The board of trustees broke with precedent in two ways when it picked a successor to Milton Eisenhower. First, the trustees made their choice within weeks after Eisenhower disclosed his intention to resign. Furthermore, they selected a person already on the faculty-the first time a president had been named from within the ranks of the institution since John Fraser's election in 1866. Their choice was Eric A. Walker, whom Eisenhower had only recently named to the newly created post of Vice President for Research.

Eric Walker and Planned Growth

The trustees never seriously considered any other candidates. They knew the next president had to be an experienced administrator. Walker had headed the Ordnance Research Laboratory for eleven years and had also served for five of those years as Dean of College of Engineering and Architecture, one of the largest units of its kind at any American university. The trustees were also aware that Samuel Hostetter, the University's chief financial officer, had come to rely on Walker to assist him in carrying out many of the institution's nonacademic functions-representing the University in its dealings with technical and service employees, for example. Walker had therefore gained a familiarity with Penn State's operations far beyond the engineering college and the ORL.

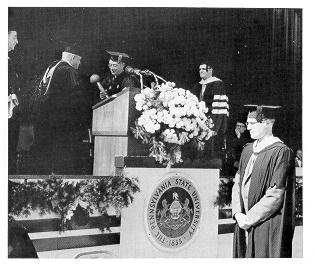

On behalf of the board of trustees, George H. Deike presents the University mace to Eric Walker at his 1956 inaugural.

Eric Walker was an appropriate choice in other respects. The close ties he had built up with the Department of Defense (where he headed a major research unit while on leave from the University), the National Science Foundation, and other governmental agencies, not to mention some large private corporations which he served as a consultant, could be as advantageous for the University as a whole as they had been for the College of Engineering. And of no little consequence was the fact that he enjoyed the enthusiastic and unconditional endorsement of Milton Eisenhower, who had recommended Walker to the trustees in the first place.

Eric Arthur Walker was the closest thing to a native son of the Commonwealth to preside over Penn State since Joseph Shortlidge. Born in Nottinghamshire, England, in 1910, he came to the United States by way of Canada in 1923 and settled in Wrightsville, York County. Young Walker excelled in science and mathematics in high school, where he also made a name for himself in track and field. His athletic prowess was sufficient to win him a $100 athletic scholarship from Penn State, which he almost accepted before declining it in favor of a $500 academic scholarship from Harvard University. Receiving a bachelor of science in engineering from Harvard in 1932, he remained there for three more years to earn a master's degree in business administration and a doctorate in science. He taught at Tufts University and headed the electrical engineering department at the University of Connecticut before returning to his alma mater in 1942 to work at the Underwater Sound Laboratory.

Another aspect of Walker's selection as the University's twelfth president that set it apart from previous presidential appointments was the mixed feelings that it generated within the Penn State community. To expect unanimous acclaim for anyone promoted from within was unrealistic. Some fellow deans and other faculty who had known Dr. Walker did not care for his blunt manner or his sometimes sarcastic sense of humor or his indifference to some of the sacred cows of academe. He disliked attending lengthy faculty meetings, where endless hours could be expended debating minor syntactical changes in an even more inconsequential resolution, or plowing through abstruse reports that were models of professorial pedantry. Walker was used to running things his own way and in a manner that put a premium on getting results quickly and efficiently.

Misgivings about the new president went deeper than clashes over style or personality, however. Some faculty, especially in liberal arts, questioned the wisdom of having an engineer head the University. Would not Eric Walker favor the engineering and scientific disciplines and continue to relegate the arts and humanities to second-class status? Could an engineer be a true scholar of the type that ought to lead a major university? One disgruntled professor even wrote to Harvard asking for proof that Walker really had earned his doctorate. While the president was most popular in the technical colleges, he was not without his critics there, either. Although he had never officially assumed the post of Vice President for Research, the very existence of that office meant, as President Eisenhower had intended, more centralized control over the University's sprawling research activities. Some deans and senior faculty resented any intrusion into what had been their own independent spheres of operation.

The lack of prior consultation rankled more faculty than any other feature of Walker's elevation to the presidency. The trustees conducted no prolonged search; they sought no advice from faculty representatives. The shock of Eisenhower's resignation had barely worn off when the instructional staff was presented with the fact that Eric Walker was the new president.

Walker formally succeeded Eisenhower on October 1, 1956. He shared his predecessor's desire to make Penn State nationally respected for the caliber of its instruction and research. To that goal, Walker added another: to prepare the University to meet the demands of the mid-1960s, when massive enrollments of youths born in the postwar boom could be expected. President Walker set the theme for his administration in his inaugural address. "We must strive for quality and quantity," he declared. "Our challenge is the challenge of mass excellence."

The first step in meeting this challenge was to prepare a blueprint for the University's growth over the coming decade and a half. In 1957, Walker named a panel of faculty and administrators chaired by C. S. Wyand to prepare a plan of development. Using the most conservative estimates to calculate the minimum needs for the University, the Wyand group predicted that full-time undergraduate enrollment at University Park would surpass 25,000 by 1970. About 10,000 students would be attending the branch campuses, their numbers equally divided between undergraduates and candidates for associate degrees. As increased emphasis was placed on advanced degrees, the ratio of all undergraduates to graduate students was likely to change from the current ten to one to something closer to seven to one. The colleges of Business Administration, Engineering, Liberal Arts, Chemistry and Physics, and Education were expected to absorb the bulk of the increase in student population at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

To accommodate a student body that would more than double its size in ten years, $168 million worth of new buildings would be needed at the main campus alone. The University's consulting architects, the firm of Harbeson, Hough, Livingston and Larson (successor of Day and Klauder), were commissioned to draw up a general building scheme. The University could finance nearly half the new construction, mainly residence halls, through bond issues. Most of the remaining funds would have to come from the Commonwealth, either directly or through the General State Authority. The Commonwealth would also have to be relied upon to provide a large portion of Penn State's operating and maintenance expenditures, which were expected to rise from $33 million in 1955-56 to $100 million by 1970, reflecting expanded housing and food services, physical plant care, higher wages and salaries to a larger work force, and numerous other costs associated with institutional growth. The Wyand study anticipated that the University would encounter no financial difficulties so long as the legislative appropriation continued to comprise between 38 and 40 percent of the institution's operating budget. Thus the $26 million allotted by the General Assembly for 1955-57 would have to swell to $80 million by 1969-71 (not allowing for inflation).

The Wyand report delineated the magnitude of the tasks facing Penn State. Could the Commonwealth be counted on to insure that its land-grant institution had the resources to meet these challenges? Under the guidance of Milton Eisenhower, the University enjoyed the most satisfactory relationship it had yet experienced with Pennsylvania's political leaders. However, the worsening condition of the state's economy made future relations uncertain. Pennsylvania had been suffering from a gradual economic decline for decades. Steel, coal, and railroads-the life blood of the Commonwealth-had fallen upon hard times, and alternative industries were slow to emerge. As late as 1947, Pennsylvania still ranked second in the nation in the value of its manufactured products. Within ten years it has slumped to fifth place. The impact of a mild national recession in 1957 was magnified in Pennsylvania, where nearly half a million persons could not find work. The 10 percent unemployment rate was the highest since the Great Depression. Under such conditions, state and local governments were hard pressed to raise adequate revenues.

As President Walker and other educators pointed out, the Commonwealth's economic malaise made increased spending on education imperative. The upgrading of educational facilities should be an integral part of any plan for economic redevelopment. People had to be employed productively if prosperity were to be recovered, and education was vital to boosting productivity in practically every field of economic endeavor.

Governor George Leader agreed, and in 1957 he presented to the General Assembly a plan for upgrading the state's higher educational system. Under his proposal, up to 20,000 undergraduates would be eligible for direct financial grants (scholarships), and several times that number would receive low-interest loans. A dozen or more public Junior colleges, comprising a network similar to those already in operation in California and New York, were to be established within easy commuting distance of the preponderance of the Commonwealth's students. The scheme was to be financed chiefly through a penny-a-bottle tax on soft drinks. Some observers wryly noted that given the popularity of soda pop, most students attending college on state scholarships or loans would still come close to paying their own way. Others observed that under the governor's plan, students who drank their way through college should perhaps be applauded rather than condemned.

