On June 22, 1882, the board of trustees unanimously elected George Washington Atherton the seventh president of The Pennsylvania State College, bringing to a close an exhaustive search that had lasted for over a year. For the previous thirteen years Atherton had headed the political science department at New Jersey's land-grant institution, Rutgers College. His own education was in the classical style, however. Born in Massachusetts in 1837, Atherton entered Yale in 1860 but withdrew to serve as an officer in the Union army. After returning to Yale to finish his studies, he taught briefly at St. John's College in Maryland before taking a position as professor of history at a new land-grant institution, the State Industrial School of Illinois (later the University of Illinois).

It was there that Atherton first became intrigued with the idea of combining technical and traditional subjects in a college curriculum. As professor of history, political science, and constitutional law at Rutgers, he conducted the first systematic inquiry into what the Morrill Act had accomplished. Presenting his study at a meeting of the National Education Association in 1873, he refuted the accusations of critics who charged that most colleges were squandering their land-grant endowments and defended the role of state and federal governments in giving financial support to agricultural and industrial colleges.

Penn State's trustees considered themselves extremely fortunate to have secured a man so familiar with and dedicated to the concept of land-grant education. Even in his appearance and demeanor, George Atherton fit perfectly the requirements of a college president. People meeting him for the first time were invariably impressed by his imposing physical presence and the conciseness and authority with which he spoke. He was unfailingly courteous in his personal dealings, yet he maintained an aloofness that seemed to indicate he was more interested in gaining respect than friendship. He was also a realist. "I understand full well that my path is not to be strewn with roses," he wrote in his letter of acceptance to General Beaver. "There will be alert and vigorous criticism at every step, for a good while at least; but if devotion and hard work, and singleness of purpose can accomplish anything, we will win."

When Atherton arrived at the College in July 1882, the legislative inquiry that the school requested earlier had just concluded. Through advertisements in newspapers, personal solicitation, and public meetings held throughout the Commonwealth, the investigative committee invited all who had complaints against the College to come before the committee and put their remarks in the public record. Among the dozens who testified were former and present faculty and trustees, farm superintendents, and alumni. Also given a hearing were a variety of individuals who had no formal connection with the College but who, for one reason or another, wished to see the school lose its endowment or close its doors altogether. Given the drift and instability Penn State had experienced since Pugh's death, the committee's findings could have been devastating. Fortunately, just as the trustees had anticipated, most of the potentially crippling allegations against the College were no longer valid, thanks to the curricular reorganization of 1881 and the change in the institution's leadership.

As a result, the hearings actually served to strengthen Penn State's image by revealing how the College had at last taken decisive action to resolve the problems that had plagued it for so many years. As the investigators themselves said in the report they submitted to the legislature in February 1883, "The College for a long time has been subject to an amount of public criticism, which has resulted in a widespread distrust if not hostility towards it. It is obvious to us that much, if not most, of the feeling referred to, grew out of a condition of things which no longer exist." So impressed were the committee members with the recent reforms instituted by the College that they urged the General Assembly to give more money to the school. Labeling the $30,000 Penn State annually received from its endowment "a mere pittance" in comparison with the public aid other states gave their land-grant schools, they pointed out that since the College was adopting comprehensive courses of study in various technical fields, it would need increased monetary support. "These immediate needs of the College, we believe it would be a sound and wise policy for the state to supply," declared the panel of lawmakers. "Although in its organization a private corporation, it is in every proper sense the child of the state, and we are strongly impressed with the conviction that the time has come when the state should give it such fostering care as will make it not only an object of just pride, but a source of immeasurable benefit to our sons and daughters."

Not everyone agreed that the College was finally on the right track. In 1882 James A. Beaver captured the Republican Party's gubernatorial nomination. Opposing him was the Democratic candidate, Robert E. Pattison, who pledged to eliminate the alleged inefficiencies and corruption of the past several Republican administrations. Since Beaver was closely identified with Penn State, the College inevitably became an issue in the campaign, a situation Beaver had hoped to avert by stepping down as president of the board of trustees. (Francis H. Jordan, a Harrisburg attorney, succeeded him.) The Democrats did not hesitate to attack the College as well as Beaver, and when Pattison won the election, he considered himself obligated to do something about the school's inadequacies.

Desiring to force Penn State to undertake greater economies in its operation, Pattison offered a resolution at the trustees' meeting in January 1884 calling for the eighteen-member faculty to be reduced by one-half. Before the measure could be voted on, other trustees, startled by the extremism of the proposal, persuaded the governor to accept as a compromise the appointment of a three-man subcommittee to examine faculty needs and make recommendations for changes. Two months later, the trustees convened a special session in Bellefonte to hear these recommendations. A majority report, authored by Pattison and Superintendent of Public Instruction E. E. Higbee, urged the abolition of the professorships in civil engineering, physics, and ancient languages, and the appointment of two more teachers in the agriculture department. In a minority report, the third member of the panel, President Atherton, argued that Paulson's plan would return the College to its days as a farm school. it would not only be a clear violation of the Morrill Act, contended Atherton, but it would also bring ruin to the institution, for the agricultural course had thus far attracted only a small fraction of the College's total enrollment.

The trustees recognized the wisdom of Atherton's plea and voted 9 to 5 to accept the minority report. The Pattison affair represented the last serious attempt to preserve Penn State's role as primarily an agricultural school, but it was only the first of many challenges that were to confront George Atherton. The governor did get revenge of a sort later, however. When a bill appropriating money to I the College came before him, he vetoed it, saying that the history of the institution did not justify spending any more state money on it.

President Atherton made plain from the very first the direction in which he hoped to lead the College. "The institution alms to hold the highest rank as a school of technology," he stated in his annual report to the trustees in 1883. Several months later, on the occasion of the inaugural ceremonies that formally marked the beginning of his administration, he elaborated further on the role he expected Penn State to play. "The conclusive fact remains that the vast majority of those who pursue advanced degrees, do so with a utilitarian aim," he proclaimed. "Their primary purpose is not the cultivation of their minds, however desirable that may be, but the acquirement of a means of livelihood; and the call for that kind of education is steadily increasing, with the development of our vast material wealth."

Atherton was describing nothing less than a revolution in the American system of higher education. It was a revolution for which he had the greatest sympathy, although he was not prepared to abandon classical education, which he asserted "furnishes a very high order of intellectual discipline." Nevertheless, as a land-grant institution, The Pennsylvania State College was obligated to give priority to technical education. Since Pennsylvania was the nation's most industrialized state, Atherton was especially eager to expand the engineering curriculum and thus satisfy an important economic need of the Commonwealth. At the same time, the College would be demonstrating to Pennsylvania's citizens the value of maintaining an institution that offered higher education at a cost that persons of even modest financial means could afford.

A baccalaureate program in civil engineering had already been established, and the trustees had also approved the introduction of a two-year course in mechanic arts, which was to consist of instruction in such manual skills as carpentry, woodworking, and metalworking. Atherton believed that the College ought to have a course of study in the mechanic arts that was more appropriate for an institution of higher learning. In the spring of 1883, he asked Louis E. Reber '80, an instructor in mathematics and military tactics, to spend the next year taking graduate work in mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Reber was then to spend a few months inspecting mechanical engineering courses and facilities at several other colleges in the Northeast and Midwest before returning to Penn State, where he would reorganize and upgrade the mechanic arts curriculum. Reber quickly consented to Atherton's proposition, undismayed by the fact that he would have to pay most of his own expenses.

Reber returned to the College at the end of the summer of 1884 and prepared to add to the mechanic arts curriculum subjects of a more theoretical nature. More classroom space was a prerequisite for any expansion, so Reber persuaded Atherton to take $1,600 that Professor Whitman H. Jordan had earned for the College by conducting soil analyses and combine it with a small amount of cash on hand to pay for construction of a mechanic arts building. The two-story, wood-frame structure was situated along College Avenue near the main campus gate. Its modest dimensions (34' X 50') were not proportional to its significance as the first College building to be constructed exclusively for instructional purposes.

Mechanical Arts Building (left) and pump houses on an unpaved College Avenue.

Reber also faced the task of outfitting the building with the necessary equipment. Knowing that Penn State could not afford to spend much money on this hardware, Reber made the rounds of various equipment manufacturers in the Northeast in an effort to induce them to donate machinery to the school, or at least sell it at greatly reduced prices. His argument that an investment in technical education would ultimately yield economic dividends for these manufacturers was a convincing one. Within a year, Reber had obtained all the necessary items to furnish carpentry and machine shops, a forge, and a wood-turning room; the total cost of the equipment was only a small fraction of its $5,000 value. "The Pennsylvania State College now had shops, though small, as well equipped as any I had visited," he later recalled with pride. In the meantime, the board of trustees had approved a baccalaureate program in mechanical engineering to begin in the fall of 1886, with Reber as head.

