By the early 1970s, the age of affluence for higher education had ended. Social, economic, and demographic changes were causing educators to question the validity of the assumptions that had guided them for more than a decade, namely, that an ever-expanding economy would provide limitless resources for colleges and universities, that the proportion of high-school graduates entering college would continue to rise, and that a baccalaureate degree was essential to securing a high-paying, personally satisfying job. Penn State and other institutions were forced to begin adjusting to the unpleasant realities of a new era-realities such as a declining birthrate, cutbacks in public funds, and an oversupply of graduates in many fields. At the same time, this new era offered the University new opportunities for carrying out its historical mission of teaching, research, and public service.

A Decade of Change

The rate of expansion at Penn State slowed, but growth did not stop. Total full-time enrollment on all campuses climbed from 35,764 in 1969-70 to 49,360 in 1973-74, as Penn State rose from the thirteenth to the eleventh largest institution of higher education in the country. At University Park, millions of dollars continued to be spent for new buildings, including the Milton S. Eisenhower Auditorium, the Liberal Arts Tower, the Agricultural Administration Building, the Museum of Art, and major additions to the HUB. No new Commonwealth Campuses were begun, but existing facilities were upgraded. More prominent than growth during the 1970s, however, were the important changes that occurred at almost every level of the institution, from the board of trustees on down.

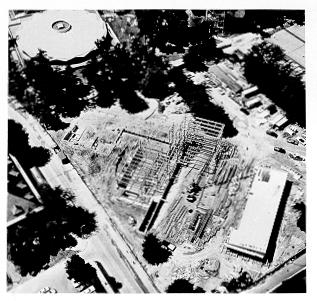

The pace of building construction at University Park in the early 1970s was still vigorous, as evidenced by this view of the unfinished Museum of Art.

The trustees had taken an active part in shaping the course of the University during its first twenty-five years of life. After George Atherton assumed the presidency there was less need for direct trustee involvement, and the board as a whole receded into the background. The trustees' executive committee continued to work closely with the University president in matters of fundamental policy; the full board, meeting only twice a year, in most instances merely ratified decisions that had already been made. This manner of operation continued without substantial alteration into the 1960s. It was neither democratic nor easily accessible to public scrutiny, but it was effective, and the institution was nearly always well served by a competent, if somewhat cliquish, executive committee. Moreover, the corporate leaders and agriculturalists who normally comprised that committee were accustomed to conducting their own business in private and saw nothing sinister about handling University affairs in the same way. Penn State was, after all, in the legal sense a private corporation, not a department of the state government.

The full board became more active again beginning in 1970 with the election of G. Albert Shoemaker to the board presidency. Former head of Consolidation Coal Company, Shoemaker succeeded Roger Rowland, who had stepped down after seven years, service as board president. Trustees not privileged to be part of the inner circle had for some time been asking for a greater voice in decision making, and Shoemaker took steps to insure that these wishes were satisfied. "I strongly feel the responsibility of having the entire board more fully informed of the University's activities," he remarked at the opening of a trustees' meeting in September 1971. "Enlightened action based on complete information will certainly be wiser action when it becomes the responsibility of the entire board." One of the most important innovations in bringing about more participation by all trustees was to increase the frequency of regular meetings to seven (later six) times a year. Another was to schedule meetings periodically at the branch campuses, in order to get a broader view of the University's sphere of operations. Shoemaker's successors-Michael Baker, Jr. '36 (1973-76), founder and president of an international engineering consulting firm; William K. Ulerich '31 (1976-79), Pennsylvania newspaper and radio executive; Quentin E. Wood '48 (1979-82), chairman of the board of Quaker State Oil Refining Corporation; Walter J. Conti '52 (1982-85), well-known Doylestown restaurateur; and Obie Snider '50 (1985- ), Bedford County dairyman and Master Farmer-continued the policy of giving all trustees a chance to participate in board affairs.

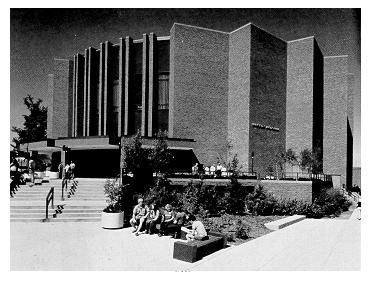

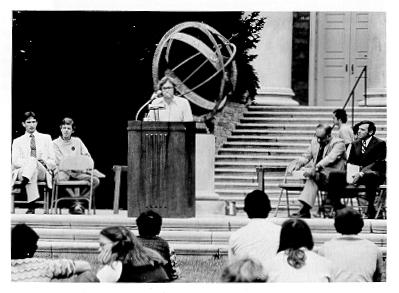

University Auditorium (renamed Milton S. Eisenhower Auditorium in 1977) replaced Schwab Auditorium as the site for larger cultural and educational gatherings.

Two more changes in the board resulted, at least in part, from external initiatives. First, Governor Milton J. Shapp, true to a promise he made during his gubernatorial campaign in 1970, appointed a student to the board in 1971, thus beginning the custom of having one of the governor's six appointments reserved for a representative of the student body. Undergraduate Student Government president Benson M. Lichtig was one of several students Shapp named to the boards of the state-related universities.