Members of the legislature did not see much to laugh about in the governor's proposal. Leader had already put before them the largest biennial budget in Pennsylvania's history, one that if not trimmed would far exceed revenues. Loath to enact new taxes and skeptical that such an ambitious plan for higher education could be underwritten by a mere soft drink levy, lawmakers shelved it with hardly any debate.

Not long after legislative chieftains had buried the governor's recommendations, an event occurred that was to have profound repercussions for all of American education. In October 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik, the first man-made earth satellite. Sputnik convinced American citizens and their governmental leaders that the Soviets had forged ahead of the United States (which was not able to put its own, much less sophisticated satellite into orbit until January 1958) in the knowledge race as well as in the space race. Brain power had really sent Sputnik skyward, not rockets. If the USSR were permitted to retain its apparent lead, the free world would be doomed. Education was seen as essential to the survival of a free society. Training in science and engineering was regarded as most valuable, but all education, from kindergarten through college, was a natural resource that had to be more fully exploited as a defense against totalitarian domination. Public spending on education rose accordingly.

At the national level, a direct offshoot of Sputnik was the National Defense Education Act, passed by Congress in 1958. It allocated millions of dollars to improve basic and higher education in the sciences, mathematics, English, foreign languages, and other fields. Among its most important provisions was one creating a huge loan fund for college students. By 1960-61, 1,379 Penn State undergraduates were receiving $395,000 through the NDEA, making it the largest single source of student financial assistance at the University.

Pennsylvania, too, greatly increased its spending for education, but mainly at the elementary and secondary levels. Governor David L. Lawrence, elected in 1958, did not manifest the same interest in higher education that his predecessor had, and he made no effort to revive Leader's plan for loans, scholarships, or community colleges.

Penn State requested an appropriation of $44 million for the 1959-61 biennium. At legislative budget hearings, President Walker warned that the $34 million Governor Lawrence had recommended would permit no further growth of curriculums or enrollment at the University and would do a great disservice to the youth of the Commonwealth. The governor's budget would put Penn State's long-range plan in jeopardy.

Realizing that its chances of getting an extra $10 million were bleak, the University sought a compromise. The board of trustees voted to raise tuition (the term "Incidental fee" had finally been discarded) for Pennsylvania residents from $177 to $240 a semester and from $375 to $480 for out-of-state students. The increases would bring in an additional $3.7 million, enabling Penn State to ask the Commonwealth for only $40 million. The use of a tuition increase as a bargaining tool had no precedent in the institution's history and was adopted with extreme reluctance. A University study had revealed that 34 percent of Penn State's students came from families whose income averaged less than $5,000 annually, and 64 percent came from families whose average yearly income was below $7,000.

The General Assembly was unmoved. It passed an appropriation of $34.2 million for the University, and even that amount came four months late. Engaged in another of its wrangles over how much revenue should be generated from what kinds of sources, it had not put the Commonwealth's budget on the governor's desk until November 1959.

Voters that year approved a referendum authorizing the legislature to meet annually (instead of every two years) to discuss revenue matters. The change spelled the end for the biennial budget system, as Pennsylvania embarked on an annual budget calendar beginning in 1961. University officials henceforth had to prepare for budget battles more often. This disadvantage was offset by the fact that under the new system, the Commonwealth's allocations could more readily keep pace with the University's changing requirements. In practice, the new arrangement had little effect on Penn State's financial fortunes. Appropriations for both 1961-62 ($18.6 million) and 1962-63 ($20.4 million) were both considerably below the totals the University estimated it needed.

The failure of Penn State to obtain what it considered to be adequate funds from the Commonwealth could not be attributed to political partisanship. In many states, public universities were little more than political pawns at appropriations time, manipulated by one party or another or faction thereof in the interest of gaining advantage with the voters. That was not the case in Pennsylvania. To be sure, David Lawrence, a former mayor of Pittsburgh, was as zealous a Democrat as ever occupied the governor's mansion. He had gained statewide prominence in the 1930s as the most influential member of Governor Earle's cabinet and later served as state chairman and national committeeman of his party. Penn State, on the other hand, had a distinctly Republican flavor. It drew a majority of its students from rural areas and suburbs, where the Republican party was always strong. Its board of trustees, too, generally exhibited a Republican outlook on political issues, if for no other reason than because twelve of its members were chosen from two economic sectors-agriculture and industry-whose leaders traditionally leaned toward the GOP. Typical were two of the board's most distinguished members, Roger Rowland and Kenzie S. Bagshaw. Rowland, who became board president in 1963, not only presided over New Castle Refractories but also headed the Pennsylvania Manufacturers Association. The PMA since World War I had been one of the most important Republican lobbying organizations in the Commonwealth. Bagshaw, a board member since 1938, was master of the Pennsylvania State Grange, another group whose loyalty to the Republican party had been proven over many decades.

Yet Penn State's appropriations were rarely imperiled by inter-party bickering. Eric Walker was careful to maintain good personal relations with the governors and legislative leaders of both parties and was always welcome in their offices. So were most of the trustees, such as James B. Long '07, an alumni delegate on the board since 1943 and its president from 1958 to 1963. A nationally recognized designer and builder of bridges, Long had done business with the Commonwealth for many years and knew his way around the political hallways of the capitol. And neither Leader nor Lawrence departed from the practice of previous Republican governors in making the six gubernatorial appointments to the board of trustees. They sent the names of no nominees to the Senate for confirmation without first receiving informal approval of their candidates from Penn State's president.

The University's legislative representatives in Harrisburg also worked effectively to maintain good relations with Democrats and Republicans alike. C. S. Wyand labored earnestly on behalf of Penn State and was widely respected among state leaders as a man of unblemished integrity. Edward L. Keller, formerly head of General Extension, became Vice President for Public Affairs in 1964 and assumed responsibility for governmental relations. "Ed" Keller was a hearty, gregarious sort who was on a first-name basis with practically everyone in state government from the governor on down. He reveled in political backslapping and was well liked by nearly all who met him.

President Walker and other University officials who dealt with political affairs thought of Penn State as the mechanism through which first George Leader and then David Lawrence learned about higher education, a topic about which governors before and since knew relatively little. Walker believed that whenever possible, the University's needs had to be placed within the context of what the institution could do for the betterment of the Commonwealth in, say, mineral industries or agriculture or teacher training. A professor of animal husbandry, William L. Henning, served as Secretary of Agriculture under Governors Leader and Lawrence, his eight years of public service exemplifying Penn State's traditional function as a reservoir of high-level state and federal officials. It was not a case of what Pennsylvania could do for Penn State, therefore, but what Penn State-adequately supported-could do for Pennsylvania. The governors and other political leaders were gently reminded that as the land-grant school, the University had specific legal responsibilities to the Commonwealth. In turn, Pennsylvania had a financial obligation to Penn State that it did not have to Pitt, Temple, or the University of Pennsylvania, which were also making efforts to increase their state appropriations.

There were critics who contended, in an argument first raised during John Thomas' administration forty years earlier, that Penn State wanted the best of both worlds: it wanted preference in state appropriations without being subject to state control. The state teachers' colleges, which the legislature in 1959 permitted to add liberal arts curriculums, were owned and operated by the Commonwealth and did not have the freedom, of action enjoyed by the four state-aided universities. But the independence of three of these universities meant relatively small appropriations. Only Penn State had administrative freedom and large appropriations. In 1959, in the last biennial budget, legislative and GSA allocations totaled $56 million for the fourteen state colleges, $44 million for Penn State, $10 million for the University of Pennsylvania, $7.3 million for the University of Pittsburgh, and $4.5 million for Temple University.

For a time, University officials considered sacrificing some of their institution's freedom in exchange for even larger appropriations, assuming that the Commonwealth would give Penn State more money if it could exercise greater control over how it was spent. President Walker discussed this possibility with Governor Lawrence, who had no objections to it. However, further study indicated that the freedom given up-perhaps in the form of additional state representatives on the board of trustees-would not be worth the few million dollars that the change might bring.

