Penn State's development during the 1960s was not confined to University Park. Growth at the branch campuses was as spectacular as that of the main campus. This expansion was not without controversy, however, as it coincided with the revival of Pennsylvania's long-dormant community college movement. In addition, Penn State took a giant step forward in professional education and public service by establishing a medical school and teaching hospital at Hershey, near Harrisburg.

The Commonwealth Campuses

Enrollments at the branch campuses had been climbing since the associate degree programs were introduced in 1953. Toward the end of the decade, these campuses were reorganized to prepare them to cope more effectively with the heavier demands expected in the 1960s and beyond. Under a plan formulated by Kenneth Holderman (on leave from his post as head of engineering extension) and approved by the trustees in 1959, the branches were more closely integrated into the academic mainstream of the University. They were detached from General Extension (itself reorganized into Continuing Education) and placed under a central coordinator (Holderman) who reported directly to the president. At the same time, many responsibilities were shifted from campus administrative officers to the academic colleges. In practice, for example, campus directors had always recruited faculty. Now deans and department heads had that job. These and other measures were taken to decrease the isolation felt by many branch campus personnel and give them a greater opportunity to participate in the general affairs of the institution. To symbolize the reorganization, the network of branch campuses was henceforth known as the Commonwealth Campus system. (The term "Commonwealth Campus" referred only to those branches whose physical plants met certain criteria, including ownership of the property by the University. Those that rented or leased facilities were still called "centers.")

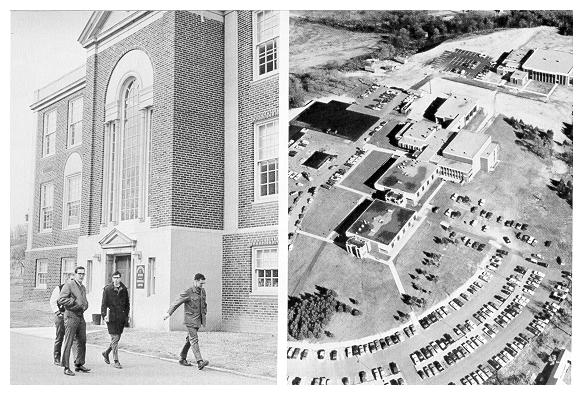

Dubois McKeesport

By 1959-60, 1,600 associate degree students and 2,100 undergraduates were attending classes at fourteen locations. Only associate degree studies and continuing education classes were available at Allentown, Berks, New Kensington, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, and York. Offering lower level baccalaureate work as well were campuses at Altoona, Behrend, DuBois, Hazleton, McKeesport, Ogontz, Pottsville, and (in forestry) Mont Alto.

McKeesport was the only campus to receive an undergraduate curriculum during the 1950s. Founded as a technical institute after World War II, it did not have sufficient space to meet the community's request for baccalaureate work until 1956, when local realtor and philanthropist William L. Buck donated ten acres of land as the site for a new campus. A fund drive was organized, two new buildings were erected, and undergraduate instruction began in 1959.

The demand for higher education was growing at a rate that surpassed previous predictions, and the Commonwealth Campus system was expected to bear much of the burden of this growth. More campuses had to be upgraded to baccalaureate work, until at least 10,000 students could be accommodated by 1970. Shifting a greater proportion of the incoming students to the Commonwealth Campuses would relieve pressure on facilities at University Park, where more attention could be given to specialized instruction for upper-level undergraduates and graduate students. Adding freshman and sophomore curriculums to more branch campuses would also make education less expensive for students, most of whom could commute to class.

As the goals for the Commonwealth Campuses were being set, changes in fiscal policy were also being instituted. When they approved the formation of the Commonwealth Campus system, the trustees dropped the provision that the branches had to be financially self-sustaining. That provision had been a source of unhappiness among personnel at the old centers, if only because it had often meant higher student fees. Now a uniform schedule of charges was introduced, with tuition slightly lower than that at University Park, and more of the University's financial resources made available for Commonwealth Campus development. The University began applying for GSA funds for the branch campuses, something it had not done in the past for fear of decreasing construction monies available to the main campus. Before 1960, nearly all building funds for the centers had to be raised locally. At the Altoona Campus, 3,000 donors contributed $400,000 in 1956 to build a combination classroom, laboratory, and administration building. A few years later, citizens of the DuBois area gave over a half million dollars to build a classroom-laboratory structure for their campus. These and similar campaigns in other communities raised substantial amounts of money and reflected the pride that citizens took in their local campuses, but they could not support the kind of expansion the Walker administration had in mind; GSA assistance was essential.

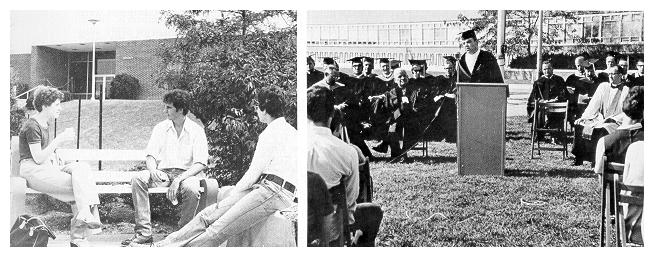

Ogontz Altoona

The University's revised policy of placing more emphasis on branch campuses initially attracted little public notice. That situation began to change after the General Assembly passed the Community College Act of 1963. Under this legislation, the Commonwealth pledged to pay one-half of the construction costs and one-third of the annual operating costs of these new, locally organized institutions. The Community College Act represented at least a partial fulfillment of an idea first advanced by Governor Leader for low-cost higher education. It also touched off a war that was to last for the remainder of the decade between proponents of the community colleges and supporters of the Commonwealth Campuses.

Following the passage of the act, the new Council of Higher Education was directed to formulate a master plan for Pennsylvania's educational future that would, among other things, delineate the place of these two-year institutions. The council would base its plan on information provided by a number of specialized studies. To study the role of the community colleges, it retained the consulting firm of Ralph R. Fields and Associates.