Another change emanated from Harrisburg in 1974, when the General Assembly passed a "Sunshine Law" that mandated governmental bodies of all sorts to open their general meetings to the public. Some trustees questioned whether the law applied to the University-its legal status, as usual, could be interpreted in various ways-and warned that public meetings would become circuses and drive business back into the executive committee. The majority of the trustees, including President Michael Baker, had no such apprehensions and decided not to contest the issue. Some trustees wanted to make the meetings of the board's committees accessible to the public, pointing out that most of the actual work was done in committee and that Pennsylvania taxpayers had a right to know how the University decided to spend their money. (The number of standing committees had recently been reduced from nine to three educational policy, physical plant, and finance-in an effort to streamline operations.)

Architectural rendering of Pattee Library's east wing, complete in 1973.

Whether committees should continue to convene behind closed doors was a matter of debate among the trustees for nearly two years, with Baker and his successor William Ulerich both favoring public meetings. The issue was finally decided in September 1976, when by a 14 to 13 vote the board decreed that the public would be permitted to attend all regular meetings of the board's standing committees. Sunshine legislation did not bring about the profound changes people hoped-or feared-it would. Ordinary citizens had the opportunity to view all formal trustee sessions, and the actions of the board were duly reported by the news media.

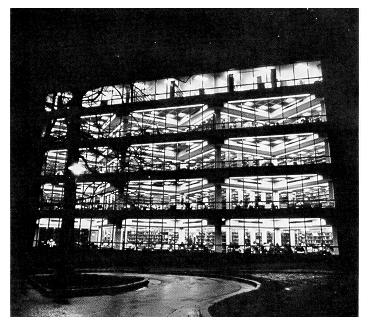

Normal closing hour at Pattee: midnight.

Change also came to the University presidency. In January 1969, Eric Walker announced his retirement, to take effect June 30, 1970, two months after his sixtieth birthday. Walker had always maintained a presence in governmental and scientific circles-he had been instrumental in founding the National Academy of Engineering-and he wanted to leave Penn State while he still had time to have a career outside academia. He had originally intended to depart in 1966, but the trustees convinced him to stay; this time he was determined to leave.

Contrary to a notion that began to circulate in later years, student unrest played little or no part in his decision to step down. Indeed the worst of the disorder did not occur until after he had made his resignation public. After leaving the University, Walker became vice president of science and technology for the Aluminum Company of America, headquartered in Pittsburgh. He helped to make Alcoa's research program the most extensive in the light metals industry by the time he retired from the firm's management in 1975. (He remained a member of Alcoa's board of directors, as well as president emeritus and professor of engineering emeritus at Penn State.)

The trustees had broken with precedent when they named Walker president of the University with little or no consideration of other candidates and so soon after Milton Eisenhower had made known his intention to depart. In selecting Walker's successor, the trustees returned to tradition, launching a nationwide search and carefully assessing dozens of candidates. The board did depart from past practice in one respect by agreeing to consider candidates chosen by a special panel of seven faculty senators and four students. These candidates were to receive no more preference than those submitted by the trustees' own search committee, although in the end the next president was among the three finalists recommended by the faculty-student committee.

He was John Wieland Oswald, 52-year-old executive vice president of the University of California system. The first agriculturalist to head Penn State since Evan Pugh, Oswald was born in Minnesota, spent his boyhood in Illinois, and majored in botany at Indiana's DePauw University. He undertook advanced studies in plant pathology at the University of California's Davis campus and received his Ph.D. in 1942, Just in time to begin active duty with the Navy. During much of World War II, Oswald was stationed in the Mediterranean in command of a squadron of PT boats. He returned to Davis after the war to teach and conduct research on plant diseases. After being named head of his department in the mid-1950s, he transferred to the Berkeley campus and gradually exchanged his faculty duties for administrative responsibilities. By 1962, he had become vice president of administration for the University of California and a confidant of its president, Clark Kerr.

But Oswald desired more independence and in 1963 accepted the presidency of the University of Kentucky. His tenure at that institution was in many ways similar to Eric Walker's at Penn State. Oswald was instrumental in developing the 15-campus University of Kentucky community college system and won substantial increases in state appropriations. Enrollment rose by 50 percent in five years (to 14,500), the physical plant was upgraded, and special efforts were made to improve the quality of research and graduate studies.

The University of Kentucky was not immune to student unrest. President Oswald stated that while he did not share some of the views of campus dissidents, he would defend their right to express their opinions. This stance in favor of academic freedom made him unpopular with important state political figures, who took a less tolerant attitude toward student protesters. In addition, attempts to politicize certain operations of the institution seemed certain to intensify after the election of a new and more hostile governor in 1967. When in 1968 he was offered the executive vice presidency of the University of California, Oswald resigned and returned to Berkeley.

Penn State's trustees formally selected John Oswald as the University's thirteenth president in December 1969, and he took office on July 1, 1970. Adhering to a grueling agenda his first year, he spent most of his time trying to improve relations between students and administration, overseeing the preparation of a development plan for the 1970s, becoming acquainted with the Commonwealth Campuses, familiarizing himself with the intricacies of Pennsylvania politics, and attempting to restore harmony between the University and the state's other institutions of higher education.

Attending to these tasks and more left Oswald mentally and physically exhausted. On June 16, 1971, he suffered a heart attack. Paul Althouse, Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost (a newly revived title) assumed many of Oswald's duties while the president underwent treatment at the Hershey Medical Center. By September, Oswald had recovered sufficiently to resume work on a limited basis, and within a few months he was handling a full schedule again-though not at so frenetic a pace as before.