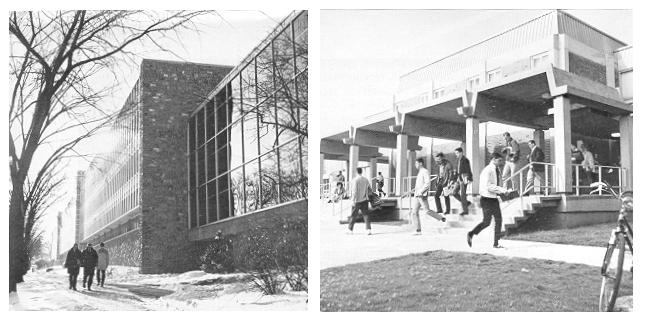

(Left) Hammond Building, home of the College of Engineering; (right) College of Education students change classes at Chambers Building.

Pennsylvania's economic troubles, rather than politics, in combination with the fiscal conservatism of both Democratic and Republican legislators, were primarily responsible for the levels of Penn State's appropriations during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Governor Leader was inclined to be a free spender but couldn't convince the General Assembly to go along. David Lawrence, by contrast, was even more financially tightfisted than many members of the legislature, his credentials as a liberal Democrat notwithstanding. Moreover, political leaders felt no great pressure from their constituents to approve larger outlays for colleges and universities. Pennsylvania was already allocating vast amounts for basic education. It provided about fifty percent of the income of local public school districts, compared with a national average of about forty percent. And it was assisting so many institutions of higher learning-four major universities, the state colleges, and assorted professional schools-that to increase the appropriation only slightly for each meant a substantial total increase for the state.

While Penn State officials were dissatisfied, they privately conceded that their institution was doing as well as could be expected under the circumstances. The University benefited immensely from grants from the General State Authority, which between 1957 and 1962 spent $14.2 million for new buildings at University Park and allocated $17.2 million more for future projects. These grants required approval from the governor, who served as chairman of the Authority. That the University got virtually whatever it needed from the GSA was another testament to its good relations with both Leader and Lawrence.

The biggest disappointment with the Lawrence administration among higher education officials throughout Pennsylvania was its failure to develop a master plan. A master plan could identify what functions the University, the state colleges, the state-aided universities, and other schools were to have and how each institution would interact with the others. A master plan could indicate the long-range costs of development, so that governors and legislators might plan for the distant future rather than from one fiscal year to the next. It could also resolve the question of what, if anything, the Commonwealth should do to stimulate the growth of junior or community colleges. In the absence of a plan for the development of an integrated educational system, Pennsylvania extended its financial support in piecemeal fashion. How to meet the challenges of the coming decade and beyond was still left to the 130-odd colleges and universities to decide for themselves.

Striving for Quantity and Quality

Penn State was able to adhere to its own master plan for development relatively closely, in spite of its claim that legislative appropriations were inadequate. Additional revenue was secured through higher student fees. Comprising 17 percent of the University's total income in 1957-58, student tuition and other charges accounted for 22.5 percent five years later. Pennsylvania residents were paying $525 per academic year in tuition by 1962-63, with total yearly costs, including living expenses, rising above $1,800 for most students. Nevertheless, the number of applications for admission climbed steadily. Full-time enrollment for 1962-63 reached 19,300, only slightly behind the projections made in 1958. The University ranked as the twelfth largest institution of higher education in the nation.

Rapid growth was visible not only in the increased number of students shuffling to and from classes, but also in the tremendous amount of new construction that was being undertaken, particularly at University Park. Buildings were going up at a rate surpassing the boom times of the 1930s. The General State Authority financed most projects. Between 1957 and 1962, six major new academic structures were added to the physical plant: a general engineering building (Hammond), a military science building (Wagner), the Chemical Engineering Laboratory (Fenske), the Education and Psychology Building (Chambers), a second electrical engineering building, and a building to house the fine arts departments. Meat processing and swine laboratories, turkey breeding houses, and a variety of other agricultural research structures were erected around the northeast periphery of the campus. Enlargements of existing buildings included new wings for Recreation Building (until 1957, Recreation Hall), the Main Engineering Building (Sackett), the Home Economics Building (Henderson), and the Agricultural Engineering Building.

Bond issues continued to be the chief means of paying for the construction of dormitories and dining halls, although the University did borrow money occasionally from the Federal Housing Administration. Once the dimensions of the anticipated enrollments of the 1960s and beyond had become known, the Walker administration decided to accelerate the rate of building new residence halls. The only alternative was to have private, off-campus landlords to meet most future housing demands, a course of action that had too many uncertainties to be relied upon to any great degree.

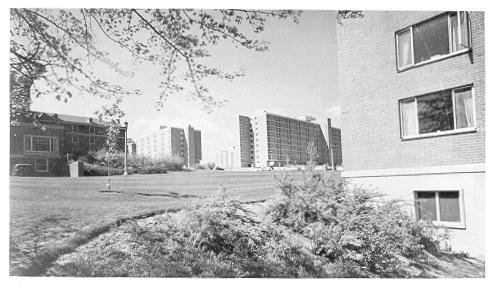

South Halls, a dormitory complex for a thousand women that was authorized late in the Eisenhower administration, opened in the fall of 1956 along East College Avenue. Work on a North Halls complex of four twin-unit dormitories and a dining hall began in 1958. Located along Park Avenue, the northern dividing line between town and campus, North Halls accommodated about a thousand men and was ready for occupancy in 1959. Construction had hardly begun when the trustees approved two even larger residence hall projects. Pollock Halls, on the site of the Pollock Circle temporary housing units, originally consisted of four dormitories housing 1,100 women and three dormitories having space for a like number of men, along with dining hall facilities. Carrying a price tag of about $23 million, it was the single most expensive residential hall venture for Penn State and was completed in 1960. The second project, East Halls, was the dormitory complex farthest removed from the central campus. It initially comprised four dormitories built on land that not long before had been part of the University farms. The first units of East Halls opened in 1961. In 1962 plans were announced for the construction of two more residence halls for both East Halls and Pollock Halls. Their completion two years later brought the number of undergraduates living on campus to nearly 11,000.

Pollock Halls, framed by portions of Simmons and Haller (South) Halls

It was ironic that Penn State, which had for so many decades shunned campus housing, had now become a leader among universities in the number of students residing in institutional dwellings. The logistics of providing support services for dormitory dwellers were difficult to comprehend. The University employed over 500 full-time and 800 part-time workers in its food services alone. These employees served more than five million meals each year in the eight dining halls and the Hetzel Union Building. The cost of food, which included 30,000 pounds of sugar and 40,000 loaves of bread each month, ranged upward of $3 million annually.

Additional housing was also needed for graduate students. When more dormitory space became available for coeds, the old Women's Building became available for unmarried graduates. A more urgent demand existed for accommodations for married graduate students almost half the graduate population-since they had fewer alternatives at their disposal in seeking quarters off campus. Eastview Terrace was too small and had a long waiting list for vacancies. In 1958, the trustees authorized construction of a new complex, Graduate Circle, farther to the east of Eastview. Opened in 1960, Graduate Circle could accommodate more than 200 graduate students and their families. Rental fees compared favorably with those charged for apartments in the community, because the University set rates at both Graduate Circle and Eastview Terrace only high enough to recover costs. As in the case of undergraduate residence halls, housing for graduate students was not meant to be a profit-making venture.

Keeping abreast of the University's physical growth was the expansion of its curricular offerings. In 1956-57, the undergraduate catalog listed 68 separate major baccalaureate fields and options; by 1962, that number had risen to 130. The trend was toward increasing specialization in existing fields rather than initiating entirely new fields of study. In the early 1960s, for example, an undergraduate majoring in electrical engineering could choose from degree options in electronics, power generation, aerosystems, and industrial automation. A student pursuing the curriculum in food science and housing administration had the opportunity to specialize in hospital dietetics, commercial food service, institutional resident management, or school food service. A similar phenomenon was occurring at the graduate level. The associate degree programs had proven extremely popular and were expanded to seven fields by 1962: electrical technology, drafting and design technology, business administration, chemical technology, production technology, surveying technology, and housing and food service. The engineering technology fields were by far the most popular. The College of Engineering was awarding over 1,500 associate degrees annually by 1960.

