educators, Grange officers and others...and voted the sum of $1,500 to advertise the College in 15 leading newspapers and in religious, scientific and agricultural journals." Aided by the political prestige of the board president, General Beaver, Atherton worked with state officers and legislators to alter the "well nigh incredible, but sedulously fostered idea...that the College had no more right to legislative appropriations than had other institutions." With dignity and patience, he clarified facts which had been deliberately distorted by others, and slowly replaced the public's prevailing ignorance and misinformation with a more factual awareness of the College's purpose and potential.

Calling in his inaugural address for a broad interpretation of the Morrill Act, Atherton insisted that the College should be "an industrial and scientific rather than a classical and literary institution.... Classical studies were not to be abolished, but they could not be the 'leading object'...." He also came out strongly for placing the "mechanic arts" on a parity with agriculture in the curriculum, in view of the rise of industrial opportunity in the nation, and especially in Pennsylvania.

Emphasis on industrial and general education aroused the resentment of the farm faction, which was unreconciled to the apparent neglect of agriculture as a course of study and had never fully appreciated the need of agricultural research for instruction or for the development of agriculture as an industry.

This hostility was reflected in the initial attitude of Governor Pattison, who had defeated General Beaver in the bitter 1882 election and also was not well informed about the College or its land-grant relationship to the state. Twice he vetoed bills calling for establishment of an agricultural experiment station at the College. In 1884, at the semi-annual meeting of the Board of Trustees, he "offered a resolution from the floor calling for the reduction of the number of professors by one-half...in recognition of the financial condition of the College and its relation to the agricultural interests of the Commonwealth." The board adopted a substitute resolution appointing a committee of the governor, the superintendent of public instruction and the College President to review the situation "to report what changes, if any, should be made."

The committee's majority report recommending reorganization of the College to make it exclusively agricultural was rejected. Atherton's strong minority report was approved by a vote of nine to five. Eventually winning Pattison's staunch support and friendship, Atherton proceeded to implement his program.

b) Curricular changes. During the first decade Atherton merged the classical course into a general scientific and a Latin scientific course for the bachelor of science degree, expanded the technical work into eight courses for technical degrees, and gradually reached the point of offering (in the 1896 catalog), with these, a classical course for the B.A. degree. Departments were next grouped into seven schools--Agriculture; Natural Science; Engineering; Mines; Language and Literature; Mathematics and Physics; and History, Political Science, and Philosophy. By dividing the liberal arts into three schools, Atherton could emphasize the obligation of a state land-grant institution to provide all students, men and women, with liberal as well as practical, technical education.

To serve other segments of the state's population, several less formal programs were developed:

Short courses (three in agriculture, one in chemistry, one in mining, and an elementary course in mechanics) were offered with no admission requirements and no degree.

Correspondence courses in agriculture grew out of the Chatauqua home study program begun in 1892.

Extension work had its beginning as faculty and staff members participated in the series of Farmers' Institutes held throughout the state each winter.

Summer school began in 1896 as a two-week period of uninterrupted practical training in the laboratories, shops and fields, required of undergraduates in engineering and later in industrial chemistry. This continued through the Atherton administration but is not related to the regular summer session for teachers started in 1910.

c) Increased enrollment reflected the wisdom of Atherton's curricular reforms. When he became President, many of the 87 students were in the preparatory department and were from the immediate neighborhood. When he died in 1906 the enrollment was 800, from all parts of the state and predominantly in baccalaureate degree programs. From 7 in 1882, the graduating class increased to 86 in 1906.

d) Improved financial status came in 1887, a year that proved to be a major turning point in the history of the College. A $100,000 appropriation, which included the first provision for maintenance, passed the Legislature with the support of Governor James Beaver, whose service as a trustee had acquainted him with the significance of the struggling institution for the state. This sum launched the first major building program and has been followed by an unbroken series of appropriations in accordance with the provisions of the Morrill Land-Grant Act. Additional federal funds came when Congress passed the second Morrill Act in 1890 and when the state assigned these and later federal funds to the College as its land-grant institution.

e) The agricultural experiment station was formally established at the College in 1887 under the Hatch Act passed by Congress and accepted by Pennsylvania the same year. Experimental work in agriculture had been conducted from the first years but without adequate organization because of lack of funds. Whitman H. Jordan (1881-1885), the first professor appointed to give full time to this work, began systematic experimentation and published bulletins, but resigned to become director of the Maine, and later the New York, experiment stations. Henry Prentiss Armsby, appointed by the trustees in 1887 as the first director of the station, became internationally known through the studies in animal nutrition he conducted with the respiration calorimeter he built here.

President Atherton had helped to formulate the Hatch Act and was a founder and the first president, in 1887, of the organization now known as the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges. Atherton and Armsby continued to be active at the national level in promoting support for the colleges and experiment stations.

f) Buildings resulting from the appropriations of 1887 and following years included the armory, the experiment station, chemistry and physics (Walker Lab on the site of the present Davey Building), Old Botany, Woman's Building, and Old Engineering. Old Beaver Field was provided for athletic activities, and other improvements included the building of a new tower, roofline and upper floor of Old Main following fire damage in 1895.

The auditorium and Carnegie Library buildings were acquired, largely through the efforts of President Atherton, as gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Schwab and Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Carnegie in the early 1900s when the men were members of the Board of Trustees. Substantial scholarships and loan funds were also begun at that time by the Carnegies and alumnus James G. White '82.

g) Student activities were encouraged and expanded rapidly in the 1880s. The literary societies, founded in 1859, and the YMCA, organized in 1875, continued to be active. Intercollegiate athletics, the yearbook (La Vie), a newspaper (Free Lance, later the Collegian), musical organizations and debating all made a start. By 1900 the Blue Band had been organized and Thespians had given their first performances. The trustees removed their ban on dances and allowed local men's groups, many of them eating clubs, to petition for charters from national Greek letter fraternities. Women had to wait until the 1920s for permission to form local clubs and seek national Panhellenic affiliation.

h. The Semi-Centennial was celebrated in 1905, marked by special events and by a correction in the seal of the College to use the charter date, 1855, instead of the previously used opening date, 1859.

When President Atherton died in July 1906, Penn State had become firmly established and more widely recognized, but much remained to be done to assure continued progress.