Penn State began preparing for the transition from war to peace in March 1944, when President Hetzel appointed a Committee on Postwar Problems, comprised of department heads, representatives from extension and research units, and other selected faculty and administrators. Chaired by Assistant to the President in Charge of Resident Instruction A. O. Morse, the committee met as frequently as once a week to discuss proposed veterans' admissions policies, building programs, student support services, and other subjects expected to be of critical importance in the near future. College and university officials throughout the country were bracing for a tidal wave of admissions applications from returning servicemen. Some of these applicants would be resuming an education interrupted by war; others would be veterans who would not have considered furthering their education had not the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944 (popularly known as the GI Bill of Rights) offered financial assistance. No one could predict with certainty how many students would take advantage of the GI Bill, but since it was unprecedentedly liberal in its benefits, the number was sure to be large.

PREPARING TO MEET POST-WAR NEEDS

To be fair to undergraduates already enrolled and insure a gradual transition to peacetime routine, the College decided not to return to the traditional academic calendar until the fall of 1946. In the spring of 1946, after having received an avalanche of requests for admission, it announced that it would give preference to those former Penn State students who had left before graduating to enter military service. This decision evoked much criticism, but President Hetzel believed it to be the only honorable course of action. "We promised them the opportunity to return to college, and we must keep faith," he declared. Second on the priority list were all other veterans. College officials pledged to reserve 75 percent of vacancies for these two classifications, with the remaining 25 percent being set aside for recent high-school graduates.

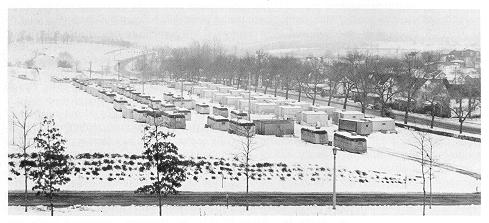

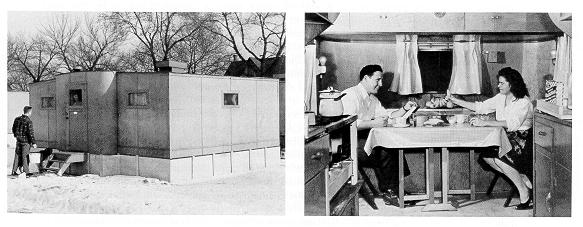

The primary constraint on the number of students who could be admitted was the lack of residential facilities. Penn State and other institutions expanding to meet the needs of returning servicemen hoped to alleviate this problem by erecting temporary dormitories. To aid them, the federal government through a provision in the Servicemen's Readjustment Act made available a large number of surplus buildings that it had acquired for emergency purposes during the war. The College sent representatives to scour the Middle Atlantic states in search of any structure that had been labeled surplus and could be disassembled for transport. Emissaries from other schools were doing the same thing, and competition was intense. The best Penn State could do was to obtain about a hundred trailers that the government had used to house defense industry workers in the New Castle (Pennsylvania) area. Moved to the campus at government expense late in 1945, the trailers were set up on the grassy hillside above East College Avenue and east of Shortlidge Road. The College paid for utility connections, put in dirt streets, made some cosmetic improvements, and rented the trailers for $25 a month to married veterans. Additional units were secured so that by the spring of 1946, 250 trailers were in place at "Windcrest," as the inhabitants dubbed their community.

For unmarried veterans, whose numbers far exceeded their married counterparts, the College purchased fourteen single-story, prefabricated structures capable of housing a total of 850 students. Located on high ground north of Windcrest and just off Pollock Road Extension, the units comprised the residential area of Pollock Circle. All of the approximately 1,200 rooms in the permanent dormitories were allotted exclusively to women, continuing a policy begun during the war. Males granted admission but not accepted for residence in temporary campus housing therefore had to make do with what they could find in town, or commute to school if they lived nearby.