While that study was being prepared, the council held public hearings on the proposed master plan and the place of community colleges in it. Witnesses testifying on behalf of the community college idea claimed that branch campuses of large universities hindered the growth of an extensive system of independent two-year schools. (Ralph Hetzel held this opinion thirty years earlier, it will be recalled, when he reluctantly established Penn State's first undergraduate centers.) The Commonwealth Campuses comprised the chief obstacle, but the University of Pittsburgh's undergraduate centers at Johnstown, Greensburg, Bradford, and Titusville were also seen as stumbling blocks. Pennsylvania would continue to lag behind other states in community college development so long as these branch campuses were allowed to proliferate.

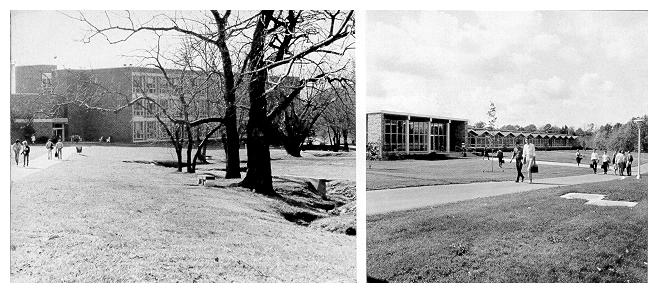

Mont Alto Shenango

Why was it in Pennsylvania's best interests to have a strong community college network? Among the arguments most often heard were the low costs and local control that were associated with these institutions. Community colleges did not need the expensive laboratory equipment and high-priced professors found in four-year schools and consequently could keep tuition and other costs down. And as institutions that were organized and governed by local residents, community colleges were said to be more sensitive to local needs than were branch campuses administered by a distant university.

Eric Walker and Kenneth Holderman defended the branch campus concept at these hearings. Speaking before the Council of Higher Education in February 1965, Walker affirmed that there was ample room for both community colleges and Commonwealth Campuses in Pennsylvania. The two years of instruction at a Commonwealth Campus were part of a baccalaureate curriculum designed to be completed at University Park, whereas a community college's curriculum was usually terminal. Students finishing their studies at a community college and then transferring to a four-year institution often had to take more course work than expected and required more than two additional years to obtain their bachelor's degrees. This was especially true in the scientific and technical fields, where community colleges did not possess well-equipped laboratories or qualified personnel. Admittedly, the associate degree programs were terminal in nature; but Walker contended that these offered a higher level of professionalism than the few comparable programs available at community colleges, which tended to be more vocationally oriented.

In sum, Walker and Holderman told council members, community colleges and Commonwealth Campuses operated according to different philosophies and catered to different types of students. Commonwealth Campuses, on the one hand, had curriculums for students interested in science and engineering that could not be easily duplicated by two-year schools. Community colleges, on the other hand, were ideal for students who were pursuing nontechnical studies or who had not firmly decided upon a career choice. Furthermore, Penn State's admissions standards were high as compared to those of community colleges, which historically-as part of their reason for being-accepted all students from their geographic service areas who met minimum qualifications.

Fayette Beaver

The battle between community colleges and Commonwealth Campuses was soon being fought across the state by politicians, educators, and civic leaders. Which groups embraced which cause varied from one region to another, although generally speaking, persons involved with secondary education were more enthusiastic about community colleges than higher-education personnel. Critics of the Commonwealth Campuses maintained that in spite of having local advisory boards, each branch ultimately yielded to University Park in important policy matters. Defenders retorted by declaring that there could be no such creature as a locally governed community college. The state was prepared to spend large sums of money to build and operate these institutions, and state control would inevitably follow. And how could community colleges generate more local support than that already given to the Commonwealth Campuses, as evidenced by the numerous successful fund drives? Claims and counterclaims continued without end.

At the February hearings, President Walker had stated unequivocally that since the Commonwealth Campuses were performing a valuable service, the University would not curb their growth merely to permit the establishment of more community colleges. It had already added undergraduate studies at Mont Alto in 1963 (in addition to forestry) and New Kensington in 1964. In January 1965, the board of trustees had approved the creation of three brand new campuses in western Pennsylvania. They were to serve Beaver and Fayette counties and the Shenango Valley (Sharon) area.

Although not legally required to do so, the trustees submitted plans for the new campuses to the State Board of Education for its approval, which was soon forthcoming. The board's vote was not unanimous, however; several members, undeterred by the fact that the initiative for all three campuses had come from local business and government leaders, accused Penn State of deliberately attempting to sabotage the community college system. Approval of the new branches would make organizing community colleges in those areas extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Schuylkill New Kensington

The trustees were not dissuaded, and the development of the campuses proceeded at a rapid pace. The Beaver Campus was at first confined to a former county hospital annex in Monaca, across the Ohio River from the community of Beaver. The county commissioners donated the building, paid for its remodeling, and voted to allocate $600,000 toward construction of more buildings on an expanded site. Work on the new facility began in 1967, and the first of several new buildings was opened a year later.

In Fayette County, the Commonwealth Campus took the place of an undergraduate center operated by Waynesburg College (of Washington, Pennsylvania). Waynesburg College officials were the first to suggest that a Penn State branch be established. They considered further operation of their own center economically unfeasible but did not wish to leave the area without direct access to higher education. Community leaders seconded the proposal and eventually $1.2 million was raised to help pay development costs. Temporary quarters were obtained in Uniontown, pending completion of new buildings on a permanent site between Uniontown and Connellsville, which had also expressed interest in having a branch campus. The first of these buildings was opened for classes in the fall of 1968.

The Shenango Valley Campus was expected to serve all of Mercer County and parts of five others. The supporters of this campus were exceedingly thorough in their efforts to obtain higher education facilities for their community. In 1964, a committee of civic leaders was formed to solicit proposals for a branch campus from Penn State, the University of Pittsburgh, and Edinboro State College. The committee found Penn State's offer to be the most satisfactory but feared that the State Board of Education would try to block it. Nearly 10,000 Shenango Valley residents subsequently signed petitions asking the University to establish a campus in the Sharon area. The petitions were then presented to the board as proof of grass roots enthusiasm for the venture. The Shenango Valley Campus had its quarters in a new but temporarily vacant Catholic high school in Sharon. A permanent 11-acre site that included a renovated Junior high school building was acquired in the downtown area in 1967. Local contributions of $200,000 helped to finance the construction of a new science building in 1968.