At the faculty level, teachers and researchers pondered the wisdom of changing their relationship to the administration through the adoption of collective bargaining. Faculty manifested considerable dissatisfaction during the 1970s on two points. One was President Oswald's alleged tendency to deputize authority far more than his predecessors and in doing so build an unwieldy administrative bureaucracy. (The number of vice presidents rose from eight in 1970 to twelve in 1973; the number of academic divisions increased from thirty-five to forty-four.)

As he became more dependent on the advice and counsel of his administrative staff, critics said, he involved the faculty less in the governance of the University. The second issue involved compensation. The cost of living rose at a rate that surpassed even that of the post-World War II era, and the University found it could not maintain salaries and benefits that allowed its employees to keep pace with inflation, let alone get ahead of it.

Some faculty saw a solution to both of these problems in unionization. Collective bargaining at institutions of higher education began on a large scale nationwide in the late 1960s. The trend started in Pennsylvania shortly after the legislature, in 1970, passed a law granting all state employees and those at state-related institutions the right to bargain collectively. By the end of the decade, most of the Commonwealth's community colleges, the state colleges and university, and Temple University had faculty unions (the American Association of University Professors at Temple, the National Education Association and Pennsylvania State Education Association at the other schools).

The drive to win collective bargaining rights for the Penn State faculty began in 1971, when some members of the teaching staff at the Commonwealth Campuses formed PSU-BRANCH and affiliated with the Pennsylvania State Education Association and the National Education Association. Many Commonwealth Campus faculty believed that their departments and administrators at University Park did not fully appreciate the unique circumstances and purpose of the branches. They complained that they often carried heavier teaching loads and had fewer scholarly resources at their immediate disposal but were expected to meet the same research and publications requirements for tenure as their colleagues at the main campus. The Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board refused to authorize an election to determine whether PSU-BRANCH would be the bargaining agent because the organization did not include personnel at University Park and therefore did not constitute an appropriate bargaining unit. Organizing activities then started at the main campus. Two groups vied for the right to represent the faculty at all the campuses (except Hershey): the Pennsylvania State University Professional Association (PSUPA), which superseded PSU-BRANCH as the PSEA/NEA affiliate; and the Penn State chapter of the American Association of University Professors.

First open meeting of the Board of Trustees, Keller Building, Sept. 20 1974.

The PLRB set March 30 and 31, 1977, as the date for an election to determine which, if either, would be the bargaining agent. President Oswald informed the faculty (teachers, researchers, and librarians mainly) that in his opinion a faculty union would replace the collegial approach to governing the University with an adversarial relationship. Adherents of PSUPA and the AAUP contended that a union would force the administration to take the faculty viewpoint into account when making important policy decisions or high-level administrative appointments and lead to better salaries and working conditions.

Ninety-three percent of the faculty voted. PSUPA, which ran the more vigorous campaign and was backed by a heavy infusion of PSEA/NEA funds, received 642 votes, the AAUP 500, and no representation 1,712. The balloting ran counter to a national trend. At the time of the election, faculty at 366 colleges and universities had consented to establish collective bargaining. At only 74 institutions did the faculty choose to have no representation.

The most noticeable changes at Penn State in the 1970s occurred among the students. President Oswald gave top priority early in his tenure to student affairs. He was worried that too many students felt alienated from the University and society, largely because adults failed to listen to what the younger generation had to say. He announced his intention to make communication between students and administrators a two-way process.

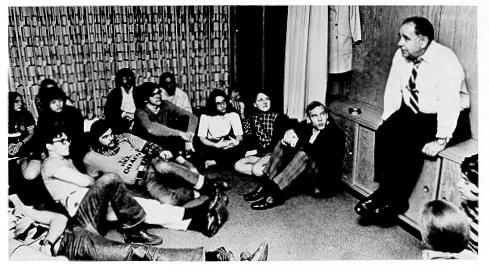

The President began a series of "rap sessions" with undergraduates, spending as many as three evenings a week in informal discussions in residence halls or at the Hetzel Union Building. He occasionally took his meals in the dining halls and at least once stayed overnight in a dormitory. The students were generally pleased with Oswald's interest in them and with the responses he gave to their questions. When asked during one session why the University did not have its own bookstore, for example, Oswald replied, "That's the same thing I asked when I came here," and said he was already looking into the matter. Answering complaints about the long waits, unavailability of emergency treatment, and allegedly callous attitude of personnel at the Ritenour Health Center, Oswald admitted that "a genuine problem" existed there and promised to remedy the situation as best he could. Once he was asked how he would deal with campus demonstrators who demanded to meet with him. "If I felt a group [of students] was marching somewhere to talk to me," he declared, "I would try to let them find me as quickly as possible so we could debate the issue before we get a lot of unnecessary trouble."

None of the president's actions was more popular among student activists than his removal of Charles Lewis as Vice President for Student Affairs. (Replacing Lewis was Raymond O. Murphy, former head of the Division of Campus Student Affairs, a position that incorporated much of the work of the deans of men and women after those posts were abolished in 1968.) Oswald also helped to convince the trustees to authorize a University-owned bookstore, which opened in 1973 and steadily expanded its merchandise lines and services over the next decade. It was not the kind of cooperative store that students had been talking about since the 1940s, but the venture was successful enough to provoke complaints from State College merchants about unfair competition.