Foreseeing that many more qualified students would apply for admission than town and campus housing could accommodate, representatives from Penn State in February 1946 met with officials from the Department of Public Instruction, the state teachers' colleges, and several private colleges to discuss the possibility of having the smaller schools assume responsibility for the instruction of Penn State freshmen, much in the manner of the College's own undergraduate centers. As institutions devoted exclusively to the preparation of teachers, the state-owned colleges were not expected to be inundated with students and might be able to accommodate additional freshmen. The arrangement would work to the financial benefit of the teachers' colleges. Although Penn State would admit the students, they would pay all tuition and other fees directly to the cooperating institutions. There would be few problems with curricular requirements, since freshmen-year subjects were similar at all schools. At least a few of the teachers' colleges also had the desire to expand beyond teacher training to various liberal arts fields and hoped that the acceptance of Penn State freshmen might prove valuable in convincing officials in the Department of Public Instruction of the wisdom of such expansion.

By mid-1946, with the blessing and encouragement of that department, thirteen state colleges along with Gannon College of Erie and York and Keystone Junior colleges agreed to cooperate with Penn State. (Another private institution, St. Francis College of Loretto, later joined this group.) Under that arrangement, no freshmen (men or women) were to be admitted to the main campus in 1946-47. Instead, they would be sent to the state teachers' colleges, the private colleges, or the undergraduate centers (including the Mont Alto forestry school). All resources at the main campus could then be brought to bear on completing the education of upperclassmen as rapidly as possible. Every student successfully finishing his or her first year at another campus would be guaranteed admission to the main campus as a sophomore.

Penn State admitted more than 2,800 freshmen in the fall of 1946, which together with approximately 7,000 students at the main campus and some 400 sophomores at the undergraduate centers gave the College a record enrollment of 10,200, 55 percent of whom were veterans. That over a thousand qualified students still had to be turned away for lack of space did not result from a lack of effort to find room for them. To make space for even a few more men, the fourth floor of Old Main was converted into a makeshift dormitory. At California State Teachers' College, freshmen slept on cots in the school's gymnasium.

To help those prospective students who were academically able but who were denied entrance because of space limitations, the College, through its Central Extension service, created a special category of "Emergency Credit Class Centers." These centers were to be set up in any community where forty or more students registered and adequate classroom and library facilities existed. Teachers were secured from local high schools, and classes were held in the late afternoon and evening for the duration of a normal sixteen-week semester. While instruction at these emergency centers was supposed to be comparable to that afforded at the various Penn State campuses, College officials forewarned students that there could be no guarantee that institutions other than Penn State would accept credits earned. Nor could there be any assurance that students from the emergency centers would be admitted to the main campus to begin their sophomore year. They would be accommodated only after provision was made for students from the undergraduate centers and the teachers' and other cooperating colleges.

Besides satisfying an educational demand, these emergency credit class centers served a political purpose. The Hetzel administration wished to head off any public outcry that might arise from the College's inability to admit large numbers of academically qualified students, particularly veterans. It was also aware that the directive prohibiting freshmen from attending the main campus had incensed many Centre County residents, who did not like the prospect of students being forced to leave home for a year, often at considerable expense, to attend an institution in their backyard. Despite numerous protests, Hetzel refused to modify the policy, arguing that the land-grant college belonged to all Pennsylvanians, who deserved to be treated equally, regardless of where they lived. It was no coincidence that the resentment among the local populace faded after emergency centers opened in State College, Bellefonte, and Philipsburg—all in Centre County—and in Lewistown, less than an hour's drive from the College. Seven emergency centers eventually were begun (the others were in Sayre, Shamokin, and Somerset) and enrolled about 900 students until their discontinuance in 1949.

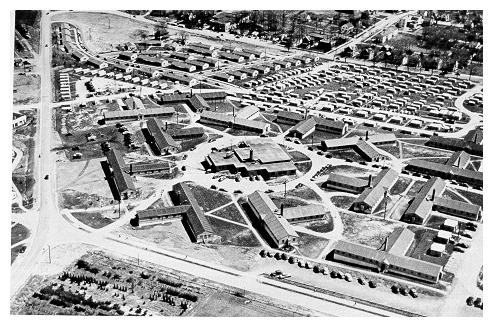

Temporary housing: Pollock Circle (with the PUB in the center), Windcrest (upper right), and Eastview Terrace (upper left).