Building construction at all three of the new campuses was aided not only by local and GSA funds, but also by federal grants. In 1965 Congress enacted legislation that enabled the federal government to match, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, capital funds raised locally and through state agencies. The Higher Education Facilities Act was to have a profound impact on the future physical growth of the Commonwealth Campus system.

That system expanded in spite of the conclusions contained in the study that Fields and Associates did for the Council of Higher Education. Completed in June 1965, the report did not become controversial until the council embodied its recommendations in the new master plan, adopted in September 1966. The council called for a halt to the opening of new branch campuses and the conversion of existing ones to community colleges wherever feasible. (Thus far, only five new institutions had been established under the Community College Act.)

York Capitol Campus, first academic convocation, Oct. 1967

President Walker publicly criticized the Fields consultants for, in his estimation, examining only the prospective role of the community colleges and ignoring the past performance and future role of the Commonwealth Campuses. According to Walker, the consultants proceeded under the false assumption that community colleges were inherently more advantageous for Pennsylvania than branch campuses. Therefore, their findings consisted mainly of suggestions on how to establish these institutions rather than whether they should be established in the first place.

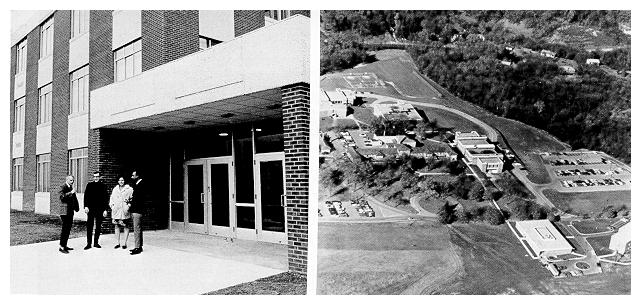

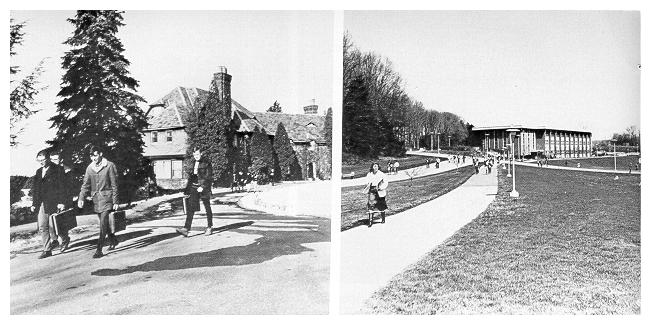

The Worthington Scranton Campus: (left) President Walker, in the center of this picture, with campus director Robert E. Dawson and Governor William W. Scranton to his left, at the ground-breaking ceremony in 1966; (right) an aerial view of the campus.

In testimony before the state House of Representatives' subcommittee on higher education in October 1966, Walker cited figures to show that by almost any academic standard of comparison, the Commonwealth Campus system compared favorably with the community college systems of other states-even California, which Fields had said Pennsylvania should emulate. Nor were there any significant differences in grade point averages between Penn State graduates who had spent their first two years at a Commonwealth Campus and those who had attended University Park for four years. The Commonwealth Campuses were not offering second-rate education, Walker asserted. They were giving good service, and the citizens of the state supported them. Why was any change necessary? Walker's testimony appeared to reflect a subtle change in attitude. Instead of emphasizing that Commonwealth Campuses and community colleges could coexist, he seemed to be indicating that the Commonwealth Campuses were already fulfilling most of the functions of community colleges.

Astute politician that he was, Governor Scranton refused to take a public stand on the issue. Replying to a reporter's question about the future of Commonwealth Campuses in the wake of the Fields study, he replied, "There are enough of them, or almost enough." Privately, Scranton was inclined to be sympathetic toward Penn State. In October 1965, he had selected J. Ralph Rackley, the University's Vice President for Resident Education, to be Superintendent of Public Instruction. (The Department of Public Instruction was the administrative arm of the State Board of Education.) This appointment was interpreted by Penn State's friends and foes alike as a tacit sign of support for the institution's general policies. A few months later, the governor removed Charles Simpson as head of the Council of Higher Education, ostensibly after a dispute involving matters unrelated to Penn State. Simpson (president of the Philadelphia Gas Company) was an outspoken critic of the University. He had been one of the first to compare the institution to an octopus, greedily spreading its tentacles into all parts of the state.

Not only did the Scranton administration not oppose the growth of more Penn State campuses, it was actually the driving force behind the founding of one of them. In 1965, the Department of Defense announced its intention to close Olmstead Air Force Base, located near Middletown, a few miles south of Harrisburg. The base was one of the area's largest employers, so local and state officials began to explore other uses for the installation once it had been phased out. Governor Scranton, after consulting with state Commerce Secretary Clifford Jones and the Harrisburg Chamber of Commerce, asked Eric Walker if the University could use a portion of Olmstead as a center for graduate education. The curriculum could be geared to the region's economy, with courses offered especially for teachers, public administrators, journalists, and engineers.

Delaware Behrend

The Walker administration accepted the governor's proposal and recommended that upper-level undergraduate work be offered in addition to graduate studies so that more efficient utilization could be made of the faculty and physical plant. Undergraduate instruction would also fill a large void, for although Harrisburg was Pennsylvania's sixth largest city, it had no four-year college within its boundaries. Middletown was not within the city limits either, but a Penn State campus there would be closer than any other four-year school. It would also be readily accessible to the capital's metropolitan population of 350,000. The University trustees gave their formal approval to the new campus-to be known as the Capitol Campus-in January 1966. Coleman Herpel, former director of the Ogontz Campus and a longtime branch campus administrator, was named director.

Penn State was no stranger to Harrisburg, having operated an undergraduate center there for a few years after World War II and having been a partner in the Harrisburg Area Center for Higher Education. In the early 1960s, University officials had considered requests from area civic leaders to establish a Commonwealth Campus in the state capital until local interest wane after the founding of the Harrisburg Area Community College, the first institution to open its doors under the Community College Act.

Governor Scranton secured a legislative appropriation to convert Olmstead for educational use in the spring of 1966. Token classes began that fall. The three-story administration building and the numerous other structures needed extensive remodeling, and not until the fall of 1967 (by which time the Air Force had withdrawn) was the first full-size class admitted. The Capitol Campus enjoyed a good deal of operational independence and received encouragement from the Walker administration to experiment in curricular development. Baccalaureate programs in engineering technology and American studies were among the earliest innovations.