Students taking either civil or mechanical engineering shared a common course of studies during their freshman and sophomore years with all other students except those in the Latin-scientific course, the new title of the much diluted classical course. Since specialization did not occur until the Junior year, it was not until they had completed two years of undergraduate study that students had to decide which technical course they should enter or whether they should pursue a degree in the general science curriculum. By 1884, students also had the option of enrolling in one of three two-year certificate programs in mechanic arts, agriculture, or chemistry. Total enrollment climbed steadily during the early years of the Atherton administration. Eighty-four students were working toward baccalaureate degrees in 1886-87, more than double the number four years earlier.

The growth in the size of the student body and the need for more laboratory space for the technical courses demanded a physical expansion of the College. All the recitation classes and most of the practicum sessions (with the exception of those in mechanic arts) were still being held in the main building, or Old Main, as it was beginning to be called. In May 1887, the General Assembly allocated $100,000 to Penn State for the construction of new buildings and the improvement of existing ones. The College owed this appropriation-its first in nearly a decade-in part to Atherton's cultivation of good relations with the Commonwealth's political leaders. The election of James A. Beaver as governor in 1886 also did much to insure receptive consideration in Harrisburg of Penn State's needs. But of greatest consequence was the fact that the College now offered the kind of utilitarian education that Pennsylvania's citizens could appreciate and were willing to support. The depth of this support was evident in 1889 and again in 1891, as the legislature voted a total of $277,000 for more buildings and general maintenance. Even Robert Pattison, who served his second term as governor upon succeeding Beaver in 1891, became a friend of the College.

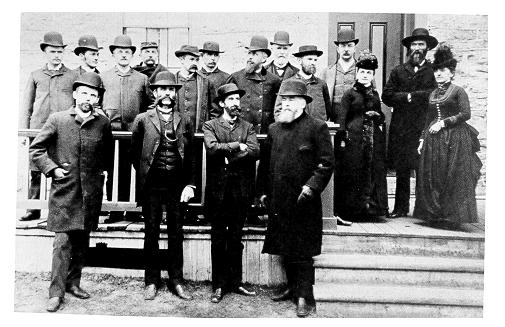

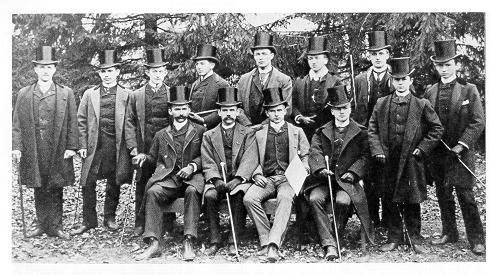

The faculty in 1887. The front row includes (from left to right) Louis Reber, I. Thornton Osmond, William A. Buckout, and George Atherton.

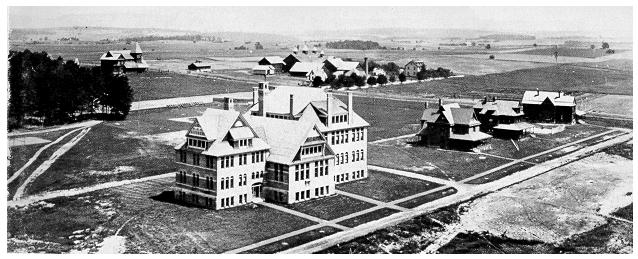

The first structure to be erected with state money was the Botany Building, followed by the Armory, the Chemistry and Physics Building, a ladies' cottage, and a half dozen professors' residences. As more space became available in Old Main, renovations were undertaken there to enlarge the chapel (which, in spite of its name, was used for a variety of large public gatherings), boosting its seating capacity to 600. Electric lights were also installed throughout the building. The agriculture department benefited from both state and federal assistance, as Congress in 1887 passed the Hatch Act making funds available for the establishment of agricultural experiment stations at land-grant institutions. On June 27, 1888, Governor Beaver and the newly appointed director of Penn State's agricultural experiment station, Dr. Henry P. Armsby, laid the cornerstone of that structure on the gentle slope of what soon would be known as "Ag Hill." State funds were used to construct a creamery and dairy building nearby. The Pennsylvania legislature assisted the agriculture department and the entire College when in 1887 it provided for the sale of the eastern and western experimental farms, which had for so long been financial drains and the objects of so much criticism.

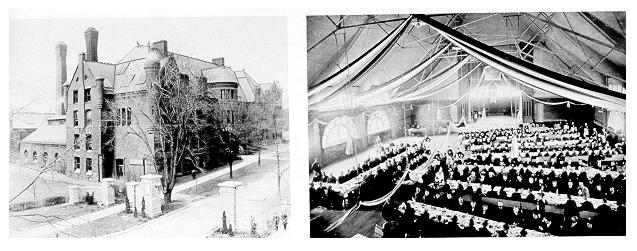

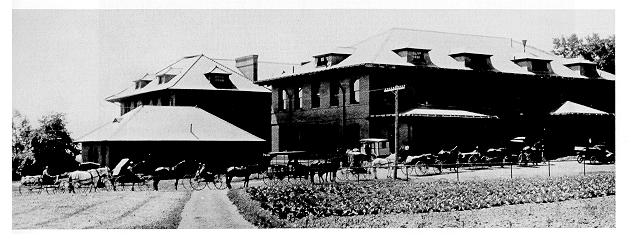

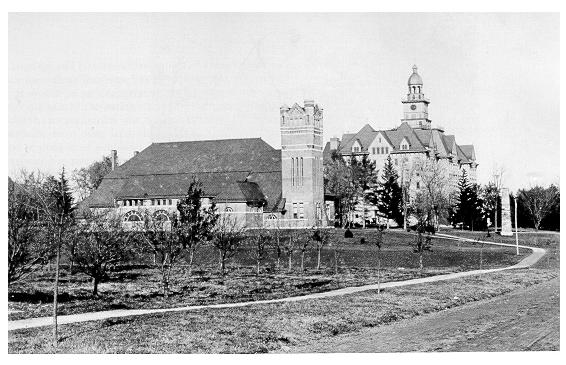

The architectural zenith of the building program came in 1893 with the dedication of the Main Engineering Building. On February 22 several hundred students, faculty, and friends of the College gathered in the chapel to hear speeches by President Atherton, Governor Pattison, U.S. Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble, and several other dignitaries marking the formal opening of the building. The occasion attracted more favorable publicity than Penn State had received for many years and justifiably so, for the engineering edifice was a magnificent one. Located a short distance from the main gate, the three-story Romanesque structure was designed by Pittsburgh architect Fred L. Olds and composed of red brick with brownstone trim. Connected to the lower side of the building was the new campus power plant, which did double duty as a generator of steam heat and electricity for the College and as a laboratory for engineering students. General Beaver sounded the keynote of the dedication. "The aim and outcome of the old university was the doctor," he proclaimed. "The aim and outcome of the new university is the engineer!"

Many students shared Beaver's sentiments, just as President Atherton had anticipated. In 1893-94, 128 of the 181 undergraduates at the College were pursuing engineering degrees. That year witnessed the introduction of baccalaureate programs in mining engineering and electrical engineering. The new Department of Mining Engineering offered specialized options for juniors and seniors in metallurgy and in practical mining engineering. Instruction in the field of electrical engineering had already been given for several years under the electrotechnics option of the Department of Physics, which itself had been detached from the old Department of Chemistry and Physics in 1888. But as Pennsylvania and the nation now entered the "age of electricity," Penn State followed the example of the best private technical schools and created an independent Department of Electrical Engineering. The curriculum covered such diverse topics as electricity and magnetism, telephones and telegraphs, electric lighting, and electric motors.

The physics course suffered a substantial drop in enrollment when the Department of Electrical Engineering was created, because the majority of physics students were interested primarily in electrotechnics. Even chemistry, a mainstay of the curriculum since the days of The Farmers' High School, attracted relatively few students in comparison to those choosing engineering. Part of the Department of Chemistry's troubles initially stemmed from the less than satisfactory performance of both students and teaching staff. Then in 1889 George Gilbert Pond, a graduate of Amherst College and the University of Gottingen, arrived to assume the duties of professor of chemistry and head of the department. Pond, who would go on to become a legendary figure at Penn State, sternly announced that "no inferior work can be accepted here" and proceeded to reorganize the chemistry course. Although enrollments remained modest, Pond's high standards drew enough students to the chemistry course (about twenty or so every year) to make it for many years the most popular of the non-engineering courses.

Seen from Old Main are the newly completed Chemistry and Physics Building (later Walker Laboratory), three faculty residences, and (left rear) the agricultural experiment station.