Students initially found the president's style refreshing and affectionately referred to him as "Jack the Rapper" or "the Big O." The more conservative members of the board of trustees, by contrast, believed Oswald had been too zealous in his attention to students. In oftentimes heated discussions on this topic, they argued that late-night dorm meetings and question-and-answer sessions in the HUB were nonproductive and took too much time away from more traditional presidential activities. Board president Shoemaker was especially insistent that Oswald was devoting time to student affairs that could be used to better advantage elsewhere. Ironically, many of the disgruntled trustees were the same ones who in June 1970 had voted to give the president's office more authority over student matters. Unhappy with the liberal outlook of the University Senate, and especially perturbed by the Senate's approval of twenty-four hour residence hall visitation, the board had transferred to the president many of the housekeeping chores associated with student operations as part of the general reorganization of the Senate that year.

Oswald also had to deal with protests spawned by antiwar sentiment, although the conflict in Vietnam was slowly winding down. President Nixon's so-called Cambodian invasion in the spring of 1972 provoked the largest demonstration. On May 10, 2,000 students rallied on the lawn of Old Main before sweeping into the streets of downtown State College, sealing off the business district for the rest of the day. State police were alerted, but for the most part the confrontation remained free of violence. The next day, a thousand protesters converged on the Ordnance Research Laboratory. After consulting Lieutenant Governor Ernest Kline, who was on the scene as the governor's personal representative, Milton Shapp ordered the laboratory closed for the next several days to prevent further disruption. Believing Shapp had overreacted, President Oswald chose to meet with leaders of the protest and promised a review of the University's policy on military research.

"Jack the Rapper"

The administration reviewed its military research policies but saw no reason to implement any major modifications. In January 1973, the board of trustees did vote to rename the Ordnance Research Laboratory the Applied Research Laboratory to show that the facility did more than develop top-secret naval weaponry. According to an announcement made at that time by Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies Richard Cunningham, only 25 percent of the laboratory's work (mostly relating to torpedoes and underwater missiles) was of exclusive interest to the Navy. The remainder had important civilian applications in acoustics and other fields and was widely disseminated in technical journals. Nearly a dozen graduate students every year earned degrees using the laboratory's resources.

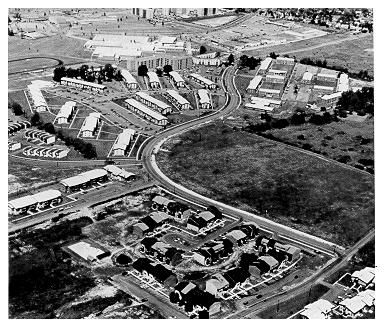

What the typical student cared about far more than what kind of research the ORL was performing were the exigencies of everyday life at the University. With no new residence halls being built and enrollment still rising, more students had to utilize off-campus housing. (Only freshmen of both sexes were required to live in the dormitories.) The cost and quality of that housing became issues of great concern. Although new apartment complexes appeared yearly, the market still favored the landlord. Students complained bitterly about high rents, poor maintenance, safety and health hazards, and unreturned security deposits, while landlords pointed to the high incidence of student vandalism, rising utility and tax bills, and other costs of doing business that made rents generally higher than anywhere in the Commonwealth outside Philadelphia. The Organization of Town Independent Students (OTIS) was founded in 1970 to replace the Town Independent Men as the collective voice for students living off campus, but its effectiveness in improving the lot of its constituents was limited. What could it or any other student organization do when demand so far outweighed supply that prospective tenants, had to sign leases in February or March for the following academic year in order to make certain of getting satisfactory apartments? And woe to the unknowing transfer or foreign student who arrived in State College a few weeks before classes began in the fall and expected to find decent, affordable housing.

Student apartment complexes dominate both sides of Waupelani Drive in this 1970 view of southwest State College.

Penn State students also had a number of academic concerns, most of which they shared with their counterparts at other large state universities. They complained that many classes were too large and professors seemed more interested in doing research than teaching undergraduates. Inexperienced graduate teaching assistants, they contended, frequently taught smaller classes. One of the most familiar grievances of undergraduates at University Park was that faculty advisers were often uninterested and unskilled in helping their advisees work their way through the complexities of the academic bureaucracy.

The 1970s witnessed a significant transformation in the academic interests of students. With sluggish state and national economies making good jobs harder to find than anytime since the 1930s, more students were entering fields that had the best employment prospects. In general, science, engineering, and business administration flourished, while the humanities and teacher education went into relative decline. Many small liberal arts and teachers colleges found themselves implementing new curriculums in fields as diverse as marketing, health administration, and law enforcement in order to attract students. At land-grant institutions, with their traditional emphasis on utilitarian education and low cost, overall enrollments remained steady or continued to increase gradually. Capitalizing on its strengths in engineering, earth and mineral sciences, and business administration, Penn State (although it could no longer boast of having a low tuition rate) remained the nation's ninth largest institution of higher education in 1981, with a full-time enrollment of 51,894 students.

Accompanying the shifts in students' academic preferences was a change in their attitudes and values. Hat societies, freshman customs, and other symbols of the 1950s may have disappeared in the turbulence of the activist era, but some observers professed to see in students in the late 1970s and 1980s the same passiveness, lack of idealism, and preoccupation with material gains that supposedly were the hallmarks of the "silent generation." There was at least one important difference, however. Inbred with a cynicism that was perhaps a legacy of the Vietnam protests, leaders of the newer generation did not display the same kind of trust in or acceptance of authority that students had twenty years earlier.