The Capitol Campus complemented rather than competed with the Harrisburg Area Community College and other two-year schools. It was the only institution in Pennsylvania to admit all graduates of any accredited community college with full junior standing. By 1969-70, one-half of Capitol's 1,300 undergraduates had come from these colleges; most of the rest came from Commonwealth Campuses. In either case, students had already received their general education and had transferred to Capitol for specialized instruction. It was a unique arrangement.

Hazleton Berks

In a final show of confidence in the University, Governor Scranton endorsed President Walker's request that a new study be made of the Commonwealth Campuses in the context of Pennsylvania's overall educational needs. The State Board of Education agreed and retained Heald, Hobeson and Associates of New York to make the survey. In the meantime, the development of the Commonwealth Campuses continued and included the founding of new campuses, the addition of baccalaureate studies to others, and the general upgrading of the physical plants.

The campus at New Kensington had outgrown two public-school buildings since its establishment as a center for associate degree work in 1958. In 1966, a new and permanent campus was occupied on land donated by Alcoa, a major industry in the community. The local advisory board raised three-quarters of a million dollars as the community's share of the $3.5 million needed for the several new buildings that were planned for the campus. In January 1967, the Schuylkill Campus (formerly the Pottsville Center) moved from its crowded quarters in Pottsville to the former county home and sanitorium in Schuylkill Haven. The county commissioners had deeded the facility to Penn State several years earlier and had helped share the cost of its renovation. The University also acquired the federal government's former anthracite research laboratory, situated across the highway from the campus, and converted it to a women's residence hall.

Baccalaureate curriculums were added to the York, Scranton, and Berks campuses. The York Campus had begun as a technical institute in 1949. Four years later, associate degree studies were inaugurated and proved so successful that the campus was able to vacate its rented quarters in the public-school building and occupy a permanent site of its own in 1956. By popular request, undergraduate work was introduced in 1966 and more buildings were constructed within a few years.

The Scranton Campus, too, originated after World War II as a technical institute. While a number of four-year institutions were located in or near Scranton, none offered accredited curriculums in technological fields. Thus public support grew on behalf of adding baccalaureate studies at the Scranton Campus. Because lack of space at the in-town site made this impossible, the advisory board in the mid-1960s purchased a 45-acre tract in suburban Dunmore and established a building fund. The new facility was named the Worthington Scranton Campus in honor of Governor Scranton's father (whose forebears founded the city bearing the family name). Classes began there in the fall of 1968.

The Berks Campus traced its origin to the Wyomissing Trade School, founded in 1927 by the Textile Machine Works to give advanced practical and theoretical instruction to textile workers in the Reading area. The school was renamed the Wyomissing Polytechnic Institute in 1933, and its curriculum diversified. It continued to be run by the Textile Machine Works until its closing in 1958, when the facility was offered to Penn State. Designated the Wyomissing Center, it offered associate degree and continuing education studies until 1965, when a limited baccalaureate curriculum was begun. (By that time, too, the name had been changed to the Berks Center.) The facilities at the old Polytechnic Institute restricted further development, and in 1968 a million dollar fund drive was launched. A 104-acre tract (also in suburban Reading) was purchased in 1969 as the site of the new Berks Campus. Building construction got under way a year later.

The last new Commonwealth Campus to be founded in the 1960s and the one stirring the most controversy at the state level was in Delaware County. In 1966, the county commissioners invited the University to establish a cam-pus and promised to provide land plus at least $1 million for construction. The board of trustees accepted the offer in September of that year. The Delaware County Campus was to be located on a 100-acre tract near Media, where it would be able to serve the growing suburban population south of Philadelphia.

Plans called for classes to begin in temporary facilities in the city of Chester in the fall of 1967-the same time the new Delaware County Community College was scheduled to open. Both the Delaware Campus and the community college had strong advocates. The county commissioners and the county's representatives in the General Assembly asserted that the area needed both institutions, but the State Board of Education refused to put its seal of approval on the Commonwealth Campus. Since the board had no legal authority to dissuade Penn State, it adopted a resolution demanding that the legislature delete from the University's upcoming budget all funds designated for the development of the campus. The board noted that it had approved the establishment of the Delaware Valley Community College on the assumption that the region did not have a similar institution. It also pointed to the master plan's recommendation against building new Commonwealth Campuses.

University officials responded that Penn State had already given its word to the county commissioners and would go ahead with the project no matter what the General Assembly did. The legislators did not give serious consideration to the Board of Education's resolution. Development proceeded as scheduled, and the first building at the new campus was occupied in January 1970.

The argument over the Delaware Campus had subsided for the most part by the time the Heald, Hobeson report was released in March 1968. The document was the kind of detailed examination President Walker had wanted, but he found some of its conclusions highly unsatisfactory. The consultants praised the University for operating its branch campuses in an extraordinarily efficient manner. They nonetheless suggested fundamental changes in two categories, First, Heald, Hobeson pointed out that there was nothing in the land-grant mandate that required Penn State to offer "subprofessional" training, meaning the associate degree programs. That work should be transferred to community colleges.

Wilkes-Barre

Second, the consultants reiterated the Fields' study recommendations that no more Commonwealth Campuses be built and that some of the existing ones be converted to community colleges. The campuses at Altoona, DuBois, Fayette, Scranton, and York should become community colleges; Behrend, McKeesport, and Hazleton should be reorganized as independent baccalaureate institutions. Consolidation or elimination was recommended for several of the other campuses until just five (Beaver, Mont Alto, New Kensington, Shenango Valley, and Wilkes-Barre) remained in their original form. Similar scenarios were proposed for the satellite campuses operated by the University of Pittsburgh and Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

The Heald, Hobeson report deeply disturbed University administrators. The associate degree program had been extremely successful. It was one of the largest (as well as the first) of its kind in the nation; employers regularly testified to the competency of its graduates. Kenneth Holderman had won the highest recognition from the American Society for Engineering Education (the James H. McGraw award) for his role in developing and administering the program. Why should it be transferred to the supervision of community colleges? The same question was asked about the baccalaureate curriculums of the Commonwealth Campuses, which by the consultants' own admission were doing the jobs they were supposed to be doing.