Ironically, it was the agricultural course that drew the fewest students. From the curricular reorganization of 1881 until 1893-94, the number of students working toward degrees in agriculture never exceeded five in any one year. President Atherton attributed this situation mainly to the increasing industrialization of Pennsylvania, explaining in a report to the trustees that "the market demand for highly educated scientific men is not so great in agriculture as in many other employments." However, mere enrollment figures did not accurately reflect the important role agriculture continued to play at Penn State, even as the demand for engineering graduates reached unprecedented intensity. The agricultural faculty carried on the only scientific research worthy of the name, beginning in 1881 when agricultural chemist Whitman H. Jordan joined the staff and initiated his much celebrated series of experiments with fertilizers. Jordan laid out 144 soil plots of one-eighth acre each, carefully recorded what types of crops were sown in which plots, and noted the kinds of fertilizers used. The Jordan fertility plots were the American counterparts of the plots at England's Rothamstead experiment station, where Evan Pugh had conducted research.

Coincidentally, Jordan was the first scientifically trained agriculturalist to serve at Penn State since Pugh. Most Pennsylvania farmers were still suspicious of scientific agriculture and, according to Jordan, spent too much time on manual labor and not enough on reading and observation. To encourage farmers to discard time-worn ideas and adopt new approaches to their work, Jordan in 1882 began issuing, free of charge, short bulletins reporting the results of his work with the fertility plots. "The average farmer in Pennsylvania got, in return for cultivating an acre of land, less than $16 total income," he wrote in justifying the need for widespread distribution of the bulletins. "The farmers of Pennsylvania must come to see that brains, not brawn, is to be the moving power in the future."

Jordan also advocated the establishment of a state agricultural experiment station at the College, similar to ones in successful operation in New York and New Jersey. He obtained backing from the state agricultural society, but when the General Assembly passed a bill authorizing such a station, Governor Pattison vetoed it. Jordan resigned in disgust and left Penn State to head the new Maine experiment station. Two years later his goal was achieved, thanks to the support of the federal government through the Hatch Act. The College's new experiment station gave further impetus to the research interests of the faculty, who followed Professor Jordan's lead by writing bulletins describing the nature of their investigations and possible benefits to the Commonwealth's farmers. The agriculture department reached thousands of additional farmers through home correspondence courses, begun in 1892 at the suggestion of Professor Armsby, and through a series of short courses held on the campus during the winter months dealing mainly with various phases of dairying, Pennsylvania's single most important agricultural enterprise.

Of the two nontechnical courses, the general scientific was the more popular, although both it and the Latin-scientific course together accounted for barely ten percent of annual enrollments. Both courses consisted of a smattering of mathematics and the physical and natural sciences. They differed principally in that the general science curriculum highlighted the study of modern languages and literature, while the Latin-scientific emphasized ancient languages and literature. According to the College catalog, either course would "furnish an effective equipment for the duties of American life and citizenship" and prepare the student "to enter successfully upon any chosen career." Technical and nontechnical courses alike required prescribed numbers of credits in such fundamental subjects as English, history, and economics, as well as in those last vestiges of classicism, philosophy and rhetoric. Students usually had few, if any, elective subjects until reaching their junior year, and even then the number was very limited.

Dinner in the Armory (right) followed dedication of the Main Engineering Building (left), February 22, 1893.

In 1884 a two-year ladies' course was initiated. Women were still eligible for admission to any curriculum on the same terms as men, but the ladies' course, explained the College catalog, "contains more of the branches of study that are thought likely to be especially serviceable to them, with less extended requirements in mathematical and scientific studies." Most women attending Penn State during this period preferred to work toward baccalaureate degrees, however, and the ladies' course was eliminated from the curriculum in 1892.

By the mid-1890s, Penn State had come to resemble the modern college in many respects. Technical education was now accepted as a legitimate constituent of higher learning. Laboratory instruction had long since superseded manual labor as part of the curriculum. Research, albeit still confined to agricultural subjects, had nevertheless established itself as a worthwhile activity for the faculty. Administratively, too, the College had matured. The curricular reorganization of 1881 led to the creation of departments as independent administrative units.

In 1895, the College took another giant step in its modernization when President Atherton grouped the various departments into seven schools: Agriculture, Henry P. Armsby, Dean; Engineering, Louis E. Reber, Dean; History, Political Science and Philosophy, George W. Atherton, Dean; Language and Literature, Benjamin Gill, Dean; Mathematics and Physics, I. Thornton Osmond, Dean; Mines, Magnus C. IhIseng, Dean; and Natural Science, George G. Pond, Dean.

The establishment of schools improved coordination of subject matter among the departments having interests in the same or similar disciplines and permitted the development of more systematic programs of instruction for the students. In addition the deans, rather than the president, now had the responsibility for scheduling classes and assigning faculty to teach them, and for administering discipline to students who failed to meet academic requirements. The formation of schools did not affect the curriculum. In 1895 a student could elect to earn a degree in any one of these twelve courses of study: classical; general scientific; Latin-scientific; agriculture; biology; chemistry; civil engineering; electrical engineering; mathematics; mechanical engineering; mining engineering; and physics. This arrangement of schools, departments, and courses of study was to remain the core of Penn State's academic program for the next ten years.

CHANGES IN STUDENT LIFE

Just as the Atherton era marked the emergence of a modern college in the academic sense, so was it a time when extracurricular activities came of age. During the early years of the school, students had to rely on their own ingenuity to relieve the tedium of their isolation. With chapel, manual labor, evening study sessions, and other supervised activities consuming much of their time, students had few idle hours to contemplate their boredom. The Washington and the Cresson literary societies remained the only student organizations until 1875, when James Calder helped to establish a branch of the Young Men's Christian Association. While the YMCA provided a welcome outlet for purely social gatherings, its Bible study classes and prayer sessions resembled the kinds of programs already offered to the student body.

Civil engineering students practice surveying a railroad right of way, 1894. Mechanical engineering students machine parts on a speed lathe, 1894.

No formal athletic activities existed. From time to time a few of the boys from the Philadelphia area gathered on the lawn near Old Main for a game of cricket. A more popular sport was baseball, with games pitting a squad from the College against teams from neighboring communities. Baseball gave rise to Penn State's first athletic hero, John M. "Monte" Ward of Bellefonte, who left the College in 1877 before graduating to play professional baseball for the New York Giants and several other teams. Ward became one of the first pitchers to perfect the curve ball and compiled such an impressive record on the mound and at the plate during his sixteen-year career that in 1945 he was inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame. Football, a sport then in its infancy, evoked only mild interest. In 1881, thirteen students traveled to Lewisburg to beat a Bucknell University team 9 to 0; but the rules governing play made the game more akin to rugby than today's gridiron clashes, and no further matches with other schools were scheduled.

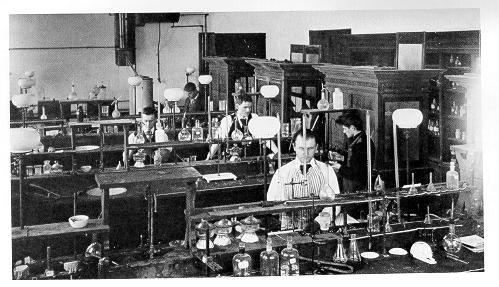

Quantitative laboratory, Chemistry and Physics Building

Not until 1887 did Penn State catch the football fever that was raging on many eastern college campuses. On November 12, its team set out for Lewisburg to do battle with Bucknell. That game, which the visitors won 54 to 0, was played under modern rules and has come to be regarded as Penn State's first official intercollegiate football contest. Over the next few years, Penn State played other Pennsylvania college teams and a few squads fielded by preparatory schools. Baseball, basketball, and track were all part of Penn State's intercollegiate schedule by 1896, but none matched football's ability to arouse excitement and enthusiasm among the students.

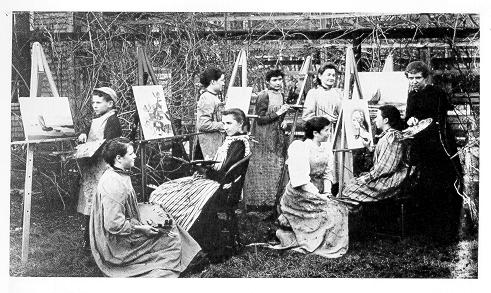

Women's art class in an outdoor studio, mid-1890s.

Despite football's sway over the students, initially neither faculty nor alumni took an active interest in the sport, leaving the burden of organizing and financing the games to a student-run Athletic Association. No admission was charged to home games. The team played at other schools for expense money only-usually $30 to $40, or just enough for railroad fare-and often financed the appearance of visiting squads by soliciting donations from local merchants. The players also furnished their own equipment, a necessity that indirectly led to the adoption of college colors. Before leaving for the Bucknell contest in 1887, the Penn State players decided that they should have some sort of uniform in place of the motley outfits they usually wore. The squad selected pink and black for its new jerseys and pants. The sun and several launderings soon bleached the pink to white, making a change in colors imperative (but not before a good many students had purchased pink and white striped blazers with matching straw hats). The Athletic Association's new selection, made in 1890, was dark blue and white, a combination later approved by the student body as the College's official colors.