Students were gradually assuming a greater voice in the University's official decision-making processes. One of their number sat on the board of trustees. A reorganization of the University Senate in 1971 gave them 14 of 144 seats. Four of the twelve members of the University Council, created at the end of the Walker administration to keep the president abreast of campus developments, were students. The newly formed Student Advisory Board was designed to serve the same purpose.

But many students claimed that this was token representation and that administrators were still not sufficiently receptive to their needs and problems. To them, John Oswald came to symbolize an administration that too often did as it pleased, without consulting the student body. Now that antiwar protests were on the wane, his critics said, the president was no longer interested in continuing his dialogue with students. Some of the earliest and most pungent criticism came in a March 3, 1972, Daily Collegian editorial subtitled "Whatever Happened to Jack the Rapper?" The Collegian editors noted that "the atmosphere on campus, particularly among those students who had to deal with the administration, was brightened considerably" by Oswald's early initiatives. He had to lighten his work load while he recuperated from his heart attack; but now that he had regained his health, why had he not resumed his frequent consultations with students? "Students are now little better off than they were under the Eric Walker administration," the editors affirmed. "Very little consultation is going on. It is hard to escape the conclusion that Oswald has not restarted the rap sessions because he realizes by now that ignoring the students will probably not cause them to rise in violent revolt." Similar criticism came from leaders of various undergraduate organizations and was to hound Oswald for the rest of his tenure.

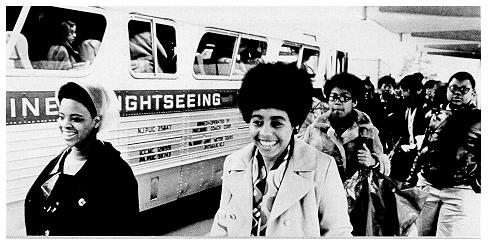

As part of its efforts to enroll more blacks, the University hosted groups of black high-school students for campus orientation.

Besides changes in student attitudes and interests, important changes also took place during the 1970s in the very composition of the student body. In the fall of 1970, approximately 1,300 blacks (about 3 percent of the total student population) were in attendance. This figure represented marked improvement over previous years, but the newly arrived John Oswald was dismayed to find that so many black students were doing less than satisfactory academic work. "It was my judgment," he recalled, "that we had blacks here for the sake of blacks, for the purpose of counting. This was a disservice to the black community." He acknowledged that Penn State should do its utmost to recruit black students, but it should "recruit for commencement," not merely to meet some mathematical goal without regard to what happened to the students after they enrolled. Oswald centralized the University's efforts aimed at increasing the black student population into a new Educational Opportunity Program. Through the EOP the institution provided tutoring, counseling, and special summer transitional activities for black students who showed academic promise but who were inadmissable under ordinary scholastic standards and lacked the financial resources for a college education. Several hundred EOP students were admitted each year.

By the mid-1970s, after the EOP had been expanded to include students of all races and the University had begun to put more emphasis on the academic potential of these recruits, the number of black students began to decline. The Oswald administration was subject to charges from leaders of the black community and others that it was insincere in its efforts to attract racial minorities to Penn State. The federal government, through the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, also expressed its dissatisfaction with the small percentage of blacks at the University, not only as students but in the faculty and staff ranks as well. The administration redoubled its efforts to increase black enrollment by adding more black recruiters, affirmative action coordinators, a minority affairs director, and a Black Scholars Program. The board of trustees set up its own committee on affirmative action. But progress was painfully slow and by the early 1980s, the number of blacks in attendance was only slightly higher than it had been a decade earlier.

The University was also criticized internally and externally for its neglect of another segment of the population-women. The scarcity of women at Penn State had for decades given rise to discontent among students and alumni, and it was not the kind of distress felt by males who despaired of getting weekend dates. An institution supported so heavily by public funds, many persons said, should afford equal opportunities to both sexes. The emergence of the women's rights movement in the 1960s and the passage of federal equal opportunity laws put additional pressure on Penn State to reexamine its admissions and employment practices. Since the 1950s, the University had used a ratio of about 2.5:1 as a guideline in admitting men and women to the University Park Campus. (Students were admitted to the Commonwealth Campuses without regard to gender.) This practice had brought the threat of lawsuits from both the public domain and the government. In the spring of 1971, after consulting with the trustees and the University Senate, President Oswald announced that the University would begin to accept students at all campuses without consideration of sex by the fall of 1972. He also directed colleges and departments encompassing disciplines traditionally dominated by males to make special efforts to recruit more women.

In addition to the moral and legal implications of sexual discrimination, there was no longer any practical reason to restrict the number of women students. The University had only to guarantee sufficient residence hall accommodations for freshmen. By 1975, the male-female undergraduate ratio at University Park had fallen to approximately 1.5:1. Revised admissions policies were only partly responsible for this change, which also stemmed from new social attitudes toward higher education for women, especially in the scientific and technical fields.

The University made less satisfying progress in its attempts to hire more female teachers and researchers. Nearly every college and university in America was seeking more women-along with more blacks and other racial minorities-for their faculties. A sufficient supply of qualified personnel to meet this demand simply did not exist in many fields.