The full-time student population at all Penn State campuses surpassed the 11,000 mark in 1947-48. To make room for incoming sophomores, the College acquired more trailers for Windcrest (bringing the total there to over 350) and purchased 25 more prefabricated housing units similar to those in Pollock Circle. Known as Nittany Dormitories, the units were set up east of Pollock Circle and south of the poultry barns-not an ideal location, inasmuch as the dorms were usually downwind of the barns. (The situation could have been worse. The University of Maine converted poultry barns themselves to student dormitories.) Additional classroom space was acquired for 1946-47 when the College received a few wood frame government surplus buildings and reassembled them as classrooms between White Building and Grange Dormitory.

Experts in higher education everywhere agreed that once the ex-GIs had earned their degrees, that portion of America's youth seeking a college education would still be significantly higher than in the prewar era. Consequently, in addition to meeting the needs of a temporary influx of veterans, Penn State had to take more permanent measures to prepare its physical plant for the demands of a larger student body in the 1950s. The policy followed in the postwar years did not differ substantially from that of the previous two decades. In January 1944, the board of trustees reaffirmed that, the urgency of the times notwithstanding, the College should undertake expansion in such a way that would not jeopardize its fiscal stability. The institution would borrow large sums of money only to finance construction of buildings-principally residence halls-that generated sufficient revenues over time to pay for themselves. For new classroom buildings, laboratories, and library facilities, the College would look to the Commonwealth for assistance.

The board did deviate from past practice in one important respect when it voted to implement the recommendations made in a report by its student welfare committee. The committee's report pointed out that Penn State "has never been able to admit the proportion of women accepted by other land-grant colleges, and as a public institution it has lost support because of the many disappointed parents who are also taxpayers of Pennsylvania." The committee concluded that the College not only must provide more dormitory space for women, but also "must accept the responsibility of housing more of its men. The situation was urgent before the war, and it will become critical with the larger number of men entering after demobilization."

In June 1944, the trustees authorized plans to be drawn for two new residence hall complexes, one to house a thousand women, the other a thousand men. The women's dormitories were given priority, and groundbreaking occurred early in 1947. Located along Shortlidge Road a short distance from Windcrest, the buildings matched the colonial Georgian style of Atherton Hall and Grange Memorial Dormitory. Simmons Hall, named for Lucretia Van Tuyl Simmons, long-time German department head and confidante of women students, was ready for occupancy in September 1948. McElwain Hall, honoring Lady Principal Harriet McElwain, was opened a year later.

In the spring of 1949, construction began on three residence halls for men, adjoining the three that had been built in the 1920s. The $6 million project also included a dining hall to serve the 1,500 students expected to live in the entire dormitory complex. Now that the College had committed itself to housing more students, it had to offer food service on a scale never before contemplated. A new foods building was built west of Atherton Street near the golf course. This facility reduced operating costs by permitting centralized receiving and storage of all incoming food. The building had its own bakery and butcher shop to further process food before distributing it to the dining halls.

Nearly all building construction suffered from numerous delays and higher than anticipated costs. A nationwide boom in private construction and public works, deferred for years by the war, created a demand for building materials and skilled workmen that could not be met immediately and drove prices steadily upward. In 1945 the General Assembly allocated $7 million for the construction and rehabilitation of buildings at state institutions of higher education and hospitals. About half that sum was targeted for Penn State. The General State Authority had ceased to exist in 1943, the legislature having used budget surpluses to retire its bonds. Because of a scarcity of construction materials, work did not get under way on the College buildings until 1948. By that time, severe inflation had beset the nation. The consumer price index had climbed 34 percent since the end of the war. The 1945 appropriation was sufficient only for the construction of a new classroom building (Willard) and buildings for plant industries (Tyson) and mineral sciences. In its budget request for 1947-49, the Hetzel administration asked for enough money to complete the program as planned. The General Assembly granted $10 million for general operations and $6 million for new construction. Governor James Duff, while genuinely sympathetic to Penn State's needs, regarded the appropriation as one of many instances where the legislature was attempting to spend beyond Pennsylvania's means and pared the amount for construction to $750,000.