Research activities also remained prominent. Total University outlays for organized research surpassed $14.4 million or 21 percent of the budget in 1962-63. These funds were increasingly channeled to programs that emphasized interdisciplinary investigation-the Center for Air Environment Studies, the Institute for Research on Land and Water Resources, and the Materials Research Laboratory, to name but a few. With the cooperation of the state government, the University founded the Commonwealth Industrial Research Corporation to attract new research and development businesses to Pennsylvania and to stimulate existing ones. Penn State's primary share of the CIRC's responsibilities was to make its faculty and equipment available on a consulting basis for firms moving to or expanding within the Commonwealth and to conduct special courses and symposiums for the benefit of such firms.

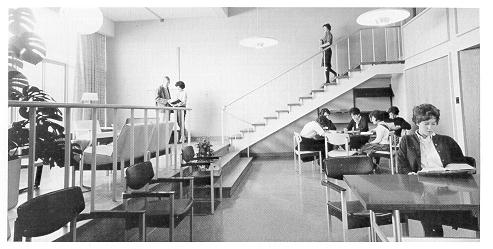

North Hall lounge

As research efforts expanded, new avenues of disseminating the results of such work were called for, and this led to the formation of The Pennsylvania State University Press. Faculty and trustees had discussed the merits of a press since the late 1940s, and Milton Eisenhower had given the idea his personal backing, but not until 1956 were sufficient funds available for the press to be organized. Its objective was to publish worthwhile manuscripts that, because of limited readership, could not find an outlet among commercial presses or large academic publishers. The press handled business, editorial, and marketing tasks and contracted for printing and binding. Its first book was Toward Gettysburg, a biography of Civil War General John F. Reynolds written by Edward J. Nichols of the English department and published in 1958.

The magnitude of Penn State's expansion made fundamental internal changes inevitable. One of the most important occurred in the administrative structure of the University. Eric Walker was not satisfied with the organization as he found it, deeming it inefficient and unsuited to cope with the additional responsibilities that accompanied institutional growth. He desired a system in which administrators would have a more precise idea of what was expected of them and of the boundaries that separated their duties from those of other administrators. He planned a new kind of administrative organization for Penn State based in large part on the successful managerial techniques he had observed as a consultant in industry and government.

This restructuring coincided with the departure of two senior administrators who had served the University for a combined total of more than seventy-four years. Provost A. O. Morse, tired of academic life, left early in 1956 to take a position with the American diplomatic service in India. Sixty-eight-year-old controller and treasurer Samuel Hostetter announced his intention to retire by July 1 of that year. Although not well known among students and alumni, Hostetter was thought of by many Penn State faculty and staff members as the real president of the institution in nonacademic matters. Both Hetzel and Eisenhower had allowed him an unusual degree of independence and nearly always deferred to his judgment on questions involving finance, physical plant, purchasing, and employee relations. More than any other person, Hostetter should be credited with preserving the University's fiscal integrity under some of the most adverse conditions the institution had ever faced. Eisenhower and Walker recognized his value and persuaded him to stay an extra year as treasurer (the controller's duties were organized into a new and separate office) in order to supervise contracts and loans still pending and help smooth the transition between presidential administrations.

At Walker's request, the board of trustees in 1957 authorized the creation of several vice presidencies that formed the core of the new administrative structure. Succeeding Hostetter in the post of Vice President for Finance was McKay Donkin, a geological engineer and oil entrepreneur. Since 1951 Donkin had been serving as special assistant to Atomic Energy Commission chairman Lewis Strauss, in which capacity he had become a close friend of President Walker. Certain responsibilities once handled by Hostetter—mainly in building construction and maintenance, food and housing services, personnel, and security-were reorganized under a new Vice President for Business Administration. Ossian MacKenzie was named to that post but left after a year to resume his full-time duties as dean of the College of Business Administration; he was replaced by Albert R. Diem '35, an executive with the Dictaphone Corporation. Michael Farrell, associate dean of the College of Agriculture and director of the Agricultural Experiment Station, became Vice President for Research. Provost Lawrence Dennis was given the new title of Vice President for Academic Affairs and C. S. Wyand became Vice President for Development. This organization remained essentially intact throughout the remainder of Walker's administration, although changes in personnel did take place, of course.

The suddenness with which the number of University administrators seemed to multiply irked many older faculty members. They missed the days when they could form a friendly relationship with "Prexy" and perhaps the half-dozen, subordinates who comprised his staff. They mourned the passing of the era when an instructor might send a communication to the president with the assurance that he would read it and respond to it personally. These conditions had not prevailed under Milton Eisenhower, but he was not a man that the faculty could readily criticize. Eric Walker was a more inviting target. Even in jest, their antagonism toward the growing bureaucracy was clearly visible. "The number of vice presidents, or 'veeps,' increases dally," lamented a professor of physics in a bit of 1960 satire. "Assistants to these 'veeps,' deans, associate deans, assistant deans, assistants to the deans, coordinators, division chiefs, directors of this and that, long-range planners, medium-range planners, short-range planners, supervisors., hypervisors, and ultravisors abound!" A liberal arts professor about that same time remarked that "the old adage, 'a form a day keeps the administrators at play,' is no longer valid. Two-form days are now common; and several four-form days have been reported." Such comments represented less a criticism of President Walker than a protest against the growing impersonality of the University. The clubby atmosphere prevailing among the faculty in an earlier era would not have survived into the 1960s regardless of who headed the institution.

The second fundamental change in the internal workings of the University involved the academic calendar. One of the first things President Walker asked of the University Senate was to study the feasibility of putting Penn State on a twelve-month schedule. Average summer enrollment in the 1950s was only one-third that of the fall and spring semesters, which Walker considered an intolerable waste of the institution's physical and human resources. If more students attended during the summer and could choose from a greater variety of courses than heretofore offered, they could graduate in as little as three years. Consequently, the University could graduate up to 25 percent more students using the resources already at hand. This increased efficiency would enable Penn State to deal more effectively with the growing demand for higher education and would not go unnoticed in Harrisburg, either. By persuading some of those students who preferred to take occasional time off from their studies to do so in a season other than summer, the demands on the University's services could be spread more evenly throughout the year, again resulting in lower costs. Faculty, too, could teach during the summer and, if desired, take a leave of absence at another time.

After Sputnik, the twelve-month calendar question took on a dimension that transcended dollars and cents. "This nine-month school year is archaic and has to go," President Walker declared in interview published in the Harrisburg Patriot-News in December 1957. "We can't afford it any longer, not only financially, but as a nation we can't afford it any longer." How could the United States successfully confront the challenge of the Soviet system unless it took the business of education more seriously?

The University Senate approached the issue with less enthusiasm. Two years of sporadic debate, during which questions were raised about the effect on sequential courses, faculty time off, and other details, culminated in February 1960 with the passage of a resolution stating that a year-round plan would not adversely affect the quality of education at the University. Therefore, the question of a calendar change was purely an administrative one and should be left to President Walker and the trustees. Walker assigned C. 0. Williams, his assistant for special services (and former Dean of Admissions and Registrar) to work out the mechanics of the new calendar, which became effective with the 1961 summer session. It consisted of four ten-week terms, divided by intervals of between two and four weeks. The standard class period was stretched from 50 to 75 minutes. The University continued to offer semester credits, and students could earn the same number of them (approximately 36) over three terms that they previously accumulated during two semesters. Tuition was likewise adjusted.

Some faculty members regarded the conversion to a term system as just another sign that Penn State was abandoning valuable parts of its academic heritage. To President Walker's chagrin, the letter that his office had distributed to notify members of the University community of the calendar change became a rallying point for his critics. Ghost-written by Lawrence Dennis and signed by Walker, the document began, "For some time, thoughtful observers of the contemporary scene have been disturbed by a tragic anachronism in American higher education: a horse and buggy calendar in a jet-age world." There followed several paragraphs equally pretentious and riddled with cliches.