Increased sensitivity to equality of gender even brought about changes in the Alma Mater, the words to which had been written by Fred Pattee in 1901 and were sung to the tune of the hymn, "Lead Me On." "When we stood at boyhood's gate," went the third verse, "shapeless in the hands of fate, thou didst mold us dear old State, into men." In 1975, by official University action, "boyhood's gate" became "childhood's gate," and "into men" was dropped in favor of repeating "dear old State."

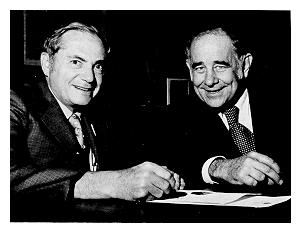

Milton Shapp (left) and John Oswald

Financial Stress

The single most dominant theme in the University's history during the 1970s was the struggle to maintain an income adequate to the institution's needs. Unyielding inflation and a gradual decline in the state's economy lessened the will and ability of the Commonwealth to provide support for higher education, thus placing Penn State in the most precarious financial position it had been in since the 1920s.

Because of the magnitude of the appropriations Penn State was receiving and the state government's own financial insecurities, political leaders subjected the University to closer scrutiny and more criticism than it had received since the nineteenth century. Meeting in public and private with legislators every winter and spring to discuss the upcoming budget, President Oswald and his subordinates were hit with a barrage of questions seldom, if ever, asked of their predecessors. Was Penn State not top-heavy with administrators? Could not the University save money by reducing its large fleet of automobiles? Did it really need to own more than one airplane, if even that? And was it true that Penn State leaned so heavily on graduate teaching assistants-many of whom were alleged to be foreign students having only a passing acquaintance with the English language-because so many of its faculty were preoccupied with research? Even agriculture, almost sacrosanct where the General Assembly was concerned, came under fire. Some legislators contended that the activities of the College of Agriculture benefited mainly large commercial enterprises and worked to the detriment of the family farm, which was supposed to constitute the backbone of Pennsylvania agriculture.

Penn State was not the only target of sharp questioning. Most legislators took a genuine interest in making certain that tax dollars were spent as wisely as possible at all of the state-owned and state-related institutions. In 1972 the General Assembly amended its higher education appropriations bills to include a requirement that institutions submit information on the number of hours faculty spent in various scholarly endeavors, how many students were enrolled, how many degrees were awarded, and other statistical data that were intended to indicate a measure of academic productivity. Educators unanimously rejected the validity of the exercise, but the legislature made submission of such information an annual requirement. It was compiled and published in a document popularly known as the Snyder Report, after the sponsor of the original amendment, Lancaster County senator Richard A. Snyder.

In dealing with the state government on budgetary matters, Penn State officials also had to work with the new Department of Education, a reorganized and more powerful version of the old Department of Public Instruction. Hostility toward the University left over from the Commonwealth Campus controversies was still evident in the early 1970s, and departmental authorities continued to regard Penn State as an octopus, an opinion shared by leaders of many other institutions of higher learning in the state.

President Oswald went to great lengths to try to eradicate what he termed the "octopus syndrome." In place of unilateral action, he preferred to have the University make decisions in consultation with the Department of Education and the Pennsylvania Association of Colleges and Universities. Thus no new Commonwealth Campuses were established, and although development of the new Allentown Campus site finally got under way, even that action had conciliatory overtones. Through an informal agreement with other schools in the area, Penn State phased out associate degree instruction at Allentown and restricted itself to a two-year undergraduate curriculum (with a limit on enrollment) and continuing education activities. Plans to have more campuses (McKeesport and Hazleton were the most likely candidates) follow Behrend's lead and become semiautonomous four-year schools were set aside, as was yet another proposal for a law school. Many friends of the University believed that Oswald had gone too far in these and other measures to placate Penn State's foes and rivals. Other observers, particularly outside the institution, found his policies to be a refreshing change of direction after fourteen years of relentless expansion under Eric Walker.

For the first time since the Pinchot era, the University found itself dealing with a governor who showed a lack of interest in and sympathy for the institution. Milton Shapp, a self-made millionaire and maverick Democrat from the Philadelphia area, won election in 1970 by portraying himself as a responsible businessman who could clean up Pennsylvania's fiscal mess. He pushed hard for a personal income tax, which the General Assembly enacted during the first year of his administration. Buoyed by the new tax and a healthy economy, the Commonwealth's revenues rose steadily until an embarrassed governor reported an all-time record budget surplus of $437 million in 1974. Tax cuts followed, yet Pennsylvania finished the next year with a $252 million surplus. Shapp was then in his second term, having been the first chief executive to benefit from a constitutional change that permitted governors to serve two consecutive terms.

Higher education did not share in this prosperity. During his 1970 campaign, Shapp had called upon the Commonwealth to provide a college education free of charge to all citizens who wanted one and could meet rather minimal academic qualifications. Once he took office, that kind of talk was not heard again. It was not that the governor opposed on principle the notion that the state should spend the huge sums of money that free higher education would have required. For all of his reputation as a thrifty businessman, Shapp spent more money during his terms of office-even after allowing for inflation-than any of his predecessors. But he was more interested in social welfare and social Justice programs than in education, and his budgets reflected those interests.

Popular opposition to those priorities was not sufficient to convince the General Assembly, where at least one chamber was always controlled by the governor's party, to override them. In most years, Penn State and other state-owned and -aided colleges and universities received significantly smaller appropriations than they had requested. In 1975-76, for example, Penn State received $102.7 million, its first appropriation above the $100 million mark and about $40 million more than either Pitt or Temple received. On the other hand, the allocation was only 6 percent larger than the previous year's and therefore several percentage points below the annual inflation rate. It was also $12 million less than the amount requested by the University. At least the allocation came on time. The legislature still suffered from a want of forceful leadership and an excess of partisanship. The budget for 1975-76 was the first in five years to be approved before the beginning of the new fiscal year.