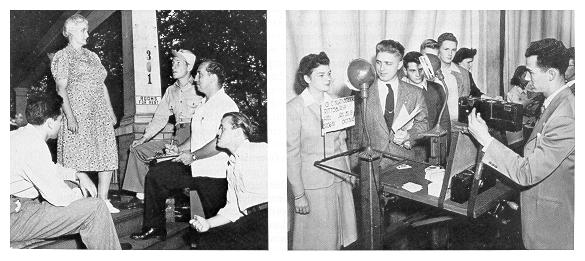

(left) Members of the X-GI Club interview a State College landlady as part of their survey of the availability of off-campus housing. (right) By 1945, as part of the registration process, each student had to have an official identification picture taken.

Duff, a Republican, also used his veto power to reduce the College's general appropriation to $8.5 million. Despite these cuts in Penn State's allotment and similar reductions in legislative appropriations of all types, the governor still incurred the wrath of fiscal conservatives in his party for what they labeled his free-spending policies. And in truth, Duff spent more on education at all levels than had any of his predecessors, even after allowing for inflation. After he had wielded his veto ax, Penn State still received 40 percent more money than it had in the previous biennium.

On another financial front, the College faced the prospect of paying higher faculty salaries. It had to compete with other institutions in recruiting more faculty to keep pace with growing enrollments and keep salaries of current faculty members abreast of the rising cost of living. An assistant professor was then likely to earn about $3,500 annually, and a full professor typically received about $6,000. (A School and Society survey in June 1947 reported average salaries for these two positions at sixty land-grant schools and state universities to be $3,350 and $6,600, respectively.)

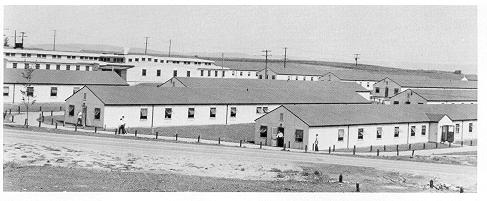

Nittany Dormitories, looking every bit like the surplus barracks they were.

Another handicap to recruitment was the shortage of housing in State College for new members of the professional staff. Some instructors hired in the year or two after the war had to live in Bellefonte, Lewistown, Tyrone, or other outlying towns. The only new housing construction for two years after the war was a group of 80 units (40 double houses) built along South Atherton Street near the fringe of the developed section of the community. These units were sold immediately but did not begin to satisfy a housing demand that was growing more critical with each semester. As a stopgap measure, the College resorted to supplying faculty housing itself, using the same kind of prefabricated, semipermanent designs that it had offered students. In the summer of 1947, it built 76 family units, each arranged in two- or four-unit dwellings located in the extreme eastern corner of the campus above College Avenue and beyond Windcrest. The facilities (Eastview Terrace) were intended to be converted to residences for married graduate students after the emergency had passed.

To help resolve the faculty housing problem, President Hetzel convened a special meeting of town and campus leaders in February 1947. From their discussions came the Borough-College Coordinating Committee, consisting of five borough representatives and three from the campus, to explore all aspects of the situation. The committee found that the main obstacle to more and better housing was a lack of money to underwrite new construction. In March the panel proposed that a public corporation be formed to finance the building of most or all of the three hundred or so single-family dwellings that it estimated the borough needed. Within a month, the corporation became a reality and had netted $50,000 through a subscription drive among local residents. Contracts were signed for the construction of thirty-eight homes in the southwestern section of the borough, with plans for more as soon as additional funds could be raised and private builders secured.

Ralph Hetzel did not have an opportunity to see if the goals of the corporation would be realized. He died of a sudden massive cerebral hemorrhage on October 3, 1947. The 64-year-old president had been forced to curtail many of his administrative activities since July, when he had injured his back and had to undergo surgery for the removal of a spinal disc. He was making such a rapid recovery that his death (attributed to phlebitis, a condition apparently unrelated to his back problems) came as a shock even to his family and closest friends.