A small band of faculty quickly capitalized on the satiric possibilities of the document and founded TOCS-Thoughtful Observers of the Contemporary Scene. The sole objective of TOCS, explained a member in a November 8, 1960, Collegian article, was "to preserve a campus atmosphere of scholarship and a pace of operation sufficiently unhurried to allow adequate reflection and/or meditation on the part of both faculty and students." The only formal aspect of the organization, which at its peak was said to include about 300 faculty, was the wearing of a plain white lapel button on which "TOCS" was printed in blue letters. Walker regarded TOCS mainly as a show of displeasure with Vice President Dennis-the wording of the document clearly pointed to his authorship-who was never popular with a large segment of the faculty. Its formation carried a more important message, however. It represented yet another protest by some members of the teaching staff against the growing impersonality of the University and the danger that it was being transformed into a "diploma mill."

TOCS was short-lived. Walker tried to take the organization in stride, appearing at a University Senate meeting wearing a TOCS button himself-a gray one rather than white, he explained, in keeping with the blend of good and bad that people found in his administration. This attitude helped to diffuse what could have evolved into a troublesome situation; but TOCS was too loose an organization to survive in any case, and its goal, however worthy, was probably unobtainable. By mid-1962 the little white buttons had disappeared.

Despite accusations to the contrary from within and without the University community, ample evidence suggests that Penn State did not sacrifice the quality of education for quantity during these years of stupendous expansion. In 1958, the institution accepted an invitation to join the American Association of Universities. This distinction, while bestowed largely in recognition of the achievements of Milton Eisenhower, hardly constituted a warning that Penn State ought to consider the quality of its programs more carefully. The AAU was then composed of thirty-seven of the most prestigious North American institutions of higher learning. Penn State, Iowa State, Tulane, and Purdue were the first schools invited to join since 1949. The Association's small membership belled the vast influence that this elite group exerted over the work, particularly at the graduate level, of all American colleges and universities, as well as on the policies of the federal government toward higher education.

Another sign that quality had not been relegated to a secondary position could be seen in the academic standing of Penn State's incoming students. Nearly 80 percent of the freshmen admitted in 1962-63 had graduated in the upper one-fifth of their high-school class, compared with 43 percent in 1956. Beginning in 1963, all applicants not in the upper fifth were required to take the Scholastic Aptitude Test administered by the College Entrance Examination Board, enabling admissions officers to become even more selective. Nevertheless, the University had difficulty attracting the most academically gifted high-school graduates. "In spite of the progress we have made," lamented President Walker, "Penn State is still not getting its share of the brightest students. Those who score 1500 or 1550 on the college board exams apply to several schools and use Penn State as a kind of insurance. If they don't make Harvard, Chicago, or MIT, they will take Penn State." The problem was that most of these students did make these elite schools, frequently because they were offered scholarships. Penn State's tuition and other fees were much lower, but the University had few financial aids that it could use to lure the very brightest students. And in most fields, a degree from Penn State or almost any other state university did not carry the same prestige as a diploma from certain private institutions.

To make sure that as many students as possible who did enter the University completed their education, a Division of Counseling was created in 1956 under the direction of Robert Bernrenter, Professor of Psychology and soon to become Special Assistant to the President for Student Affairs. Division personnel administered a battery of achievement, aptitude, and personality tests to freshmen during the summer before their arrival, and met individually with them and their parents on the campus. Counselors used the information thus gathered to advise freshmen on career choices and other academic matters. The Division of Counseling, which was an outgrowth of a more limited program Bernreuter had been running since the 1930s, put Penn State in the forefront among institutions of its size in the degree of personal attention incoming students received.

Upgrading the quality of instruction was as important as admitting better-qualified students. The University could not hope to attract or retain good teachers unless salaries were competitive with those of other institutions. Eric Walker, like Milton Eisenhower before him, made raising salaries one of his most important concerns. When Penn State did not receive the appropriation it wanted from the Commonwealth, expenditures on other items were usually eliminated or reduced so that money would still be available for salary increases. An informal survey taken by the president's office in 1962 revealed the average salary of a full professor at Penn State to be $13,900, up 24 percent since 1959. That figure was close to the average of $14,200 paid by ten other land-grant schools surveyed in the Northeast and Midwest. Salaries at those institutions had risen only 18 percent since 1959.

Also indicative of Penn State's emphasis on high quality was the series of departmental self-evaluations that began at President Walker's personal initiative in 1961. Over the next three years, all 70-odd academic departments in the University carefully analyzed themselves, reporting on what they considered to be their strengths and weaknesses and how weaknesses could be turned into strengths. At the end of the period of self-scrutiny three or four distinguished educators working in the same field but having no connection with Penn State or the staff of the department under study were called in to make an evaluation. They reported their findings orally to the president and then submitted a written summary to him and the departmental faculty. Walker considered this type of procedure to be superior to the decennial evaluations by the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools and almost on a par with evaluations done by such professional societies as the American Society for Engineering Education and the American Institute of Architects.

One of the most common academic weakness revealed by this self-study was the lack of coordination among departmental faculty in developing new curriculums. Too often a department's course offerings were shaped almost entirely by individual interests of faculty members, rather than consideration for making a well-balanced course of study available to the students. New members of the instructional staff were frequently added principally on the basis of their scholarly reputations, for example; their ability to fill gaps in a department's curriculum was a secondary consideration at best.

When personality conflicts coincided with curricular growing pains, the results could be acutely embarrassing. In the early 1960s, faculty in the School of Journalism found themselves embroiled in a debate over whether the curriculum should continue to be geared toward training newspaper journalists or expanded to include all communications media. So fierce were disagreements that the American Council on Education for journalism dropped the University from its list of accredited institutions until internal differences were resolved. The American Institute of Architects temporarily revoked accreditation of the University's architectural curriculum for similar reasons. The most highly publicized internal dispute occurred in the Department of Physics. Before they were resolved in 1963, differences of opinion over curricular and personnel matters involving the faculty, department head John A. Sauers, and Dean of the College of Chemistry and Physics Ferdinand G. Brickwedde created an uproar that attracted the attention of newspapers as far away as Pittsburgh.

Any effort to improve the overall quality of education at Penn State had to involve the humanities and fine arts. President Walker wanted-the College of Liberal Arts and School of Fine Arts within it to seek a higher profile within both the University community and the scholarly disciplines that comprised these academic units. This could best be accomplished, he believed, in the same way the technical colleges had achieved prominence-through increased research, public service, and other scholarly activity in addition to teaching. A reputation for excellence would attract higher-quality faculty and students. The administration consequently instituted a more generous policy of granting liberal arts faculty time off for research and made greater efforts (not always successful) to get more financial support for research and graduate students. A new fine arts building complex was also started near Hort Woods.

However, the administration was slow to increase support to the library, the principal laboratory of the humanist and social scientist. As late as 1962-63, the various University libraries received only 1.4 percent of the institution's operating budget, and an expansion of Pattee Library was still only in the planning stage. Michigan State and Ohio State, two universities with which Penn State administrators liked to compare their own institution, regularly spent more than 3 percent of their budgets on libraries; at Ivy League institutions, 5 percent was the budgetary norm. Penn State also suffered the ignominy of having been turned down a second time for membership in the Association of Research Libraries. In number of volumes held, the University did not even place among the nation's forty largest academic libraries. Head librarian Ralph McComb saw no hope that Penn State could build a research library equal to its needs unless it were willing to devote 4 percent of its annual expenditures to that purpose. The importance of adequate library facilities could not be overemphasized. The library reflected not only the institution's commitment to raising standards in the liberal arts but its commitment to scholarly excellence in all fields of study.

The Walker administration held that in addition to being more research-oriented, the liberal and fine arts should play a greater role in the general education of all Penn State undergraduates. Under a reorganization scheme developed by Vice President for Academic Affairs J. Ralph Rackley and approved by the board of trustees in 1962, the College of Liberal Arts and the new colleges of Arts and Architecture and Science formed the core of a new system of undergraduate instruction. All freshmen and sophomores were to take their coursework from these three colleges. At the beginning of their third year, their general education having been completed, students could enter any of the seven professional colleges or finish their studies in one of the core colleges.