The local advisory boards were up in arms over the Heald, Hobeson report, and communities having Commonwealth Campuses likewise reacted negatively for the most part. A DuBois Courier Express editorial of April 26, 1968, typified local feeling. The editors urged the State Board of Education not to implement the report's recommendations. "Our advice to the State Board of Education," said the paper, "is don't foul up a good thing. The Commonwealth Campus system works so well, produces such fine products, and indeed serves as such a vital element in future university planning that eliminating them would be a crime in Pennsylvania, where more, not fewer, facilities are needed." A strong defense of the campuses by local citizens could not be casually dismissed, for these were the same citizens who would have to pay the additional taxes that new community colleges were likely to bring.

Members of the General Assembly and Governor Shafer were aware of that fact. The State Board of Education tended to look favorably on the consultants' recommendations, but it was powerless to enact them into law. As far as converting the branch campuses of Penn State or any other institution into community colleges was concerned, the Heald, Hobeson report had little immediate impact.

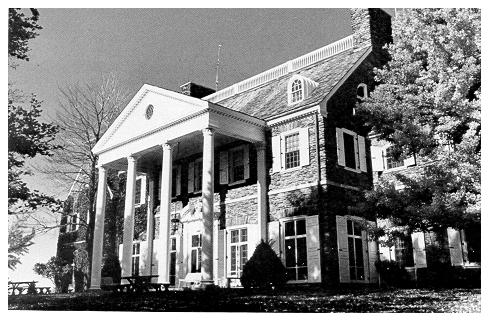

Nor did the report appear to have much influence on the University's plans to make further improvements at the campuses. Two more, Wilkes-Barre and Allentown, received approval from the trustees to introduce lower-division baccalaureate courses. Wilkes-Barre had long been a location for technical institutes and later associate degree work. Classroom and office space had always been rented, however. In the early 1960s, Penn State officials considered merging instruction with the Scranton Campus and acquiring a new campus between the two cities. Enough citizens complained to put an end to that idea, but a permanent site still had to be found. In 1964, Mr. and Mrs. Richard I. Robinson of Greenwich, Connecticut, donated the 48-acre estate of Mrs. Robinson's late uncle, coal magnate John Conyngham, to the University for a new Wilkes-Barre Campus. The gift, valued at $1 million, included a 50-room mansion ("Hayfield House") and 19-car garage. It was situated near Dallas, about five miles from downtown Wilkes-Barre. Local contributions underwrote most of the remodeling costs and the site was occupied in 1968. Undergraduate instruction began two years later.

Allentown was the site of Penn State's first permanent technical center, and classes had been held there continuously since 1912. Enrollments at Allentown were generally smaller than those of other Commonwealth Campuses, consisting only of continuing education and associate degree students. Still, facilities in a former cigar factory on Ridge Avenue and in nearby public schools were becoming inadequate. Some businessmen and civic leaders, including the Allentown Chamber of Commerce, advocated moving to a new and larger campus where baccalaureate studies could be begun. But the Heald, Hobeson report said the campus should be phased out because it duplicated the work of two community colleges and several four-year institutions in the Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton area. Most of these schools were against any expansion of the Allentown Campus and would have been pleased to see it closed altogether.

Therefore, when Mohr Orchards in 1968 offered 40 acres of land near Foglesville, west of Allentown, as a gift for a new campus location, University officials proceeded cautiously with its development. The land was accepted but not immediately developed, pending the reaching of an understanding between Penn State and neighboring colleges. In the interim, quarters were rented in the Fogelsville public school (one and a half miles from the Mohr tract) and limited undergraduate instruction began in 1970.

The University had more definite plans for the Behrend Campus, which experienced a steady growth in enrollment and physical plant throughout the 1960s. Erie had other institutions of higher education, but none offered accredited studies in engineering. That was one reason why the Heald, Hobeson consultants had suggested Behrend be converted into a four-year school. The consultants were not telling the Walker administration something that it had not been hearing for several years. Community pressure for curricular expansion was becoming impossible to ignore. In 1968, General Electric and several other large industrial employers convinced the University to launch a graduate program at Behrend leading to the master of engineering degree. The following year the board of trustees approved the addition of several four-year undergraduate curriculums. Behrend enjoyed much the same autonomy as the Capitol Campus. In 1973, its name was changed to the Behrend College of The Pennsylvania State University. Irvin Kochel, veteran (since 1954) director of the campus, continued as chief administrator. McKeesport and Hazleton were also considered for elevation to four-year campuses, but action was tabled until further studies could be made.

Behrend was not the first permanent site for off-campus graduate education. In 1963, the University established a graduate center at King of Prussia in the Philadelphia suburbs to meet the needs of engineers and other technical personnel employed in nearby business and industry. A curriculum culminating with the master of engineering degree was organized and a variety of workshops and seminars were also held regularly. In 1965, Penn State opened the Susquehanna Valley Graduate Center to satisfy a similar demand in the Harrisburg area. It was discontinued after the Capitol Campus opened.

By 1970-71, all of Penn State's Commonwealth Campuses, plus the Capitol Campus and what was to become Behrend College, offered continuing education and baccalaureate and (with the exception of Capitol) associate degree curriculums. These campuses accounted for nearly 40 percent of the University's full and part-time undergraduate population, distributed among 19 locations: Allentown, 40; Altoona, 1,245; Beaver, 1,160; Behrend, 1,270; Berks, 1,094; Capitol, 1,245; Delaware County, 647; DuBois, 425; Fayette, 815; Hazleton, 719; McKeesport, 1,169; Mont Alto, 434; New Kensington, 751; Ogontz, 1,468; Schuylkill, 771; Worthington Scranton, 577; Shenango Valley, 491; Wilkes-Barre, 87; and York, 445.

There can be little question that the Commonwealth Campuses at least partially duplicated services that community colleges could have offered, or that the Commonwealth Campuses retarded the growth of a community college system. However, the state government was slow to commit itself to that system. Consequently, Penn State (and to a lesser extent several other four-year institutions) had no alternative but to establish more branch campuses if Pennsylvania's educational needs were to be met. Similar outcomes occurred in Ohio, Wisconsin, South Carolina, Indiana, and several other states, where in the absence of strong initiative among governmental leaders for community colleges, large public universities took the lead in creating satellite campus networks similar to, if not so expansive as, Penn State's.