Hetzel had served for nearly twenty-one years at Penn State, longer than any president except George Atherton. He presided over two multimillion dollar building programs, saw enrollment mushroom from less than 4,000 to more than 12,000, and helped develop a research program having expenditures of more than $3.2 million annually by 1947. He also launched, albeit reluctantly, a system of branch campuses that were attended by over 2,200 students at the time of his death. Ralph Hetzel was the last of Penn State's presidents whom faculty felt they knew on an almost personal basis, and his passing was received as a personal tragedy by much of the College community. He was also well known and respected among his professional peers. He led Penn State into membership in the National Association of State Universities and served as president of that body in 1934. In 1947 he took office as president of the Association of Land-Grant Colleges and Universities, on whose executive committee he had served for two terms. His unpretentious, steady leadership had helped Penn State weather two crises-the Great Depression and World War II- and would be missed in the equally critical post-war period.

(Left) Simmons and McElwain halls under construction; (right) the ceremony to lay the cornerstone featured (from left) Julia Gregg Brill '21, longtime English literature professor and leader in alumni affairs; Pearl Weston; James Milholland; and Helen Atherton Govier, daughter of President George Atherton.

Named to succeed Hetzel on an interim basis was James Milholland, president of the board of trustees since the retirement of J. Franklin Shields in 1946. A 1911 graduate of the College in history and political science, Milholland had been an alumni representative on the board for twenty-seven years. He was a partner in the Pittsburgh law firm of Alter, Wright, and Barron and had served as judge in Allegheny County's Orphans' Court. Pending the selection of a new president, Milholland gave up much of his law practice in order to devote more time to the affairs of his alma mater.

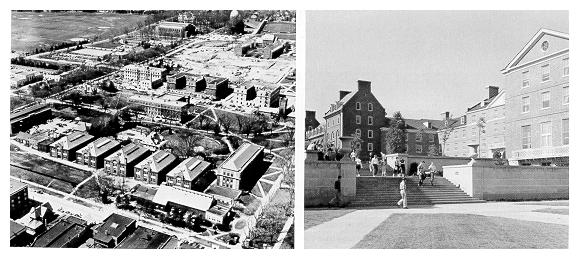

(Left) West Halls, Willard Building, and Mineral Sciences are among the buildings under construction in this 1949 view of the west campus; (right) completed in 1950, West Halls could accommodate 1,500 students.

The Milholland interregnum eventually spanned two and one-half years, during which time Penn State continued its efforts to cope with the temporary crush of ex-GIs while building for the permanent demands of the future. The institution was still forced to send the entire freshman class of 1948, a record-breaking 3,500 students, to the undergraduate centers and state teachers' colleges. That same year the trustees approved an increase in room and board rates. The charge for board, or meals, went from $187 to $200 per semester, while room charges rose an average of $10 and varied between $60 and $110 per semester, depending upon the type of accommodation. Students who resided in the dormitories and took their meals in campus dining halls could be expected to pay a minimum of $900 a year for their education and related expenses, such as clothing and entertainment. Tuition for out-of-state undergraduates was raised from $75 to $110 in an action that was mostly symbolic, since few non-Pennsylvanians were in attendance. Tuition-still termed an incidental fee-for residents of the Commonwealth remained at $50 per semester. However, a "general course fee" of $20, the first fee supplement since 1923, had been introduced in 1947-48. The following year it was consolidated with existing charges for athletics, health service, library use, and damage deposits into a "general fixed fee" of $60 per semester.

The trustees believed that they had no choice but to ask students to pay more for their education. The continuing high rate of inflation threatened the financial soundness of the College unless steps were taken to boost revenues. Early in 1949, Acting President Milholland presented to the legislature a request for $13 million for general maintenance for the upcoming biennium. The General Assembly passed Governor Duff's recommended appropriation of $10.5 million. However, Duff had also convinced the legislature to revive the General State Authority and assured Milholland and other Penn State supporters that the College could expect a generous allocation for the expansion of its physical plant to compensate for any inadequacies in the General Assembly's appropriation. In April 1950, the GSA approved $8.9 million worth of projects, mainly in the form of additions: a fourth floor for the Main Engineering Building and wings for the Mechanical Engineering Laboratory, Recreation Hall, the Library, the Education Building (Burrowes) and Pond and Buckhout laboratories. New chemistry and agriculture laboratories were to be constructed as well.