The formation of the core college system presented a good opportunity to realign academic units. The microbiology, zoology, botany, and biochemistry departments were transferred from the College of Agriculture to the College of Science, which encompassed all the departments in the old College of Chemistry and Physics except for chemical engineering, which moved to the College of Engineering. The College of Liberal Arts lost the Department of Mathematics to the College of Science, but regained economics from Business Administration and psychology from Education. (As part of the Department of Education and Psychology, psychology had been transferred from Liberal Arts when the School of Education was created in 1923, and had become an independent department there in 1945, with Bruce V. Moore, a pioneer researcher in industrial psychology, as its head.) The College of Liberal Arts also lost the School of Fine and Applied Arts, which was joined with the Department of Architecture from the College of Engineering to form the College of Arts and Architecture.

The core college system was hailed as the first major curricular reorganization in more than a decade. It did bring about an increased amount of interdisciplinary work and made changing majors easier for students, since all colleges required the same type of foundation courses. But the change was not as great as it appeared on organizational charts: The service or general education function of most of the departments in the core colleges had always been dominant. Moreover, no sharp demarcation could be drawn between the applied studies that were supposed to be the responsibility of the professional colleges and the theoretical instruction that was to be handled by the colleges in the core. Arts and Architecture offered as much professional work as any of the non-core colleges. Moreover, some courses that were essential to a general education were offered by departments outside the core-the Department of Geography in the College of Mineral Industries, for example. In the long term, not nearly as much substantial change occurred as was originally anticipated.

Renewed Emphasis on Football

Eric Walker liked to tell a story about a conversation he had with his friend, the distinguished scientist Vannevar Bush, soon after being named president of Penn State. "Eric, there are three ways to build a great university," said Bush. "You can build a lot of buildings. You can build a football team. Or you can build a faculty." "Well, Van," Walker replied, "I am going to do all three."

Both men may have spoken with tongue firmly in cheek, yet there was truth in what each said. For better or worse, football was indeed one measure of a great university. Therefore, in addition to increasing the size of its physical plant and the quality of its faculty, Penn State steadily upgraded its intercollegiate football program throughout the 1950s and on into the next decade.

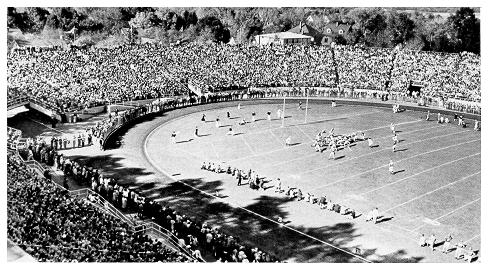

Action on Beaver Field

The turning point for football had come soon after the death of Ralph Hetzel. Members of the board of trustees and of the Athletic Advisory Board once again began to speak of the possibility of offering scholarships to athletes. Acting President Milholland, reversing a stand he had taken while president of the Alumni Association twenty years before, favored subsidizing athletes. Scholarships would enable Penn State to recruit better players, he argued, and a consistently winning team would garner sonic long-overdue national recognition for Penn State. When opponents of athletic aid pointed out that the football team had earned an invitation to the 1948 Cotton Bowl and a fourth-place ranking from the Associated Press that season without having any scholarship players, Milholland and others countered that the Cotton Bowl team was filled with war veterans in their mid- and late twenties. Their triumphs were unlikely to be equalled by later squads.

The catalyst for a change came at the end of the 1948 season when head coach Bob Higgins resigned for health reasons. The board of trustees considered the time appropriate for a change in policy as well as in personnel. In May 1949, the board's executive committee voted to institute one hundred athletic scholarships-most of which were to go to football prospects that would cover all tuition costs.

There were other indications that conditions were ripe for a renewed emphasis on football. Attendance at home games, especially by alumni and the general public, grew larger with each season. A few months before they approved the awarding of athletic scholarships, the trustees had authorized additions to Beaver Field that increased seating capacity from 14,000 to 29,000. To reap maximum financial rewards from the expansion, season ticket holders were to be given preferential seating. No longer could alumni or townsfolk buy tickets to one or two contests a year and expect to sit along the fifty-yard line. Furthermore, incoming President Milton Eisenhower, unlike Hetzel, did not object to subsidizing student-athletes so long as all aid was made public and administered by authorities of the institution rather than alumni. When he left Kansas State, that school had 55 football and 22 basketball players on scholarships. Although Eisenhower would have preferred that no colleges or universities grant any athletic assistance, he recognized the realities of the situation and what important non-athletic benefits could be conferred on an institution that fielded a winning football team. Finally, eagerness to return to the glories of the gridiron past was demonstrated in a grass roots campaign to find "a big-time coach for a big-time college" after the resignation of Joe Bedenk, Higgins' successor for just a single season. (Bedenk, head coach of the baseball team and an assistant football coach under Higgins, did not care for the pressures of his new job.)

Bedenk's replacement, if not exactly a "big-time coach," was at least popular enough to satisfy the clamor for a well-known personality to lead the Nittany Lions. Charles A. "Rip" Engle, a native Pennsylvanian, had coached at Waynesboro High School in the 1930s before moving to Brown University, where he became head coach in 1944 and compiled a 28-20-4 record over six years. To help Engle rebuild Penn State football, the trustee executive committee in March 1951 increased the number of athletic scholarships to 150 and added 50 grants-in-aid that equaled the cost of room and board. The Senate Committee on Scholarships and Awards administered the aid in compliance with the rules of the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference. Recipients had to meet the same academic standards for admission to Penn State as all other students and had to maintain the same rate of academic progress.

At first, Rip Engle expressed doubts about this policy of academic strictness. He maintained that most institutions that wanted winning football teams made concessions in regard to the scholastic standing of potential athletic recruits. Milton Eisenhower did not see any reason to make concessions, however, and neither did the new dean of the School of Physical Education and director of athletics, Ernest McCoy. Eisenhower's personal choice for the job, McCoy came to Penn State in 1952 from the University of Michigan to succeed Carl Schott, who was retiring. Michigan, where McCoy had been assistant athletic director, had policies similar to those of Penn State. Administrators controlled athletics, the coaching staff held academic rank, and student athletic aid was aboveboard and subordinate to academic regulations.

McCoy and Engle soon came to an agreement on athletic scholarships and grants-in-aid. When Engle and his staff went on recruiting missions to high schools in Pennsylvania and adjacent states, they checked first with the guidance counselor to review a student's scholastic status. Only then did they talk to the high-school coaches. "We lose a lot of kids that way," acknowledged Dean McCoy, "but we'd rather lose them before they get here than after."

With the encouragement of President Eisenhower, McCoy assumed responsibility for making the schedules for football and other intercollegiate sports. That assignment had formerly been the prerogative of the graduate manager of athletics, a post that represented the last vestige of direct alumni influence on athletics and one that McCoy soon eliminated. The new dean reasoned that since Penn State had made its move to become a football power, it ought to have a less provincial schedule. Consequently, games were arranged with Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, North Carolina State, and other schools that often boasted nationally ranked teams.

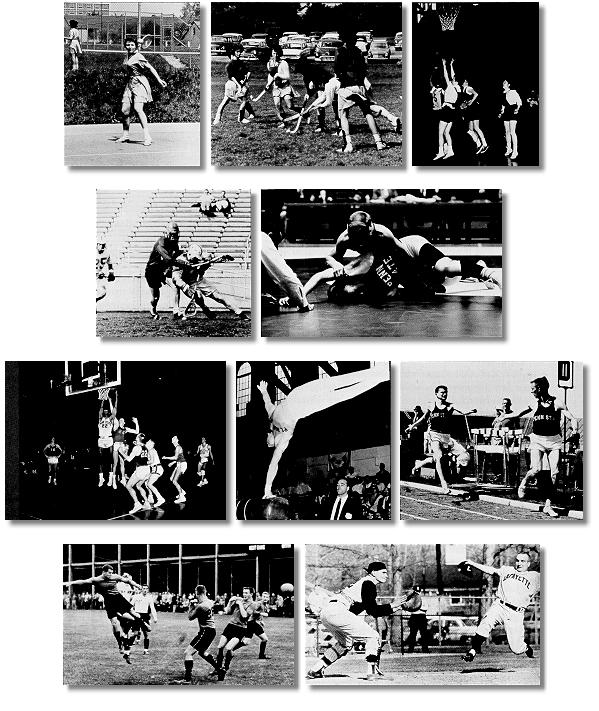

Athletics included more than football, certainly. In 1951, the number of varsity sports was reduced from 16 to 12 (fencing, swimming, skiing, and riflery were dropped) in anticipation of a reduction in income as enrollment declined from the record highs of the immediate post-war years. Nevertheless, Penn State still sponsored more varsity sports than most other institutions of similar size. In no field of athletic endeavor was the University more consistently successful than in soccer. Bill Jeffrey retired as head coach in 1952 after compiling 153 wins (including undefeated streaks of 65 and 21 games), 24 losses, and 27 ties in his 26-year career. It was an achievement unparalleled in American collegiate soccer. His successor, Ken Hosterman, coached the team to the NCAA national championship in 1954 and a tie for that honor in 1955. The 1950s and early 1960s were years of triumph for other coaches and teams that later became Penn State legends. In nearly all sports during these years, the University recorded more wins than losses. In wrestling (coached by Charlie Speidel), gymnastics (under Gene Wettstone), and track (under Charles "Chick" Werner), it posted some particularly outstanding seasons and gained national honors. Nationwide recognition was more elusive in basketball (coached by Elmer Gross and John Egli) and baseball (under Joe Bedenk), but in both sports Penn State was a successful regional competitor, and basketball especially remained popular with students.