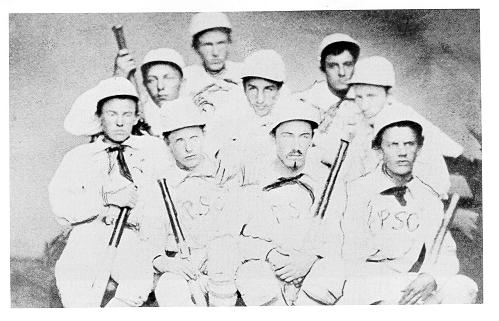

Baseball team of 1875. John M. "Monty" Ward is at far left. A campus penman has "touched up" the photo, perhaps altering some of the faces.

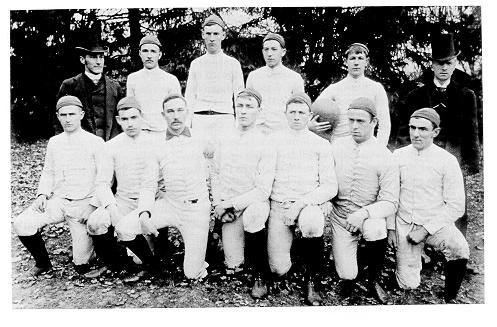

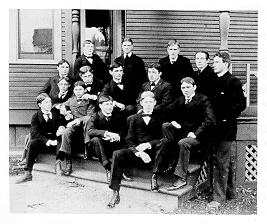

The first Penn State intercollegiate football team, 1887.

During its first several seasons, the football team lacked a regular coach. In 1892, in response to a petition signed by ninety-two undergraduates declaring that "good standing in athletics would widen the reputation of the College," the board of trustees directed President Atherton to hire a director of physical training. Atherton appointed George W. "General" Hoskins, a talented amateur athlete and former athletic trainer at the University of Vermont. In addition to supervising a program of physical exercise for all the students, Hoskins was assigned the job of directing the College's intercollegiate sporting activities. The College also began upgrading its athletic field (located about where Whitmore Laboratory would later stand). A 500-seat grandstand was added along with complete facilities for baseball, football, and track. Christened Beaver Field, it was ready in time for the 1893 football season. Six years later, the Athletic Association received permission to collect an annual fee of five dollars from each student to help meet expenses of intercollegiate games.

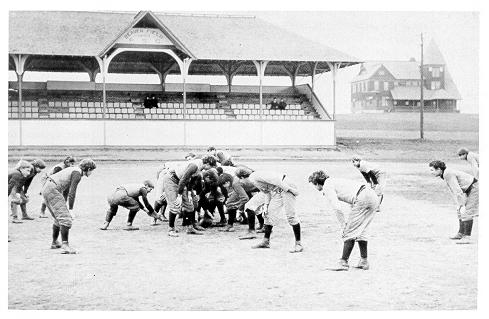

Football practice on (old) Beaver Field.

Athletics was only one contributor to the development of a strong school spirit. Another was the publication in April 1887 of the Free Lance, the first student journal to be issued regularly. Containing twelve pages and selling for fifteen cents per copy, the monthly Free Lance was the product of the combined efforts of the Cresson and the Washington literary societies. The societies' support notwithstanding, the editors vowed in the first issue not to lay before their readers "a lot of dry literary and moralizing matter." Instead, they intended to publish a journal composed of news and commentary on current events at the College and in the world at large, interspersed with notes on the alumni and occasional literary endeavors. Typical of the material found in the Free Lance in its early years are these excerpts from its "locals" column:

- In the Botany practicum, during the professor's absence, the "kid," trying hard to amuse the class, inserted a lighted cigarette into the skeleton's mouth. The prof, on returning, promptly told him to remove the cigarette, as that perhaps was the cause of the skeleton's presence among us.

- Dr. A. J. Orndorf of Pine Grove Mills has opened a branch office at State College, where he is prepared to do all kinds of dental work in a first-class manner.

- We would like to call the attention of the college students to the paths that are being worn all over the campus; as there has been no rain for some time, the sod is very easily tramped out, and if it is not stopped, our pride will soon resemble a railroad map.

- The members of the football team take a six-mile hike every morning before breakfast, and then come in and devour a leg of mutton, six hard boiled eggs, fourteen rounds of bread, and five pounds of oatmeal apiece, without mentioning such little things as butter, coffee, etc., etc. Already the hotel keepers are considering the advisability of petitioning the faculty to have the destructive game stopped.

In 1895 the Free Lance reversed its policy of covering local news in favor of becoming a vehicle for literary pursuits. Not until 1904, when the State Collegian succeeded the Free Lance, did the College again have a student publication of current events.

A second milestone in student publications occurred in 1889 with the appearance of the first edition of La Vie, the College yearbook. Declaring their wish "to establish a custom which shall be followed by each succeeding class upon its advent to the junior year," La Vie's editors compiled a series of faculty biographical sketches, class histories, a summary of the year in athletics, and assorted poems and cartoons. Its format experienced many modifications over succeeding generations, but La Vie continued to be a project of the junior class until 1930, when it passed into the hands of the seniors.

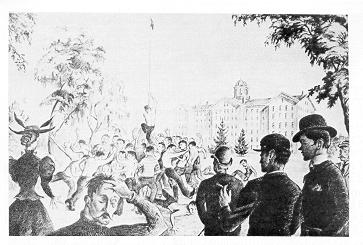

Freshmen and sophomores battle in a flag scrap. Drawing by AWC (Andrew W. Case?) from a Corner Room menu.

Eventually, undergraduates of all levels helped to, produce La Vie and the publication began to record activities of general interest at Penn State, although it remained primarily a senior yearbook.

Born at about the same time as the Free Lance and La Vie were the class scraps. A scrap was a good natured but often brutal encounter between large numbers of freshmen and sophomores. One of the first was a bone-crushing affair known as the cane rush, the object of which was to see whether freshmen or sophomores could get the most hands on a cane. Among the most memorable was the annual picture scrap, wherein the freshmen attempted to assemble for a class photograph without allowing word to leak out to the sophomores, who were obligated to break up the affair. So determined were the sophomores to do their duty that once the alarm was sounded, they did not hesitate to desert their classrooms in order to rush to the scene of an impending freshman portrait. Once there, the intruders used any means at their disposal to disrupt the portrait session. Injuries inevitably resulted, with the hapless photographer more often than not suffering right along with the freshmen. At the very least the combatants sustained torn clothing, black eyes, and assorted bruises.

After every scrap, one student remembered, "tailors were in demand, the odor of arnica was distinguishable throughout the community, and the quarters of the participants might have been mistaken for apothecary shops." Hazing of freshmen and a formal set of freshman customs had not yet become widespread. In their absence, the scraps helped to initiate incoming students into the life of the College.

Before being admitted to the freshman class, prospective students had to give evidence of meeting the College academic standards. Day-long entrance examinations were held in June and September at the College and at Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and any other community where five or more applicants assembled. Written questions covered a broad range of subjects, with emphasis on English grammar, geography, history, mathematics, and physics. Students who

I had graduated from normal schools or from a select group of high schools and preparatory academies whose scholastic standards the College had judged to be outstanding were exempt from those tests and evaluated on the basis of their previous scholastic attainments. Tuition, abolished under President Calder, still had not been reinstated for Pennsylvania residents. Nonresidents paid $100 annually. The College did levy fees of $17 per academic year (consisting of fall, winter, and spring sessions) for heat, light, and janitorial expenses and $5 as a refundable deposit against damages. Dormitory rooms in Old Main typically ranged in price from $56 to $73 for a year, with students residing off campus paying a similar amount. The College did not provide food service for male students, who for about three dollars a week could obtain their meals at the local hotel or at one of a half-dozen boarding houses.

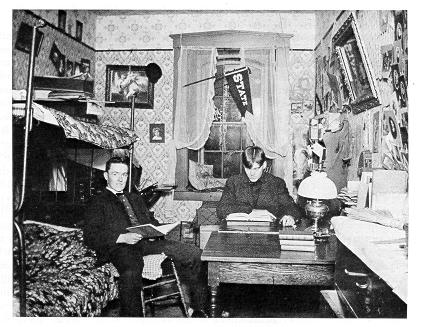

Student quarters in Old Main, about 1901.

Most women students lodged in the west wing of Old Main until 1889, when a three-story Ladies' Cottage was erected. The building owed its construction largely to the agitation of Harriet M. McElwain, since 1883 lady principal and instructor in history, who complained of the primitive living conditions found in the main building. In the Ladies' Cottage, women had the opportunity to gain practical experience in "domestic economy," a forerunner of home economics. The move into new quarters did not bring with it a relaxation of social regulations. Female students were still prohibited from receiving male callers without permission and were otherwise isolated from many facets of College life. So entrenched was the ban on women at campus dances, for instance, that it was not lifted until 1890, and even then an act of the board of trustees was needed. Another concession to changing mores occurred that same year when President Atherton and Miss McElwain opened the parlor of Old Main to both sexes on Wednesday evenings until nine o'clock. While the students were most assuredly chaperoned, they at least could mingle freely without having to secure special permission beforehand.