Whether or not the University should have modified its original plans for expansion once a community college movement did get under way is another matter. The important point is that the Commonwealth Campuses, together with the community colleges, met the burgeoning demand for higher education in the 1960s. They did what they were called upon to do. And in the case of the Commonwealth Campuses, it was the people who had called upon the University. While perhaps in some respects it did resemble an octopus, Penn State did not go anywhere it was not wanted in the 1960s any more than it had in the 1930s, as evidenced by the enthusiasm and generosity of the advisory boards, business and civic leaders, and ordinary citizens who did so much to establish and support the campuses in their own communities.

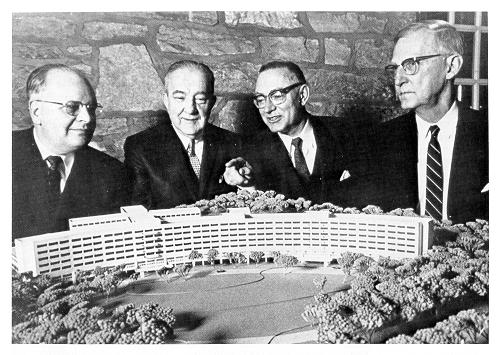

The founding fathers of the Hershey Medical Center (from left): Arthur Whiteman, president of the Hershey Trust Company; Samuel Hinkle; Eric Walker; amd George Harrell.

Proposed Professional Schools and the Hershey Medical Center

Amid popular appeals to launch more Commonwealth Campuses, the University also received numerous inquiries, especially from alumni and legislators, about founding law, veterinary, and medical schools. Law and medical schools were traditional hallmarks of a great institution of higher learning; and a school of veterinary medicine would be most appropriate, given Penn State's status as a land-grant school.

Calls for a veterinary school struck a responsive chord within Eric Walker. He envisioned Penn State producing veterinarians who specialized in farm animals, while the University of Pennsylvania trained veterinarians to work with domestic pets and exotic animals. Yet Walker initially took no substantive action, for two reasons. First, there was Milton Eisenhower's informal promise that Penn State would content itself with animal research and let Penn train veterinarians. Walker regarded that pledge as a more or less binding agreement between the two institutions. Then there was the matter of finances. Agricultural interests had long supported the idea of a school of veterinary medicine for Penn State. But even if these interests succeeded in raising enough money to organize the school, the University would still have to look to the General Assembly for operating funds. The farm bloc in Harrisburg was not as influential as it once had been, and President Walker did not see much enthusiasm among lawmakers for a second state-aided veterinary school.

The president was not impressed with the need for a law school, no matter how much prestige it might bring to Penn State. In 1957, a University study indicated that Pennsylvania's five law schools (Penn, Temple, Pitt, Duquesne, and Dickinson) were adequately meeting the demand for lawyers. What the Commonwealth seemed to require far more than additional lawyers were highly skilled professionals in science, engineering, and business management. Consequently, Penn State focused its attention on these areas rather than the law.

A decade later, the Walker administration reviewed the situation and concluded that the demand for lawyers was beginning to outrun the supply. The president then asked the University Senate's Committee on Academic Development to study the need for a law school and a school of veterinary medicine. In some quarters, there was a feeling that Penn State should have a law school if for no other reason than to Preserve institutional pride. Alumni and friends of the University were discomfited by the large numbers of Penn State graduates studying law at other schools within the Commonwealth, particularly at Temple and Pitt, both of which were now in the same state-related category as the land-grant institution. There was also the belief that if enough members of the General Assembly (which was dominated by lawyers) graduated from a Penn State law school, the University's political influence would increase measurably.

Early in 1969, the Senate committee reported that Penn State could make significant contributions to professional education by establishing both law and veterinary schools. The board of trustees then considered proposals for the schools but took no decisive action. This was a time of financial chaos in Harrisburg. To ask state government leaders to assist the University in expensive new endeavors did not seem wise.

In the early years of his administration, Eric Walker was no more impressed with the need for a medical school than a law school. The U.S. Surgeon General's Office reported in 1959 that the nation would need between 20 and 24 new medical schools within the next decade; but the demand for physicians would be greatest in states other than Pennsylvania, which already had a half-dozen highly respected medical schools. There was no logic in trying to convince the governor and legislature to support the establishment of a medical school whose graduates were likely to leave the Commonwealth. Moreover, medical schools historically were severe drains on the financial resources of affiliated universities. And assuming the state government did offer the University assistance in setting up such a school, the vast sums of money required to offer high-quality instruction to would-be physicians could seriously curtail institutional development in nonmedical areas. President Walker offered no encouragement to bills introduced in the General Assembly in 1961 and 1963 authorizing Penn State to start a medical school. Likewise, he resisted all offers to have the University affiliate with existing hospitals for the purpose of training physicians.

Then one day in March 1963, Walker's indifference was suddenly transformed into unabashed enthusiasm. The metamorphosis began with a telephone call to his office from Samuel Hinkle '22, president of the Hershey Chocolate Corporation and head of the philanthropic Hershey Foundation. Hinkle was well known to President Walker, having been active for years in alumni affairs and a recipient of the Distinguished Alumni Award in 1957. Walker was in Washington attending a conference, so Hinkle left a message saying that he would like to meet with him in Hershey just as soon as his business in the capital was finished. Not knowing what Hinkle wished to discuss and a little peeved at having to take time from his busy schedule "Just to humor old Sam," Walker nonetheless made the journey to Hershey.

There he met with Hinkle and several associates. "Eric, we've been wondering if Penn State is interested in starting a medical school," said the Hershey executive, getting to the heart of the matter at once. "Sam, save your breath," replied Walker. "You know there isn't a nickle in Harrisburg for that purpose." The University president then began to outline all the financial obstacles a medical school would encounter. "Well, if that's all you've got to say," snorted Hinkle, cutting Walker off in mid-sentence, "we've got the money. How much would it take?" After Walker quickly calculated that $50 million would do the job, Hinkle declared that that sum would be forthcoming from the Hershey Foundation. "You never saw eyes light and anybody drool like that in all your life!" recalled Gilbert Nurick, present as the Hershey interests' legal representative, of Walker's reaction. Hinkle had just made a university president's dream come true.