NEW RESEARCH AND INSTRUCTIONAL UNITS

Expansion, temporary or permanent, took many forms in the post-war years. Besides tremendous growth in the size of the student body and the College's physical plant, sponsored research and the variety of curricular offerings also increased.

World War II had amply demonstrated the value of scientific research to national survival. It had also led to the development of a new relationship between the federal government and the nation's institutions of higher education, as the government called on these institutions not only for manpower training (as it has in World War I) but for assistance in scientific research. Defense agencies relied on the expertise of the academic community to help compress decades of scientific research and development into years or even a few months, so that the results would be of use to the war effort. With the advent of a "cold war" between the United States and the Soviet Union after the Axis powers had been defeated, it seemed to be in the national interest to continue to utilize the technical resources of colleges and universities to maintain a strong national defense.

The government's desire to enlist the aid of these institutions for defense purposes brought about the largest single addition ever to Penn State's research program. For much of the war, Harvard University had operated an Underwater Sound Laboratory in cooperation with the federal government's Office of Scientific Research and Development and the Department of the Navy. Activities at the laboratory dealt with various technological facets of war under the seas, particularly submarine and anti-submarine warfare. Harvard notified its collaborators of its intention to sever all connections with the Underwater Sound Laboratory at the war's end, so the OSRD and the Navy began searching for a new site for the facility. Eventually the decision was made to shift the work formerly done at Harvard to several locations, one of which was Penn State.

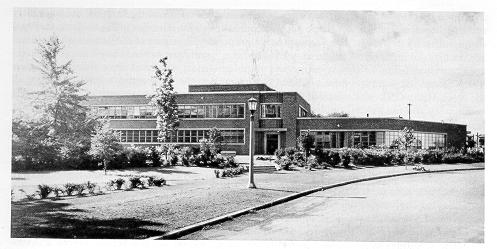

Ordnance Research Laboratory, 1946

The College was selected in an almost casual way. Dr. Eric A. Walker, a Harvard-trained engineer and scientist who had been a guiding force in the USL torpedo research project, had already accepted an invitation to come to Penn State as soon as the war was over to head the Department of Electrical Engineering. Late in 1944, recalled Walker, "the Navy approached me and asked if I would put together a small group of people to continue the work on torpedoes [at Penn State.] The definition of small was never made precise. I had in mind and the captain I was discussing it with in the [Navy's] Bureau of Ordnance had in mind about eight people and $120,000 per year. This was not a big deal, and we never took it to President Hetzel." Walker simply asked Harry Hammond, Dean of Penn State's School of Engineering, if he would approve the addition of a modest program of torpedo research in the school. Hammond readily consented. Walker's proposal meshed perfectly with his own plans to promote more engineering research.

No sooner had Hammond given his consent than key officials in the Navy and the OSRD decided that torpedo research deserved greater support and asked Walker to set up a laboratory at Penn State containing at least 100,000 square feet and employing over one hundred persons. A proposal of that magnitude had to be put before Hetzel and the trustees. On a snowy day in January 1945, Walker and several high-ranking naval officers called on the president at his private residence. They outlined a program whereby the Navy would pay for the construction of a large laboratory building on the campus, where defense research would be done under contract to the Bureau of Ordnance. The Bureau would pay all operating and maintenance costs plus annual fees to the College. Hetzel expressed his willingness to have his institution cooperate with the Navy in what seemed a financially worthwhile as well as patriotic endeavor. Yet the whole matter had arisen so suddenly that he could not help asking his visitors, why Penn State? "Well, Walker's here," replied one of the officers, "and it's a nice place." That simple remark apparently satisfied the president. He promised to recommend approval of the Navy's proposition when he took it before the board of trustees at its semiannual meeting a few days hence.