Unlike governors Scranton and Shafer, Milton Shapp made no distinction between Penn State and the other state-related universities in regard to the Commonwealth's financial responsibilities toward them or to the roles they were expected to play in Pennsylvania's educational future. The Shapp administration believed that all state-related universities should pay a greater share of the cost of instruction, up to about 50 percent. This figure could be reached only if those institutions raised tuition rates. But to alleviate the financial burden on students, Shapp proposed to give more money to the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency for loans and scholarships. Students who needed financial aid would receive it; those who did not would help to subsidize their less fortunate brethren.

Students rally on the steps of Old Main in September 1977 demanding a higher sate appropriation for the University. In attendance are President Oswald and, to his left, state senator J. Doyle Corman.

One problem associated with that approach was its failure to take into account the plight of middle-class families, many of whose incomes were too high for their children to qualify for assistance from the PHEAA or the institutions they wanted to attend, but too low to cope with the rising costs of higher education, especially if there were two or more children of college age. Undergraduates (Pennsylvania residents) at University Park paid $365 per term for tuition in 1975-76, up 60 percent in five years.

Another difficulty was the Commonwealth's failure to uphold its commitment to the PHEAA. Heavy spending on other programs and a downturn in the economy produced budget deficits during the last three years of the Shapp administration. The governor recommended tax increases. However, because of the widespread corruption that had been uncovered in state government-surpassing even the Earle scandals of the 1930s-Shapp had lost nearly all his influence with the legislature, and his once enormous popularity among the voters had dwindled to almost nothing. His calls for tax hikes and tax reform went unheeded. In the General Assembly, which was preoccupied with uncovering corruption and refused to take a definite stand on finding additional sources of revenue, higher education did not get the attention it required.

Rising costs seemed to be the only issue in the post-Vietnam War era capable of arousing students at Penn State and other institutions in the Commonwealth to mass protest. The largest demonstration at University Park occurred on May 8, 1975, when more than a thousand students gathered on the lawn of Old Main to express their outrage at continued tuition increases. About a hundred protestors stormed Old Main chanting "We want Jack" and demanding to see the president; when it became clear that this would not happen, the group left without further incident. A month earlier, several hundred student government leaders from campuses across Pennsylvania had gathered in Harrisburg for a personal meeting with Milton Shapp. One angry undergraduate accused him of perpetrating "the educational genocide of the middle class." Another attempted to hand the governor a shirt. He had given the Commonwealth everything else he had for his education, he explained, so it might as well as have the shirt off his back, too.

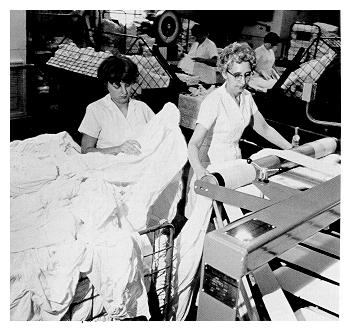

In 1967, the University recognized the Teamsters Union as the bargaining agent for more than 2,600 technical and service workers, ranging from electricians to janitors to laundry workers.

Students were not the only group to be caught in the financial squeeze. University employees felt its effects as well. The Oswald administration implemented periodic hiring freezes, reduced nonacademic services, and tried to hold the line on pay increases in order to keep operating costs down. It tried to distribute the burden fairly throughout the University community, but as the cost-cutting measures intensified, many of the institution's 2,600 technical and service employees- affiliated with the Teamsters Union since 1967-believed they were being asked to make more than their share of sacrifices. Their discontent finally erupted in a six-week strike in the summer of 1978. The work stoppage was triggered in part by a bid by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees to become the workers' new bargaining agent, which caused the Teamsters to take a more militant stance in its demands in order to preserve the loyalty of its membership. But there could be no hiding the disaffection of many employees with the University's position on wages and working conditions.

As for the faculty, many of them were unhappy with a budget recycling process, introduced at President Oswald's direction in 1972-73. At five-year intervals, each department had to return to the University's general fund a small percentage of the funds it had been allocated during that period. Departments could make yearly payments of varied amounts on their quotas in order to retain short-term flexibility. In the president's estimation, recycling softened the impact of financial duress by spreading it over a longer period of time, thus averting the necessity of having to make drastic cutbacks in any one year. Recycled monies could be channeled to where needs were greatest.

The University also took steps to increase the income it received from nonpublic sources. Private fund raising, after a promising start in the 1950s, had withered in the face of plentiful aid from state and federal governments. As late as April 1978, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported that the value of Penn State's endowment ($11,290,000) placed it 103rd among America's colleges and universities. By then, however, the University was already reinvigorating its private-giving campaign. In 1974, a new Office of Gifts and Endowments supplanted the Penn State Foundation as the primary solicitor of financial support from alumni, businesses, foundations, and other non-governmental benefactors. The office also helped individual colleges to promote gift giving. A Penn State Fund was created to act as beneficiary of all private gifts, and a Penn State Fund Council, composed of prominent alumni and friends of the University, was formed to advise the president and the trustees on fund-raising strategies.