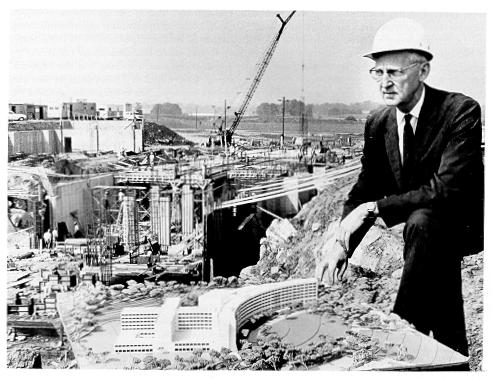

George Harrel contemplates a model of the Hershey Medical Center, while the real thing is under construction behind him.

The $50 million was to come via the foundation from the Hershey Trust Company, which was the financial trustee of the Milton S. Hershey School. The school had been founded in 1909 by Milton Hershey, who six years earlier had started the chocolate enterprise that also bore his name and that was to make him a millionaire many times over. It was an orphans' school, where homeless boys could get a sound education in a healthy environment. The school derived its income from the financial investments made by its trustee.

The problem was that after a half century of operation, the trust company was making far more money from its investments than could reasonably be spent on the school. The veritable fortune that was being amassed threatened to become a public embarrassment. The managers of the trust-who also constituted the managing boards of the foundation and the school began to search for another worthy charitable endeavor and eventually settled upon a medical school and teaching hospital. Pennsylvania's only such institutions were in its two largest cities. The University of Pittsburgh had a medical school, as did Temple and Penn, both of which were located in Philadelphia along with Jefferson, Hahnemann, and Women's medical colleges. The Hershey interests had no desire to become actively engaged in planning and administering the facility, however. Through Hinkle's efforts, that would be the responsibility of Penn State.

No immediate public disclosure of the Hershey gift was made because, under the terms by which it was created, the trust could not legally spend money on anything but the orphans' school. Approval from the Dauphin County Orphans' Court had to be obtained before any funds could be used for a medical school. In cases where money taken from a trust violated the purpose for which the trust had been created, the state attorney-general also had to be notified. In the opinion of University counsel Roy Wilkinson, Jr., Hershey attorney Nurick, and other legal consultants, a good possibility existed that Attorney-General Walter Alessandroni would intervene in court to block any transfer of funds. The Commonwealth was already contributing heavily to existing medical schools, and Penn State had not even made a study of the need for another one. It was merely accepting the word (and money) of the Hershey trust. How was the Commonwealth to know that the new medical school would not be an unnecessary financial burden?

President Walker then informally pledged that the University would seek no legislative appropriations for the school, and Alessandroni joined Penn State and the Hershey interests in petitioning the court to consent to the change in the trust. The petitioners also had to show that a medical school would be an appropriate recipient of Hershey Trust funds, and that the expenditure would not endanger the future welfare of the Milton S. Hershey School. The trust would be spending barely half the $96 million it had accumulated from a principal of $300 million. (President Walker later reflected that the managers of the Hershey Foundation probably would have been willing and able to give Penn State $60 million or $70 million, had he only asked for it on that fateful March day.) The court approved the petition in August 1963, and S50 million was transferred from the trust to the foundation.

Following the court's decision, official announcement of the gift was made and preliminary planning got under way. On August 27, 1964, University and Hershey Trust officials signed an agreement that formally transferred to Penn State the responsibility for designing and operating The Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Twenty million dollars would be spent on its construction, and $30 million was to be invested by the trust to create an endowment that would provide annual operating funds. The income from this endowment, along with federal and University funds, student and patient fees, and private gifts was deemed adequate to build and operate the center. The Hershey Trust would retain ownership of the facility and lease it to the University for one dollar a year. (In 1968, the University assumed full legal title to the center and the endowment in order to simplify legal arrangements. Under the original agreement, the University was placed in the awkward position of having to be the applicant for federal funds to build something it did not own. And in the event either Hershey of Penn State withdrew from the pact before the medical center was well along, a dispute could arise over which party had the responsibility to repay the federal government.)

The center was to be located in Derry Township, on the outskirts of Hershey. It was to include a medical school, a 350-bed teaching hospital, and facilities for medically related research and graduate programs. A site near University Park would have been in many ways more convenient, but there was doubt that rural central Pennsylvania could furnish a sufficient variety of clinical cases for the hospital. Nor could the University afford to overlook the wishes of its benefactors, who assumed the medical center would be as much a part of the Hershey community as the chocolate factory or the orphans' school, or the famous amusement park and hotel.

For administrative purposes, Hershey's students were enrolled in a new College of Medicine. Named dean of the college and director of the medical center in November 1964 was Dr. George T. Harrell. A graduate of Duke University's medical school and a nationally known medical educator, Harrell came to Hershey from the University of Florida, where he had overseen the founding of a college of medicine in 1954 and served as its dean ever since. He thus earned the distinction of being the first person to preside over the establishment of two modern American medical schools. Harrell's experience was invaluable, for a tremendous amount of planning and other work had to be done before the first class of students or the first patients could be admitted.

A general educational philosophy had to be formulated and the physical plant had to be designed. The academic and building plans then had to be submitted to a joint committee of the Association of American Medical Colleges and the American Medical Association, which in turn had to be satisfied that the medical center would meet accreditation standards by the time the first class graduated. Once the committee's preliminary approval was secured, application could be made to the federal government for matching construction funds. (More than $23 million was obtained.) Only then could a faculty and student body be recruited, a medical library be established, equipment purchased, and a host of other tasks undertaken.

Some curricular planning had been done by an advisory committee headed by psychology professor C. Ray Carpenter, but most of the work was left to Dean Harrell. He found that both the University administration and the Hershey interests gave him the free hand they had promised, although occasional differences of opinion did occur, even on the most fundamental of issues. "The concept of what a medical school was on the University Park campus, what it was in the Hershey community, and what the dean had as a concept of a medical school were often quite some distance apart," recalled Dr. Harrell. The community of Hershey had a small, obsolete hospital (the former infirmary of the Milton S. Hershey School). Hinkle and the other foundation managers thought of the medical school as a modern replacement for the old facility, with medical students trailing after physicians as they treated their patients. The Hershey interests did not grasp the necessity for a large amount of laboratory and classroom work, through which students acquired in-depth knowledge of the basic medical sciences, physiology, anatomy, biochemistry, pharmacology, microbiology, and pathology.