Women's athletics was for many years limited to intramural contests and physical education classes, as in these views ( top row) of tennis (left), field hockey (center), and basketball (right). Men's athletics, by contrast, featured many intervarsity programs, as demonstrated by this photographic sampling of it offerings: (second row, left) lacrosse, 1958; (right) wrestling, 1965; (third row, left) basketball, 1955—number 22 is Jesse Arnelle, one of the Lions' all-time scoring greats and later a University trustee; (center) Olympic gymnastics tryouts at Recreation Hall, 1956; (right) passing the baton—a 1965 track meet at Beaver Stadium; (bottom row, left) soccer, 1965; (right) baseball, 1965.

Intramurals were also a conspicuous feature of the Penn State athletic scene. Dean McCoy placed a high value on intramural sports, and the University maintained its tradition of having a varied, well-organized recreational program. Until his retirement in 1959, Gene Bischoff arranged schedules, kept records, and saw that playing equipment and space were made available for intramurals, just as he had done since the days of Hugo Bezdek's directorship of physical education. Women, lacking the opportunity to compete in intercollegiate athletics, participated extensively in intramurals through the Women's Recreational Association. By the early 1960s, over 1,600 coeds annually were playing softball, field hockey, tennis, volleyball, and other W. R. A. -sponsored sports. These activities were separate from the women's physical education program and did not involve competing against male intramural teams, although informal contests were occasionally scheduled with women's teams from Lock Haven, Bucknell, and other nearby colleges and universities.

But by nearly every standard, intercollegiate football reigned supreme in Penn State athletics, and with good reason. The only sport to generate a large following, year after year, among alumni and the public at large, it was an economically profitable enterprise. The large surpluses accruing from football made up for deficits elsewhere in the athletic budget and assured the survival of those varsity sports that appealed mainly to students and could never hope to pay their own way.

Football was also the medium through which millions of Americans became acquainted with Penn State, as the University began to compete regularly against schools that were longstanding national football powers. Appearances oil national television networks began in 1958. The Nittany Lions made their second trip to a post-season bowl a year later, when they played in Philadelphia in the first annual Liberty Bowl. A second trip to the Liberty Bowl in 1960 was followed by two consecutive trips to the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida. All four bowls received national television and press coverage, and the Gator Bowl appearances in particular were financially worthwhile. (Promoters of the Liberty Bowl encountered difficulty In drawing large crowds and later moved the contest to Memphis, Tennessee.)

When President Walker said that Penn State should have a great football team in addition to a lot of buildings and a distinguished faculty, he was to be taken seriously. To his way of thinking, it made sense for the University to excel in football, so long as academic goals were not compromised. He and Milton Eisenhower had rejected Ralph Hetzel's philosophy that a heavily subsidized and publicized program of intercollegiate athletics, with football as its showpiece, was incompatible with the scholarly purpose of an institution of higher learning or with the noble "athletics for all" ideal of intramurals.

Eric Walker committed the University to build on the foundation that had already been laid for the football program. By the third year of his presidency the value of athletic scholarships and grants-in-aid reached $135,000, or about 15 percent of all financial assistance given to undergraduates. Much of that sum came from the Levi Lamb fund, named in honor of a Nittany Lion football player who had lost his life in World War 1. Dean McCoy had established the fund in 1953 to receive athletic aid given by alumni. At the end of the 1959 season, Beaver Field (or New Beaver Field, according to purists) was dismantled w Beaver Field, according to purists) was dismantled and moved to the eastern periphery of the campus. The relocation made way for more academic buildings on the central campus and also provided another opportunity to increase seating capacity. When Beaver Stadium opened for the 1960 season, it could accommodate over 46,000 persons, making it the largest all-steel collegiate stadium in the nation. If Penn State was not yet a big-time football school, all signs clearly indicated that it soon would be.

The Not Necessarily "Silent Generation"

Students attending college during the 1950s and early 1960s have often been collectively labeled "the silent generation." They were alleged to have little interest In serious political or social issues, desiring only to lead secure, tranquil lives. They possessed enough ambition to pursue the American dream-a good job, a house in the suburbs, two or three children, perhaps a country club membership-but had no inclination to leave their own unique imprint on society. They supposedly had no quarrel with authority and indeed hoped to become influential members of the social establishment themselves as soon as possible. Male undergraduates, plodding earnestly to and from classes in jackets and ties, already seemed to be climbing the corporate ladder. Coeds, it was said, came to college to find husbands rather than to prepare for life-long professional careers. Various sociological explanations were offered to account for these attitudes. Students were characterized as reacting to the paranoia of McCarthyism; they were anxiety-ridden by fears of a nuclear war; they wanted to avoid at all costs the insecurities their parents had known during the Great Depression.

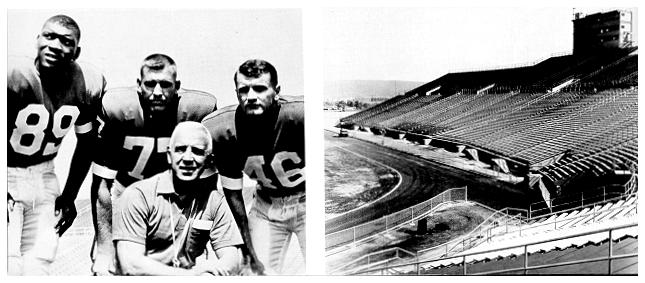

(left) Rip Engle with players from the 1962 Gator Bowl squad (from left): Dave Robinson, Chuck Sieminski, and Roger Kochman. (right) Finishing touches are applied to the "new" Beaver Stadium, 1960.

Students of the 1950s and early 1960s undeniably were docile compared with the veteranladen student body that had preceded them, but that immediate post-war generation of undergraduates was an aberration. The generation of the 1950s, at Penn State at least, bore a remarkable resemblance to past student bodies and was not especially unique. Students rarely questioned the wisdom of their professors. They appeared content to let a few administrators in Old Main make the decisions that really counted in their academic lives, They did not seem more or less concerned than their predecessors about important national and international issues.

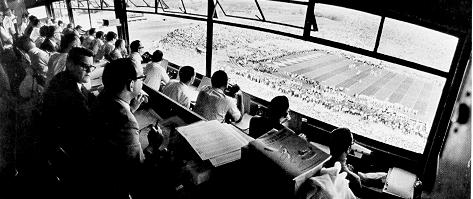

Press box perspective of one of the first games to be played at the stadium.

Daily Collegian editorials of the 1950s, for instance, typically admonished students to stay on the sidewalks and refrain from walking on the grass, and urged political leaders to keep the voting age at 21 on the grounds that even college sophomores and juniors were not mature enough to participate in the electoral process. Neither the Collegian nor any other organized student voice had much to say about such controversial topics as American intervention in Korea, the Russian invasion of Hungary, or the missile gap that John F. Kennedy said made the U.S. vulnerable to Soviet aggression. A professor who taught in the Department of Journalism during the 1950s recalled that undergraduates of that era "were indeed a generation without burning causes or even political commitments, whose call to action was the panty raid, rather than an ideological demonstration." That is an accurate enough statement, yet he was wrong in implying that it characterized students of that era only. Substitute something like "class scrap" or "the Pitt game" for "panty raid," and the description could apply to all previous generations of Penn State students.