Both male and female students were still compelled to adhere to a rigid code of conduct. "The discipline of the College is intended to be strict, but reasonable and considerate," warned the College catalog. "It assumes that students come here, not to spend their time in idleness, but to prepare themselves for useful and honorable careers in life. Those who are not disposed to support heartily a discipline of this kind ARE URGED NOT TO APPLY FOR ADMISSION." The administration utilized a system of demerits called censure marks to enforce its disciplinary policy. Censure marks could be handed out for everything from missing class to smoking on College property to passing a note to a student of the opposite sex. When a student accumulated 60 marks, President Atherton sent a letter to his parents (rarely to "her" parents since young ladies were not as disposed to violate regulations) informing them that their son was in imminent danger of suspension.

Much of the emphasis on discipline was derived from the military regimen that permeated student life in the late nineteenth century. The Atherton administration, if not the student body, took seriously the Morrill Act's call for military training, which by the late 1880s had become quite systematic. All able-bodied male undergraduates were organized into companies and battalions, each with its own student officers, who conducted room and uniform inspections each morning and supervised infantry drills four times weekly. Students also regularly performed artillery drills using several Civil War cannons on Old Main lawn, although the guns were rarely fired during those exercises. (That they were nonetheless capable of being discharged was manifested with startling certainty in 1876, when an undergraduate fired a load of sod through President Calder's office window, and again in 1890, when a few students, evidently ardent Democrats, shot off a cannon in honor of the election of Governor Pattison.) An officer detailed from the regular Army and holding the title of professor of military science and tactics conducted classroom and field instruction.

The Morrill Act and subsequent legislation was vague as to what specific purpose was to be served by all this training, and after four years of drill and instruction, students received no special opportunities to pursue a career in the military. For a few years, some graduates could qualify for commissions in the Pennsylvania National Guard, but even this privilege was revoked by the turn of the century.

Despite the strictness of the disciplinary code-which was not inordinately harsh for its era-President Atherton enjoyed a good rapport with the student body. He demonstrated his willingness to give students a fair hearing by his response to requests that the establishment of fraternities be allowed. At first Atherton shared his predecessors' distrust of these organizations. However, he gradually came to see that because of Penn State's isolation and consequent lack of social outlets, and because of the limited amount of residential space available in private boarding houses and in Old Main, the time was appropriate to recognize fraternities as a worthy component of college life. Atherton also realized that the concept of fraternities had matured over the years, and that they had proven successful at many other colleges and universities. The president recommended to the trustees that the proscription on fraternities be removed. The board approved his recommendation in January 1888, and by the end of that year chapters of the national fraternities Phi Gamma Delta and Beta Theta Pi had been founded, while the formerly secret Latin letter society QTV (later Phi Kappa Sigma) also gained official recognition.

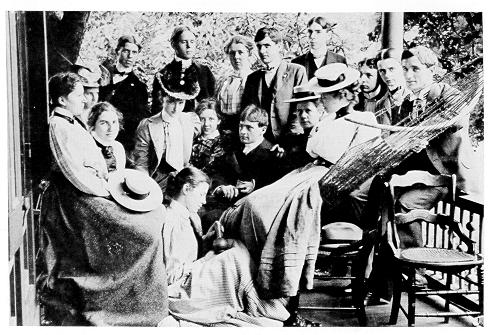

Socializing on the porch of the President's House, 1898.

Again reacting partly to student sentiment, President Atherton in 1892 changed compulsory Sunday chapel service from 3:00 P.M. to 11:00 A.M. and persuaded the trustees to shorten the academic year from 38 to 36 weeks. The students reciprocated by according Atherton a level of respect and affection surpassing that given to any president since Pugh. The only incident to mar the otherwise harmonious relations between Atherton and the faculty and the student body of that era occurred in 1889. Sophomore Charles H. Musser had gone home to Johnstown for a brief vacation over Memorial Day-at the very time that community was hit with torrential rains and floods. Musser returned late to the College, blaming his tardiness on high waters.

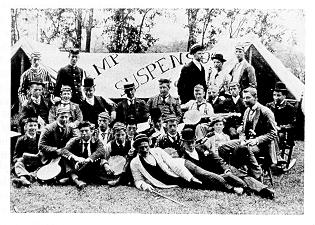

News of the disastrous Johnstown Flood had not yet reached Penn State, so the faculty refused to accept Musser's excuse and suspended him. In retaliation for what they considered to be unfair treatment of their comrade, most of the other sophomores refused to attend classes and were likewise suspended. In a demonstration of solidarity, the sophomores left their regular quarters and pitched tents in the fields west of the campus, christening their new community, "Camp Suspension." Just as the rebels were beginning to have second thoughts about their act of defiance, word arrived of the magnitude of the Johnstown tragedy. The students, including "Calamity Musser," were readmitted, and the hard feelings on both sides disappeared as quickly as they had arisen.

YEARS OF STEADY GROWTH

The College registered modest but steady gains in enrollment until about 1900; thereafter the annual increases were of a magnitude unprecedented in the institution's history. In 1894-95, 221 undergraduates were in residence, a figure which rose to 281 five years later. By 1904-5 the undergraduate population had soared to 637 and was showing an increase of over 100 students annually. The engineering courses continued to be the prime academic attraction, accounting for three-fourths of the student body in an average year. The Department of Electrical Engineering alone enrolled more students than all the non-engineering courses combined. In 1900, only five years after its formation, Penn State's School of Engineering ranked tenth among nearly a hundred engineering institutions in the United States in the number of undergraduates enrolled. The engineering curriculums enabled Penn State to furnish large numbers of persons having the kind of technical knowledge that Pennsylvania, with its countless mines, mills, and railroads, depended on for its economic livelihood.

Men of the secret Latin letter society QTV.

An unfortunate side effect of the emphasis on technical education was the gradual decline in the number of women attending the College. Other than Carrie McElwain (Harriet's younger sister), who received a degree in civil engineering in 1893, no coed manifested much interest-at least overtly-in the technical subjects. Many decades would pass before engineering and the sciences were thought to offer careers suitable for females. With its technical courses overshadowing all other curriculums, Penn State counted only five female undergraduates by 1904-5.

As the student population grew and as employer demand increased for graduates having specialized knowledge, the College's technical offerings became more diverse. Undergraduates in the School of Engineering could opt for two years of concentrated study in such varied fields as railway mechanical engineering, telephone engineering, electric railway engineering, and light, power, and signal engineering. The Departments of Electrical Engineering and Civil Engineering launched baccalaureate curriculums in 1904 in electrochemical engineering and sanitary engineering, respectively, as Penn State became one of the first institutions in the United States to award degrees in either of these fields. The School of Engineering's efforts to improve the quality and range of instruction also led to the introduction of the College's first summer sessions. After President Calder restructured the school year, the campus lay almost deserted between June commencement and the beginning of the fall term in late August. In 1894 Dean Reber prevailed upon President Atherton and the trustees to approve an annual two-week summer school for freshman, sophomore, and junior engineering students to start immediately after commencement. During this period, students received training in field work that they were unable to obtain during the regular school year.

Industry's need for employees able to apply technical knowledge also had an impact on more purely scientific studies. The principal curricular innovation in the School of Natural Science was the creation in 1902 of a four-year program in industrial chemistry, administered by the Department of Chemistry. The new curriculum produced graduates who were conversant with engineering fundamentals and had a thorough background in chemistry. Dean Pond had been campaigning for such a course, which he originally intended to call chemical engineering, since 1895.

Because the demand for specialized curriculums came from industry, agriculture was slower to narrow the focus of its courses of study. In 1905, students could choose a four-year course in general agriculture or could concentrate during their junior and senior years in agricultural chemistry, dairy husbandry, or horticulture. The School of Agriculture did make available an increasing number of short courses during the winter months, with the creamery course being the most popular. Agriculture was as yet the only school to offer correspondence instruction, which was proving to be extremely popular. Over 4,500 citizens from 30 states and the province of Ontario had by 1905 enrolled for courses on topics as varied as beekeeping, cheese making, the use of commercial fertilizers, and farm bookkeeping. The School charged no fees for these courses; students paid only the postage to return their completed lessons for review by the faculty. The chance to learn by mail proved a great boon to farmers throughout the Commonwealth who had neither the time nor the money to come to the campus even for a short time; and although they carried no college credit, the courses enabled many individuals who had already received some education in agricultural subjects to broaden their knowledge even more.

Agriculture was the field in which Penn State offered its first graduate work. Two students received the degree of Master of Scientific and Practical Agriculture in January 1863. Nearly a decade passed before graduate degrees were again awarded, and not until the engineering courses became firmly established were they conferred with regularity. In the early days, graduate studies were tailored to the individual student's needs and interests by the professor supervising his work. Much of this study was by necessity of an independent nature, since the College did not have formal classes for graduate students and only in agriculture did research facilities exist.

Members of Phi Gamma Delta, Penn State's first officially recognized fraternity.