Administrators at University Park knew better. Courses in the basic sciences made up the first two years of study at virtually all medical schools. But they wanted the basic sciences to be a part of the scientific curriculum at the main campus and under the control of the appropriate departments there. Dean Harrell objected, arguing that the College of Medicine, because of its unique nature and location, should exercise authority over all phases of instruction. He got his way in the end. After convincing the Hershey group of the need for a strong basic science curriculum-, he won over the Walker administration to the idea that the college should be given as much autonomy as possible in graduate degree as well as M.D. programs.

The dean also ran into opposition with his request for an animal research farm. The Hershey managers were aghast that a million dollars should be spent on animal research facilities. President Walker was also uneasy, wondering if Harrell might have the farm in mind as an oblique way of getting a veterinary school. Harrell maintained that Hershey had to have a large animal research facility in order to attract faculty who were first-rate researchers. He eventually got the farm, although on a smaller scale than he had first proposed.

Once definite plans had been agreed upon, the medical center's development entered its brick-and-mortar phase. In February 1966, ground was broken in a snow-covered cornfield for a quarter-circular teaching building and the hospital. In September 1967, the first class of 40 students (chosen from 1,100 applicants) was admitted. The scene that greeted these students was not unlike the conditions found by the first undergraduates to arrive at The Farmers' High School more than a century earlier. The basic sciences wing of the medical sciences building was only partially finished, and work on the clinical sciences wing had just begun. The hospital was not yet even a hole in the ground. Building materials and construction equipment were scattered everywhere. Students had to live in converted residential dwellings nearby, pending completion of low-cost apartments.

The unfinished look gradually gave way to an air of completeness and permanency. On October 14, 1970, the teaching hospital admitted its first patients, and the Hershey Medical Center was essentially in full operation. It was the first such university-affiliated facility to be completed in Pennsylvania in the twentieth century.

What was more distinctive about the College of Medicine was the philosophy Harrell and his pioneering colleagues had instilled in it. Medicine was a science, but practicing it with a patient was an art. Physicians had to have some knowledge about their patients' values and social environments in addition to scientific data in order to treat or prevent illnesses. Their training should include humanistic concerns as well as traditional scientific disciplines. Hence, Penn State's College of Medicine became the first in the nation to have its own department of humanities, with courses in religion, philosophy and ethics, the history of science, and literature comprising an essential part of the medical student's curriculum. A few other university medical schools offered a smattering of instruction in the humanities (mainly ethics) but always under the supervision of faculty in the regular academic departments. Harrell insisted that the College of Medicine have its own humanities department so that instruction could be made relevant to the problem-solving orientation of medical students. He contended that liberal arts faculty who taught in a university (as differentiated from a medical school) were interested only in replicating themselves and their disciplines through their graduate students and were scornful of any attempt to apply what they taught to real-life situations.

Another innovation relating to the human side of medicine was the emphasis given to family practice. With medical schools in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh stressing specialization, Dean Harrell believed that a tremendous need for primary care in Pennsylvania's rural areas and small towns was being overlooked. Hershey would meet this need by giving its new Department of Family and Community Medicine academic status equal to that of the specialty departments, thus encouraging more students to become family practitioners. (Harrell disliked the term "general practitioner" as too often connoting physicians who tried to practice all phases of medicine, often beyond their competence, and were reluctant to refer patients to specialists.) Other schools had hospital residency programs in family medicine, the dean later explained, "but they were under the control of pediatricians and internists. There were none as an academic department, where the professor of family medicine could talk to the professor of surgery and say, 'You're wrong. This is not the way to do things,' and make it stick."

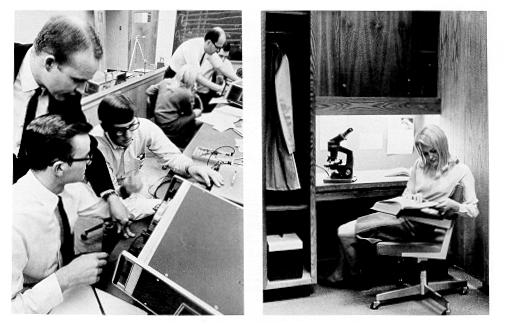

(Left) Physiology students and faculty review oscilloscope findings of nerve impulse experiments. (Right) The College of Medicine included a steadily increasing number of women—from 3 in a class of 40 students in 1967 to 115 in a class of 384 in 1983-84.

In establishing the first full-fledged department of family and community medicine at any of the nation's medical schools, Harrell invited more than a few snickers from other medical educators. Specialization had been the rule for at least thirty years. Because there was no faculty from which to recruit at other institutions, he had to draw upon family practitioners in the Hershey area for his teaching staff. Teaching duties initially reduced the amount of time these physicians could devote to their own practices and understandably led to complaints from local residents. (The hospital eventually did add a family practice center, however.) But the revival of the tradition of the family doctor demonstrated a firm commitment to Primary care that came to be much appreciated by Pennsylvania's citizens. Ultimately almost all other schools followed Hershey's lead by making primary care and community medicine part of every physician's training.

The third innovative department in the College of Medicine was behavioral science. Physicians acknowledged that many medical problems were behaviorally related, yet few medical schools made a clear distinction between aberrant behavior and mental illness, which was the domain of psychiatry. Harrell took the view that since true mental illness was not present in most medical problems that had behavioral overtones, behavioral science should be divorced from psychiatry. At Hershey, behavioral science was considered a basic science on the same plane as physiology or biochemistry, to be used by all clinical fields.

In most other respects, the Hershey Medical Center was like any modern medical school. There was plenty of opportunity for students to specialize. Eight clinical departments and thirteen divisions were operational by 1970-71. The incoming class that year numbered 64 students (not including graduate students in anatomy, physiology, biological chemistry, and laboratory animal medicine), which was expected to be the norm until facilities were expanded. Medical students got one of the best bargains in education to be found anywhere: they were charged only $130 per term in tuition, a smaller sum than undergraduates at University Park or the Commonwealth Campuses paid.

The achievements of the Hershey Medical Center to 1970 represented only a beginning. As in the case of the entire University, further expansion and greater accomplishments were anticipated in the decade ahead.