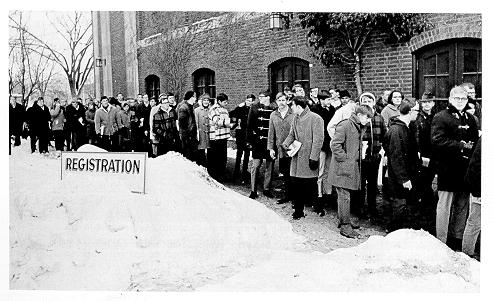

The ubiquitous Penn State line. In this case, students are queuing up for arena registration at the Recreation Building.

The truth was that silent generation or not, most basic elements of student life at the University did not change much over the years. Two things remained uppermost in the minds of undergraduates: preparing for future employment, and having as much fun as possible while doing so. Then there were the usual gripes that by the 1950s had become a standard feature of campus living. Students residing on campus despaired over waiting in long lines at the dining halls: Could not the University stage an event so simple as lunch without making students queue up for interminable periods? Another practice detested by undergraduates was the overfilling of residence halls at the start of every school year. The University purposely overbooked so that, after taking into account early withdrawals, the dormitories would operate at or near full capacity (and income) for most of the year. Many students were forced to spend weeks or even months living in study lounges or with extra roommates. Compulsory ROTC was also a favorite target for abuse, but not on ideological grounds; students merely found it a nuisance. Complaints were not limited to the campus. Sunday movies were finally approved by State College voters in 1955, only to prompt student complaints that the theaters were not air conditioned. Students were also dissatisfied with downtown bookstores and wanted a non-profit cooperative store that sold new and used books and a comprehensive line of stationery items.

The infamous "ratio" was still complicating relations between the sexes. Penn State coeds of the 1950s and early 1960s did nothing to tarnish their long-held reputation for being extremely discerning (some males used other adjectives) in their choice of dates. They could well afford to be discerning; for the women who went to college to find husbands, Penn State was surely a happy hunting ground. Men, naturally, were not so enthusiastic about the situation. "If you subtract the ugly girls and the ones the fraternity guys were dating," remembered a male dorm dweller, "the chances were more like one in a hundred that a guy from Pollock would have a date." "By Monday, every self-respecting coed on the campus had dates lined up for the weekend to follow," recalled a graduate of the class of '57. "If she didn't, she wasn't about to admit it to some clod who had the brass to call her as late as Tuesday evening. She'd rather stay in on Saturday night. By Wednesday, she wouldn't even answer the phone!" Homecoming in October and a few other big weekends sprinkled throughout the year offered the only relief from the ratio. On these occasions, "imports" rolled in by the bus load in scenes reminiscent of the house party weekends of the 1920s. Many a popular coed who delighted in the attention usually lavished on her by a swarm of males spent these weekends playing bridge with her roommates.

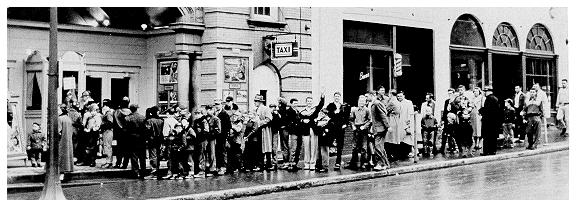

State College's first Sunday movie, in December 1955, produced this line at the Nittany (later Garden) Theater. The feature: Walt Disney's African Lion.

Dean of Women Pearl Weston did her best to make sure that the social lives of Penn State females remained as wholesome as ever. Throughout most of the 1950s, women had to plan their nonacademic activities around a residence hall curfew of 10:00 P.M. weeknights and 1:00 A.M. weekends. (Freshmen hours were more restricted.) Before leaving on weekend evenings, women still had to go through the customary signing-out procedures, indicating their destination and when they would return. Signing in was also mandatory. Men were not allowed beyond the lobby, and even there, hours were limited. Housemothers ("hostesses" in Penn State parlance) saw that these and other rules governing the social conduct of women were obeyed. Curfew was extended for the occasional festive weekend of the social calendar, but Dean Weston refused to let these exceptions become the norm, in spite of repeated protests by both men and women.

Weston believed that parents had to be assured that their daughter's personal development was as important to the University as her academic progress. Anything that might lower the standards of either was to be avoided. When Bermuda shorts and jeans became fashionable in the early 1950s, women were prohibited from wearing them primarily because the dean regarded them as improper dress in academic surroundings. In 1954, the Women's Student Government Association secured a partial lifting of the ban; coeds were allowed to wear shorts and jeans when participating in sporting events and while attending off-campus social events such as picnics and hayrides. They were still not approved for wearing to class, in dining halls, or for lounging around residence hall lobbies.

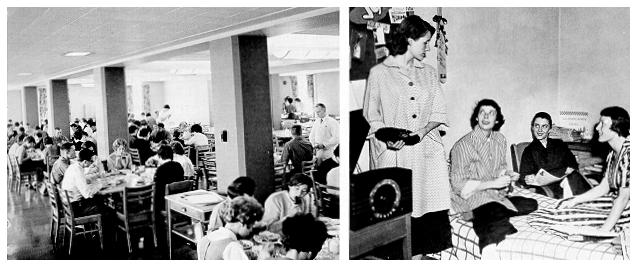

A dining room in Simmons Hall and a women's residence in McElwain.

In 1957, Dean Weston issued a series of rules designed to improve the manners of young ladies at mealtimes. Most of these rules involved matters of common sense (Rule No. 5: "Don't slouch in your seat") and etiquette (Rule No. 6: "Don't play with the silver") that presumably students had learned at home as children. (Rule No. 10: "Don't push your plate back when you are finished. You must simply place your knife and fork at the four o'clock position on your plate.") However well intentioned, these regulations became the butt of endless ridicule, and coeds chafed more than ever under what they considered to be childish restrictions.

Perhaps the most insidious threat to coed morals, in the eyes of Dean Weston, came from the panty raid, a widespread phenomenon on college campuses in the 1950s. Penn State's first and largest panty raid occurred on April 8, 1952. More than 2,000 undergraduate males marched on McAllister, Atherton, Simmons, and McElwain halls demanding lingerie. Many women gladly participated in this rite of spring, throwing all sorts of intimate apparel to the men and urging them to break into the residence halls. Coeds in Atherton Hall opened doors and windows just as fast as the hostesses could shut and lock them. Representatives from the offices of the dean of men and the dean of women finally quelled the disturbance by threatening severe disciplinary action. The incident was mild compared to those on some campuses, where near riot conditions prevailed and police had to be summoned. At more than one school, frenzied men carried away as their trophies not only panties but the women who were still wearing them.

Another aspect of student life that changed little was the continuing decline of interest in freshman customs. Beginning in 1954, freshmen of both sexes wore blue dinks and cardboard name tags. But these and other customs requirements were not enforced with regularity. Upperclassmen and freshmen alike increasingly regarded customs as juvenile and humiliating. Dink wearing, carrying the freshman handbook, restrictions on dating, and other elements of customs either faded away or were modified to become elements of orientation week. Introduced in 1964, this was the week preceding the beginning of classes in September during which upperclassmen volunteers attempted to familiarize freshmen with the workings of the University in a more friendly and relaxed style.

A final important constant in student life was the relationship with the off-campus community. While relations between town and gown were generally good, there were enough points of friction to maintain the usual tension between the two sides. Disturbances of the peace by overzealous undergraduates still occurred, for even the silent generation had to blow off steam occasionally. The worst incident occurred in May 1958 during the final examination period. A mostly male audience in the Cathaum Theatre on West College Avenue became disorderly during the midnight show, which the theater management finally suspended. The angry crowd, its boldness intensified by alcohol, then poured into the streets, smashing windows, breaking street lights, denting automobile fenders, and otherwise venting its ugliness. Borough police, representatives from the dean of men's office, and eventually state police were brought in to disperse the mob. Two policemen were injured and several students were expelled or suspended.

A time-honored ritual of fall semester: Mom and Dad help with the moving in.