Camp Suspension.

In the 1890s, the College attempted to make graduate work more systematic. A rough uniformity of academic standards was instituted among the various disciplines, and a thesis was required of all candidates for advanced degrees. Responsibility for planning the thesis and the curriculum remained the responsibility of the student and his faculty advisor. With the exception of students pursuing the Master of Arts degree, the College did not require graduate students to do their work in residence. Following the custom of many other engineering and scientific institutions, Penn State conferred technical degrees-Master of Science, Civil Engineer, Mechanical Engineer, Electrical Engineer, and Engineer of Mines-on students who completed either one year of resident studies and a thesis, or three years of professional work in the field in which the degree was to be awarded and a thesis based on this professional experience.

Even after graduate studies became more formalized, until about 1900 usually no more than three or four students received advanced degrees each year. The demand for students holding graduate degrees, especially in engineering, was not great. Technological progress did not yet depend heavily on expanding the frontiers of knowledge. Therefore, employers sought students who could use what they had already learned to solve practical problems. Further training, if needed, was acquired on the job, not in the classroom. There was little economic incentive to pursue graduate studies. Most of those who did earn advanced degrees from Penn State (and most other technical institutions) during this era did so on the basis of their professional accomplishments rather than through the more expensive and time-consuming process of resident study. Other reasons for the dearth of graduate students were the College's lack of adequate laboratories and other physical facilities which could be utilized for research and lack of faculty who had the opportunity to conduct graduate-level research. What resources Penn State did possess barely satisfied the needs of the burgeoning undergraduate population.

In the School of Engineering could be found the most elaborate and costly hardware. The Department of Electrical Engineering, for example, began operating an experimental electric railway in 1896, featuring a small trolley car running on 600-volt direct current. A contact wire was erected above the right-of-way of the Bellefonte Central Railroad (which reached the College in 1892 from its namesake community, where it connected with the Pennsylvania Railroad) from the rear of the Main Engineering Building about a mile westward to the wye at Strubles (near what would later be the thirteenth hole on the White golf course). The Department of Civil Engineering's hydraulic laboratory, one of the best equipped among land-grant and state institutions, paved the way for the pioneering course in sanitary engineering. In the basement of the Main Engineering Building rested the single most expensive piece of laboratory apparatus in the entire College, the huge Reynolds-Corliss triple expansion steam engine. This machine, used for illustrative and experimental purposes in thermodynamics, sold on the commercial market for about $10,000; but Louis Reber had obtained it at a discount of twenty percent after convincing the manufacturer of its educational benefits.

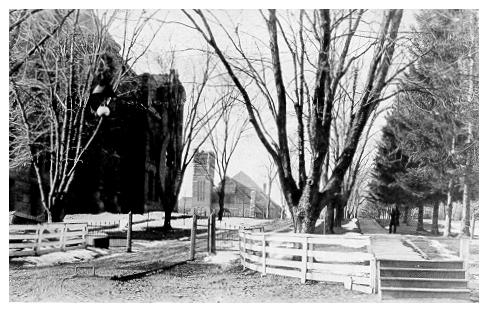

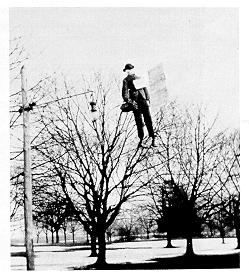

Main entrance to the campus at the corner of College Avenue and Allen Street, 1896. A newly installed arc lamp is at upper lamp, while in the lane in front of the gate is a mechanism that opens the gate automatically when tripped by the wheel of an approaching vehicle.

The School of Agriculture did not need such costly gear. It had over 200 acres of orchards, pastures, vineyards, and gardens, most of which had been in use continuously since the establishment of the central experimental farm in 1867. Students received instruction in all of the fundamentals of scientific agriculture, but the school was particularly well equipped for the study of natural and artificial fertilizers; milk, meat, and butter production; and fruit growing. These strengths reflected the professional interests of Dean Henry Armsby and his associates at the Agricultural Experiment Station. Before coming to Penn State, Armsby had been associated with state agricultural experiment stations in Wisconsin and Connecticut, as well as with agricultural education at Rutgers, where Atherton had first made his acquaintance. Since Pennsylvania was primarily a grain-producing state, Armsby observed, its farmers exported the fertility of their soil along with their grain. Therefore, Penn State's agriculturalists should devote much of their attention to two basic tasks: devising more effective and economical fertilizers to compensate for the heavy demand on the soil and promoting the more efficient rearing of livestock as a profitable alternative to grain production.

Armsby himself was active in the field of animal nutrition and had accumulated such a record of achievement that the United States Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Animal Industry in 1898 offered to assist him in constructing a respiration calorimeter at the College. Completed in the winter of 1901-2, the calorimeter was housed in a small, heavily insulated brick structure not far from the experiment station. It consisted of an airtight, triple-walled box in which a cow could be confined, along with instruments for measuring the amount of food, water, and gas taken in and expelled by the animal. In this way, the net energy or production value of feed could be determined. The first facility of its kind in the world, the calorimeter was useful in the development of improved livestock feed and brought worldwide recognition to Armsby.

About midway between the experiment station and Old Main stood the Chemistry and Physics Building, an imposing, three-story red brick structure shared by Dean G.G. Pond's School of Natural Science and Dean I. Thornton Osmond's School of Mathematics and Physics. Laboratories occupied the basement and attic floors. The Department of Chemistry consistently enrolled more undergraduates and was better equipped than any other department outside the School of Engineering. Its assay and quantitative laboratories and balance room had to be outfitted mainly with hardware imported from Germany, in the absence of satisfactory domestic sources of scientific instruments.

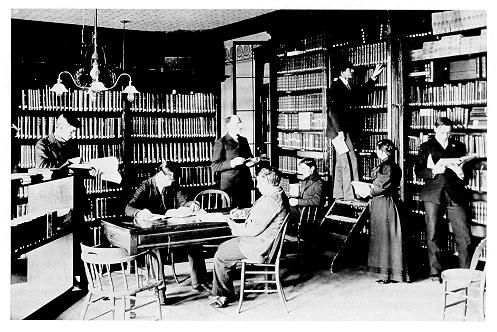

Another important resource for students regardless of their academic interests was the library. The College had for many years taken a casual approach to its collection of books, periodicals, and other written material. As late as 1878, the library contained barely 2,000 volumes, had no room exclusively its own, no regular hours of operation, and was staffed on a part-time basis by one of the faculty. With the appointment of Professor of Modern Languages Charles F. Reeves as part-time librarian in 1879, conditions improved significantly. Among other things, Reeves established regular hours of service, implemented a classification system, and enlarged the collection. In 1896, when Helen M. Bradley became the full-time librarian, the library contained 12,000 volumes and had its own quarters in the central wing of Old Main.

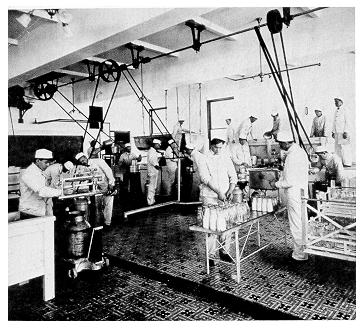

Short-course students in the new creamery, about 1907.

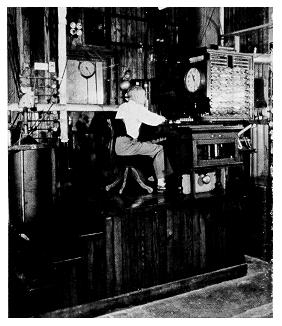

Although this view of the calorimeter dates from 1955, the apparatus was virtually unchanged from the time Henry Armsby used it a half-century earlier.

President Atherton wanted the library to play an even more important role in the work of the College, for now that the technical courses had taken firm root, he was eager to amplify instruction in the liberal arts. "It is greatly to be desired that this side of the institution be developed as fully and efficiently as the technological side already is," he told the trustees in his report for 1898. Atherton blamed the paucity of undergraduates then enrolled in the nontechnical courses (about one-fifth of the student body) on the reputation Penn State had achieved in the technical fields which, gratifying as it was, nevertheless handicapped the College's attempts to attract students who did not wish to become engineers. "Many more [students] would be drawn here," he wrote "if the primarily technological character of our work did not obscure the extent of facilities offered in language, literature, history, philosophy, and other subjects of general education."

Unlike some college educators of that era, Atherton entertained no doubt that the Morrill Act mandated land-grant institutions to teach the liberal arts for their own sake, as well as for the purpose of giving engineering and scientific students a more balanced education. Atherton made a start toward upgrading liberal studies in 1896 by reinstituting the classical curriculum, with its core of ancient languages and literature, and introducing a new one in philosophy. The new curriculums drew no more than a half dozen students, however, so plans to add more nontechnical courses were delayed until 1903, when a course in modern languages and literature was initiated. According to the College catalog, this course was "designed primarily for those who are unable to take Latin and Greek and yet wish to pursue a thorough course in languages and literature as a preparation for teaching, journalism, law, the ministry, and like professions." It likewise attracted only a handful of students.