During the first five years of its existence, the Office of Gifts and Endowments succeeded in more than doubling the annual rate of private giving. (In 1978-79, $10.3 million was collected.) By 1983, total gifts to the University since the formation of the Penn State Foundation in 1952 surpassed $145 million (exclusive of the Hershey grants), of which alumni contributed about $27 million. The endowment totaled about $25 million. The board of trustees and President Oswald set still higher goals, and in the early 1980s the coordination of private giving was again reorganized, ultimately coming under the supervision of a new Vice President for Development and University Relations.

Penn State's financial condition reached a low point in 1977. In August of that year, the General Assembly failed to approve any non-preferred appropriations when it passed the state budget. A category created during the budget reforms of the early 1960s, non-preferred appropriations went to those institutions, such as the state-related universities, which performed vital public functions but which were not owned or controlled by the state. The legislature did not have a legal obligation to make non-preferred appropriations; it did so from social and political necessity. But in 1977, granting the non-preferred funds meant raising taxes, a chore so repugnant that lawmakers put it off until five months into the new fiscal year.

Students from each of the University's colleges annually conducted "phonathons" to solicit financial support from alumni and to keep them up to date on University developments.

In the interim, the University had to find money elsewhere to continue operating. Tuition was raised to $421 per term for undergraduates at University Park and $378 at the Commonwealth Campuses. Nonresidents of Pennsylvania paid more than double these rates. Penn State also borrowed money and spent $380,000 in interest on loans. The University of Pittsburgh and Temple University made even larger interest payments, none of which the Commonwealth reimbursed. In all three cases, the universities finally received appropriations identical to those of the previous fiscal year ($106.7 million for Penn State). Never since the bleak years of the Great Depression had the land-grant institution failed to get at least a nominal increase in its funds from the state.

It was neither the first nor the last time the legislature passed the preferred budget before approving non-preferred appropriations. To make the University's relationship with the state less precarious, the Oswald administration considered having Penn State become state-owned, or at least giving the state more control over policy in exchange for a preferred budget classification. The conclusion was the same as those that had been drawn from similar studies previously: to give up independence of action would not be worth the modest financial advantage gained.

One of the few financial bright spots of the 1970s was the beginning of state aid to the College of Medicine. Officials of the Hershey Trust and the University had greatly underestimated how much money would be required to sustain teaching operations once the Medical Center was completed, and the cost of medical education and health care generally was rising much faster than anticipated. When President Oswald asked the General Assembly for help, political leaders quickly reminded him of Eric Walker's pledge that Penn State would not seek state appropriations for the Center. Oswald retorted that he did not feel bound by the promises of a predecessor and pointed out how valuable the unique facility at Hershey could be to all Pennsylvanians.

After much debate, the legislature approved an allocation for 1971-72 that amounted to about $7,500 per student, applying the same formula that it used to determine assistance to medical colleges at Temple University and the University of Pittsburgh. The subsidy was most welcome. Under the leadership of Dr. George Harrell and his successor (in 1973), Dr. Harry Prystowsky, the student population rose year by year. The graduating class of 1981 included 104 M.D.'s, more than three times the number in the first class a decade earlier.

Unfortunately, the student aid formula remained unchanged for more than a decade, while the cost of medical education soared. (Hershey officials estimated in 1981 that the cost of educating a physician had reached $30,000 per year.) From having one of the lowest tuition rates of any University-related medical school in the 1960s, Hershey came to have one of the highest in 1982-more than $6,000 annually for Pennsylvania residents. There was no direct state aid at all for the medical center's hospital, which had relied largely on private grants and federal funds for construction of a new basic science cancer research wing, a clinical services wing, an ambulatory care center, and other additions.

The neglect of higher education during the Shapp administration produced an inglorious legacy for the Commonwealth's colleges and universities. A survey reported in October 1978 in the Chronicle of Higher Education disclosed that Pennsylvania ranked 44th among all states in per capita spending on higher education ($59.32, compared with a national average of $78.67). In the mid-1960s, it had ranked 37th. The Harrisburg Patriot-News could easily have been describing most colleges and universities in the state when it stated in a March 20, 1977, editorial: "Penn State is in deep economic trouble-not the type that will force it to close its doors tomorrow but a problem that, should it continue, would doom the University to mediocrity."

The financial constraints on the University as a whole eased only slightly as a new governor, Dick Thornburgh, a Republican, took office in 1979. (He won reelection in 1982.) Pennsylvania remained in serious economic difficulty and in the early 1980s suffered its highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. Perhaps because of these problems, the Thornburgh administration and the legislature seemed more cognizant of the value of higher education. A Ben Franklin Partnership program was created through which the Commonwealth provided selected universities (including Penn State) with funds to promote the development of high-technology industries in Pennsylvania. Penn State's regular appropriations also increased, going from $111.9 million in 1978-79 to $159.8 million six years later. Yet even in 1984-85, state monies comprised only 45 percent of the University's general funds budget and represented a lower per-student appropriation than was awarded to the other state-related universities. Confronted with steadily mounting operating expenses, the board of trustees raised resident undergraduate tuition to $1,281 per semester for 1984-85-the seventeenth consecutive year that tuition had been raised. Tuition was slightly lower at Penn State than at the University of Pittsburgh or Temple University, but taking into account room and board and other expenses, the $7,500 annual cost of attending classes at University Park still presented a formidable burden for most students.