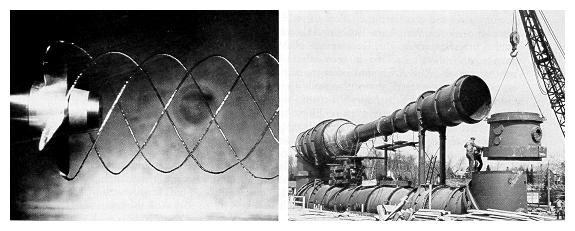

(Left) Researchers at the ORL devoted much of their attention to solving the problem of cavitation—shown here by the helical pattern of air bubbles trailing a torpedo propeller—which creates noise that can be detected by sonar; (right) Garfield Thomas Water Tunnel main section under construction.

The board likewise agreed to the establishment of a defense laboratory, and construction began on the Ordnance Research Laboratory, as the facility was designated, as soon as weather permitted. Located along Atherton Street in the southwest corner of the campus, the laboratory and a field-testing station on Black Moshannon Lake (about 20 miles north of State College) cost a half-million dollars. For administrative purposes it was part of the School of Engineering, and its director, Eric Walker, also fulfilled his commitment to head the electrical engineering department. The ORL's scientists and engineers-most of whom came from the Underwater Sound Laboratory-were accorded faculty rank in the engineering school. Virtually all the work at the ORL was classified top secret for security reasons, so the rest of the Penn State community and the general public had only vague notions as to what kind of investigations the Navy sponsored there. Most outsiders knew only that the Bureau of Ordnance had placed a high priority on torpedo research and development, and that many scientists and engineers at the laboratory were engaged in improving homing torpedoes and perfecting devices that prevented these weapons from circling the launching vessel and destroying it by mistake.

There was also a need to test torpedo shapes, their propeller designs, and the hull designs of submersible ordnance in general. To do that kind of work, the Ordnance Research Laboratory needed more sophisticated equipment. In 1948 construction began on a circulating water tunnel. Named for Lieutenant W. Garfield Thomas '38, one of the College's first alumni to give his life in World War II, it was the largest tunnel of its kind in the world. Objects to be studied for their hydrodynamic qualities were placed in a section of the tunnel where a 2,000-horsepower motor drove water at velocities up to 60 feet per second.

Speaking at the dedication of the Garfield Thomas Water Tunnel on October 7, 1949, Assistant Secretary of the Navy John T. Koehler tried to explain why the Navy so eagerly sought partnerships with Penn State and other institutions of higher education. "The last war proved conclusively that it is not possible to conduct basic research during hostilities and to convert knowledge gained thereby into weapons soon enough to have a decisive effect," he stated. "Investment of military dollars in scientific research in peacetime pays dividends in the form of time saved in wartime, and saving time during a war means saving lives, material, and money." Most of America's colleges and universities accepted this premise. Patriotism and the lessons of the recent global conflict were too deeply etched in most people's minds for voices to be raised against academia's participation in military research.

By 1949-50, annual research expenditures of the Ordnance Research Laboratory (including the water tunnel) reached $1.4 million. The Navy did not limit its patronage to the ORL, however. At the Engineering Experiment station, it continued to subsidize investigations, begun during the war, into the failure of welds on Liberty ships. It also continued its wartime contract with the Petroleum Refining Laboratory to develop special lubricants and hydraulic fluids. Investigators in the Department of Metallurgy in the School of Mineral Industries received the Navy's backing in their efforts to improve the ductility of steel plates used in combat vessels. The Army and (after its creation as a separate service in 1947) the Air Force supported a few research projects as well. The most noteworthy of these was the study of the ionosphere initiated by the Army's Watson Laboratories and later sponsored by the Air Force in cooperation with the Department of Electrical Engineering. Researchers attempted to determine what effects changes in the ionosphere or the upper layers of the earth's atmosphere had on high- and low-frequency radio transmissions.