Credit for much of Penn State's growth during the early part of the Atherton era must go to the Pennsylvania legislature, which in 1887 began making a series of regular biennial appropriations to the College. Without the nearly $400,000 allocated by the Commonwealth between 1887 and 1893, construction of the Main Engineering Building, the Chemistry and Physics Building, and several smaller structures would have been impossible. Improved relations with Harrisburg came about mainly because the institution was at last offering the utilitarian instruction that many political leaders had been saying it must in order to prove itself worthy of public support. Another important factor in promoting harmony between Pennsylvania and its landgrant college was President Atherton's method of dealing with state officials. Atherton "thoroughly understood the sort of things that would impress the ordinary legislator," recalled Louis Reber, who explained that the president early on discovered that the lawmakers were "more likely to be impressed by what they could see than by what they could hear or read." Accordingly, Atherton arranged inspection trips to the College for interested politicians and was especially eager to have the visitors tour the engineering and science buildings, where they could observe the kind of practical education students received.

To further educate the lawmakers in the true work of the College, the President had Reber prepare a card index of all members of the legislature. On each card was written a legislator's name, a description of his political leanings, avocations, names of his friends, educational background, and similar personal information. Use of the index enabled Atherton to appeal on behalf of the College to legislators in ways that were most likely to yield positive results. In his quest for support from the Commonwealth, Atherton became the first president to enlist the energies of the alumni in any significant capacity. He and Reber made certain that each member of the General Assembly received periodic visits from prominent alumni residing in his district, who presented the legislator with publications from the College and brought him up to date on its current activities and plans for the future. In contrast to his authoritarian manner on the campus, George Atherton rarely used high-pressure tactics with Pennsylvania's elected officials. He knew that such methods would be useless, for since the Civil War political power in the state lay in the hands of a few bosses. Although as a political scientist he had detested oligarchy, Atherton was also a realist and made a special effort to cultivate close friendships with these leaders. His allegiance to the Republican Party-which by 1890 was the dominant force in Pennsylvania politics and would remain so for many years-did much to win the confidence of Donald Cameron, Matthew S. Quay, and other political chieftains.

Atherton's approach proved fruitful for a time as the College's appropriations rose steadily until peaking at $212,000 for 1895-97. Thereafter, enthusiasm for Penn State in Harrisburg waned. Atherton was at first inclined to be philosophical when he heard talk about future reductions in allocations to the College. "Every growing institution feels poor," he wrote. "The wider its field of work, the more numerous and the more urgent are its needs. Each new branch of instruction undertaken opens the door for many related subjects of equal or greater importance." The true dimensions of the problem became clear in July 1897, when the General Assembly allotted Penn State only $87,000 for the upcoming biennium. This action, which was to be matched over the next eight years by equally penurious outlays, at once puzzled and frustrated Atherton and all friends of the College. In view of the institution's demonstrated capability to graduate men and women who added measurably to the economic and cultural riches of Pennsylvania, how could any responsible lawmaker not realize that money invested in Penn State represented an investment in the future of the Commonwealth?

To some extent, the need to restore Pennsylvania's fiscal integrity dictated the actions of its lawmakers. By 1897, the state's failure to raise revenues to meet expenditures had created a $3 million floating debt that was rising by $500,000 annually. Given the unwillingness of the governor and the legislature to increase the government's income through higher taxes and other means, a policy of financial restraint was the only alternative. Nevertheless, the adoption of strict budget constraints only partially accounted for the Commonwealth's declining support for the College. In 1895, the legislature broadened its policy of aid to higher education to encompass more than highly specialized medical and scientific institutions and granted the University of Pennsylvania an allocation of $200,000. Two years later, when legislators were slashing Penn State's appropriation, they bestowed $150,000 on another private institution, Lehigh University. By virtue of their location in densely populated areas, many schools had a greater voice in the political arena than did Penn State, with its small constituency in rural central Pennsylvania, and thus could exert popular leverage of a magnitude that even the bosses could not ignore. Furthermore, the very existence of a political system controlled by a mere handful of individuals invited covert understandings between the bosses and a few influential supporters of private colleges and universities that resulted in actions favorable to these institutions.

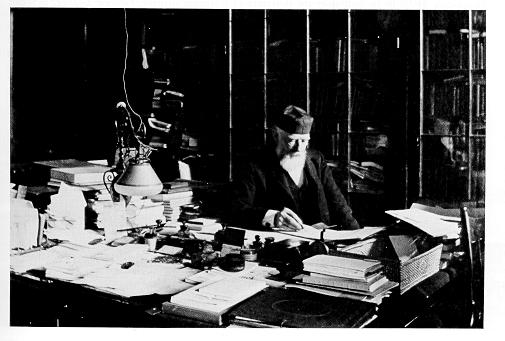

George Atherton at his desk in Old Main. He often work a skull cap—in private— to keep his bald head warm.

George Atherton never tried to undercut the efforts of other schools to obtain state subsidies, but he stoutly asserted that the Commonwealth owed its first obligation to its land-grant college. Only after that institution was adequately provided for did the claims of private colleges and universities have any legitimacy. To Atherton's dismay, many lawmakers and their constituents ignored the special ties that bound the College to the Commonwealth. They argued that Penn State had no privileged claim on the public treasury. Atherton countered by outlining on numerous occasions the nature of the relationship between the College and the Commonwealth. He admitted that the old Farmers' High School was chartered as a private institution and retained this status despite its acceptance of financial aid from the Pennsylvania legislature. Writing in his annual report for 1893 (a copy of which he made sure every legislator received), Atherton explained how Penn State's status changed after Pennsylvania designated it as the beneficiary of the land-grant endowment. "The state," he explained, "now made use of this private institution to fulfill a specific obligation to the general government, and this subsequent legislation brought the College into entirely new relations to the state, so that it is in law and in fact a state institution, which the state is under pledge to maintain and whose good or ill standing directly affects the credit of the state."

Atherton's explanations went unheeded. Appropriations for the College remained far below the amount needed to keep pace with the rapid growth of the student body. In desperation, the President tried to shame the Commonwealth into increasing its allocation for Penn State by having Louis Reber prepare a comparative study of other states' support of their land-grant institutions. Reber's report disclosed that Pennsylvania, the second richest state in the nation as measured by the assessed value of its property, ranked eleventh among forty-four states in total appropriations for land-grant education in 1897. At least thirty-five states-but not Pennsylvania-had enacted laws providing a fixed minimum appropriation for their land-grant schools. These minimums usually consisted of a certain percentage of the total tax revenues so that as the state grew, so did the aid to the land-grant institution. Wisconsin, a leader in legislation of this type, at one time set its rate at 17 over 40 of a mil, the highest in the nation. Wisconsin and other states' had realized, after the initial decade or so of confusion surrounding the passage of the Morrill Act, that the endowment it created was never intended to be a college's primary source of income. In Pennsylvania, no one knew from one legislative session to the next how much money Penn State would receive, a situation that made planning for the future extremely difficult.

The College also ranked low in the size of its land-grant endowment, thanks to the injudicious land sales of the 1860s. It received $30,000 annually from the original grant of 780,000 acres. Reber discovered that at least thirty states disposed of their land to better advantage. Kansas, for instance, obtained $50,000 annually for its land-grant institution from just 90,000 acres, Michigan $31,000 from 240,000 acres, and Minnesota $27,000 from 120,000 acres. In 1890 Congress had passed the second Morrill Act, boosting yearly incomes of land-grant institutions by an eventual $25,000; but Reber and Atherton viewed that legislation as an indication that the federal government agreed that too many states gave their land-grant schools inadequate support. The findings of Reber's report had little effect on the General Assembly, which voted to give Penn State only $67,000 for 1899-1901. Governor William A. Stone, exercising his power of item veto, further trimmed this amount to $55,000, or one-fourth of what the College had received four years earlier.

On at least one occasion the students themselves may have contributed to the troubled relations between the College and state political leaders. The General Assembly's Joint appropriations committee periodically visited the campus to see what the institution needed and how it was spending its money. The committee customarily arrived by a special railroad car, well stocked with food and drink, that was parked near the Bellefonte Central station while the lawmakers conducted their inspection. Fred Lewis Pattee, who Joined the faculty in 1894 as a professor of English, wrote that during one such visit, the "hell-raising element" of the student body raided the car. After overpowering the cook and porter, the students assaulted the icebox, "leaving not a drop of that benign fluid so necessary for legislators," and making off with what they could not eat or drink on the spot.

Ironically, it was not the pleading of the College itself, but rather the lobbying of an interest group, that finally won an increase in appropriations for Penn State. In 1903, the Allied Agricultural Organizations of Pennsylvania-a loose-knit group of sixteen state agricultural associations that was founded in 1900-prevailed upon the legislature and the governor to approve $100,000 for a badly needed dairy building (Patterson Building), which was completed in 1904. Penn State received an even larger sum from the Commonwealth in 1907 to underwrite the cost of a new Main Agricultural Building (Armsby Building). To pay for the other structures it required, the College had to look elsewhere for funds. It used general funds to construct two single-story, barracks-like temporary dormitories-nicknamed Bright Angel and Devil's Den-in 1903-4 and the following year borrowed nearly $100,000 to finance a permanent dormitory and dining facility, McAllister Hall. The College could stretch its meager resources only so far, of course. Had not two of its most illustrious trustees come to its rescue at this time, the institution would have faced a grave crisis with regard to its physical plant.

In 1899, Andrew Carnegie, founder and head of the nation's largest steel company, offered to donate $100,000 for the construction of a new library on the condition that the Commonwealth provide $10,000 annually for its upkeep. Carnegie understood the College's plight, having represented state industrial interests on the board of trustees since 1886. Ignoring the appeals of Carnegie's fellow trustees and President Atherton, who as early as 1894 had remarked that "the greatest need of the College today is a library building, arranged with reading rooms and departmental libraries and with a means for regular growth," the General Assembly refused to guarantee the money. Eventually the trustees themselves pledged to supply a yearly sum adequate to maintain the library, after which Carnegie gave $150,000 for a new library building. It was completed in 1904 and named after its benefactor.

Farmers line up to deliver milk to the College creamery (later Patterson Building). The creamery sold most of its products in the State College and Altoona retail markets.

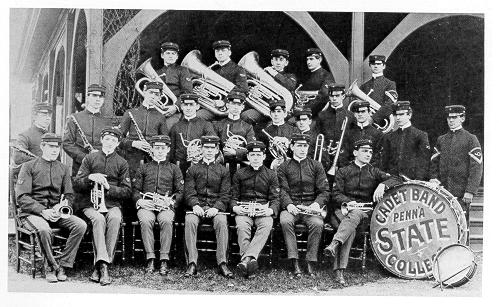

This was not Carnegie's first act of generosity toward the College. Several years earlier, the students had asked Atherton for money to purchase instruments for a brass band to accompany the cadet military battalion. The request was denied, since there was no money for anything but absolute necessities. Professor A. Howry Espenshade of the English department then called on President Atherton with a suggestion. "Andrew Carnegie has a great fondness for donating organs," said Espenshade, "and I believe that he might perhaps be prevailed upon to buy the necessary instruments for a cadet band for our student battalion." "Well, there would certainly be no harm in asking him," replied the president, who directed Espenshade to draft a letter requesting $100, to be sent over the signature of Carnegie's friend, General Beaver. A week later Carnegie sent back a check for $800, along with a note of explanation. "I take pleasure in making this gift," the steel magnate wrote, "because I have long held that there is no better way for a boy to get the devilment out of his system than to blow it out through a brass horn."

Charles M. Schwab, an associate of Carnegie's both on the board of trustees and in the steel industry, agreed in 1902 to give $150,000 for a new auditorium to replace the antiquated and overcrowded chapel of Old Main. Fred Pattee, who became a close friend of President Atherton, recalled in his memoirs that the vision of what was to become Schwab Auditorium "from the first stirred the soul of Dr. Atherton as nothing else had during his administration." The president regarded the auditorium as the architectural showpiece of the College, and insisted that it be completed in time for commencement in June 1903. As the winter of 1902-3 approached, he ordered the unfinished structure to be encased in a huge wooden shell and provided with heat and light so that work would not be interrupted by the cold and snow. When bricklayers walked off the job to protest the use of non-union labor, Atherton fired them and hired non-union masons to keep the project on schedule. Only finishing touches remained to be applied when the graduating class of 1903 assembled in the new auditorium to receive their diplomas.

THE IMPRINT OF FACULTY, STUDENTS, AND ALUMNI

The College could not rely on the benevolence of its trustees to help obtain the additional faculty and instructional resources it needed. Between 1895 and 1905, Penn State experienced its most difficult era, financially speaking, since the time of President Calder. In some ways the institution was even more hard pressed around the turn of the century than it had ever been. Enrollment was rising rapidly, whereas the student population had previously decreased in times of fiscal adversity. Undergraduate enrollment rose from 232 to 680 during the decade following 1895, yet the teaching staff increased from 44 to only 59. Class size swelled until many freshman and sophomore classes numbered 40 students or more-a small group by later standards but unwieldy under the pedagogical conditions of the turn of the century and larger than those found at many comparable institutions. Laboratories, especially, suffered from overcrowding. Because little money was available for the purchase of new equipment, much of the laboratory hardware, the most modern available when originally installed, was fast becoming outmoded in an age of rapid technological advance. As in the past, the College was able to secure some equipment at reduced cost from industrial sources. The electric railway, for instance, was for the most part a home-built affair, assembled by the electrical engineering students and faculty from begged and borrowed materials. In too many cases, however, students had to make do with laboratory gear that was out of date and insufficient to serve large classes.

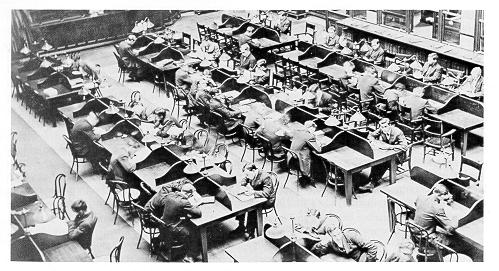

Reading tables in Carnegie Library, about 1908.

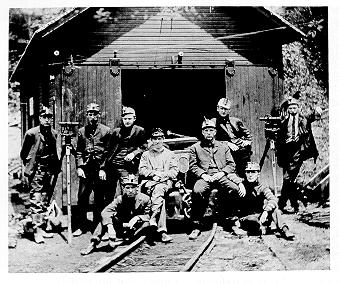

The major casualty of the financial crisis was the School of Mines. Lacking a home of its own, it initially shared space in the Main Engineering Building. Cramped quarters there prevented Dean Magnus Ihlseng and the four other members of the School's teaching staff from developing the kind of mining curriculums needed by a state so blessed with mineral wealth as Pennsylvania. But strong prejudice in the mining industry against academically trained engineers left the Commonwealth's mining interests indifferent to the possibility of lobbying for increased support of collegiate programs in mineral education. Furthermore, the legislature had already allotted $50,000 to the Western University of Pennsylvania to establish a school of mines and showed little inclination to give lhlseng the amount of money he required to upgrade work in mining engineering and related areas. The state appropriation for the College's School of Mines for 1899-1901 was so miniscule that it was inadequate to sustain even the modest curriculum then in existence. In 1900 President Atherton and the trustees reluctantly abolished the school, replacing it with a new Department of Mining Engineering within the School of Engineering. Ihlseng, whom Atherton had personally recruited from a professorship at the Colorado School of Mines, resigned in disgust.

Under the direction of his successor, Marshman E. Wadsworth, former president of the Michigan College of Mines and a topflight administrator, the department underwent reorganization. Aided by a donation of $5,000 from Andrew Carnegie, the old Mechanic Arts Building was moved west along College Avenue to a point beyond the railroad station. Slightly larger state allocations than those received earlier allowed the department to make a small addition to the building and to add assaying, metallurgical, and mining laboratories. These improvements reversed the decline in the enrollment so that by 1906, 97 undergraduates were in attendance, making the department the largest in Pennsylvania and the fifth largest in the nation. That same year the trustees approved Wadsworth's request to reestablish an independent School of Mines and Metallurgy, which offered options of study in mining, mineralogy, geology, and metallurgy. The legislature reinforced this measure with an appropriation of $20,000 in 1907 for another enlargement of the mining building, and the school's future as an independent body was assured.

Because of the College's impoverishment, faculty salaries in all seven schools were low. Inadequate compensation and heavy class loads caused a high turnover among teachers, particularly in the engineering departments, where a professor typically earned an annual salary of $1,500, or approximately one-third of what he could make in private industry. Only about half of the College faculty of 1895-96 were still at Penn State five years later. Many teachers also had no liking for the institution's geographic isolation and, after acquiring a few years' experience, departed for more remunerative positions nearer large cities.

Cadet Band, antecedent of the Blue Band, in 1902, with instruments paid for in part by Andrew Carnegie.

The dedication and perseverance of the faculty who remained left an indelible impression on hundreds of students. Perhaps the most legendary figure on the teaching staff was George G.

Pond, dean of the School of Natural Science. Pond, like his fellow deans, continued to teach in addition to fulfilling his administrative responsibilities. His gruffness of manner and passion for excellence invariably aroused terror in his students. They responded by making "Swampy" Pond the perennial target of some good-natured satire in La Vie and other publications. From Froth, one of the College's humor magazines, came this story:

The State College candidates for a harp were standing before Saint Peter.

"Who did you have in chemistry while at college?"

"Pritchard," answered the first.