By 1950, the federal government was spending $50 million a year on non-agricultural research at institutions of higher education, with much of that sum underwriting defense-related work at land-grant schools. While educational administrators welcomed such support, they expressed the view that Washington should also allocate public funds for research that did not have any direct bearing on military strength but would be equally vital to America's general well-being and would push back the frontiers of knowledge. Expectations that such assistance might be forthcoming were heightened in 1949 when Congress created the National Science Foundation. Both scientific and engineering research, it was hoped, would benefit from NSF support in the coming decade.

While research was growing in importance as a mission of the College, undergraduate instruction remained its primary responsibility. During the 1940s Penn State increased the number of baccalaureate degree curriculums it offered from 47 to 57. The School of Engineering had regained some of the popularity that it had lost during the depression but still ranked second to Liberal Arts in student body size. In 1949-50, the College's eight schools and their undergraduate enrollments were: Liberal Arts, 2,637; Engineering, 1,817; Agriculture, 1,481; Education, 1,262; Chemistry and Physics, 731; Home Economics, 635; Physical Education, 448; and Mineral Industries, 445.

Home Economics, the newest of the College's schools, was created in 1949 in response to the increasing diversity of fields of study found under the administrative umbrella of the discipline and the rising demand for graduates of those fields. When Penn State launched its home economics curriculum in 1907, it did so with the intention of preparing teachers for secondary schools. Yet from the beginning, home economics graduates entered many areas other than teaching: food science, nutrition, and textiles, to name just a few. By the eve of World War II, home economics at many colleges and universities also included the study of social interrelationships in family and community life. At Penn State, however, the Department of Home Economics was still devoting most of its resources to turning out teachers-at least that was the contention of Grace Henderson, newly appointed (1946) head of the department. A graduate of the University of Chicago and Ohio State University, Henderson had taught at several other universities and had worked as a home economics specialist for the governments of West Virginia and New York. Her experience convinced her that fundamental changes had to be made in the administration and curriculums of home economics if the College were to meet the challenges of modern society.

Henderson wanted the Department of Home Economics to be removed from the School of Education, with its emphasis on teacher training, and made into a new school with departments of its own. She pointed out that of the forty-four land-grant institutions awarding degrees in home economics, only Penn State made the curriculum a subordinate department in a school of education or similar administrative unit. The success of the Ellen Richards Institute, which pointed the way toward diversity in home economics, was made even more conspicuous by the fact that the institute had no connection with the School of Education. Creating a new school of home economics would strengthen fields other than teaching by making them more visible to prospective faculty and students and to potential sponsors of research.

Demand for home economics graduates came not only from public schools but from government agencies, private research laboratories, and industry; as a result, demand exceeded the supply. The problem was made worse, Henderson observed in a report to Acting President Milholland, by the high turnover in the various home economics fields. Women constituted three-fourths of the graduates in the College's Department of Home Economics, and half of them worked in their chosen profession less than two years before leaving to become full-time wives and mothers. The obvious solution in Henderson's estimation was to attract more students to the profession, and a new school of home economics would help to do that. It would also lift Pennsylvania from the lowest quartile among the 48 states in the number of home economics graduates per unit of population. Milholland and the board of trustees found Henderson's arguments persuasive and approved creation of the school effective January 1, 1949. It was to have six departments: Home Economics Education, Child Development and Family Relationships, Clothing and Textiles, Foods and Nutrition, Home Management, and Hotel Administration.

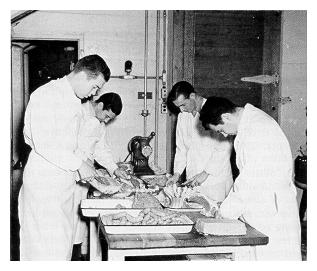

Hotel administration students learn meat-cutting techniques; the meat will later be sold to the public at the College meat shop.

Of the six, the most distinctive was hotel administration. By the mid-1930s, a sizable number of Penn State alumni from a variety of curriculums had obtained professional employment in hotel and restaurant management. They regularly pressed President Hetzel to have their alma mater establish a degree curriculum in their field; the only schools in the East having similar programs were Cornell and Michigan State. Hetzel spoke favorably of this concept-it was certainly not at odds with the alms of the Morrill Act-and even began referring to Pennsylvania's "hospitality industry," an obvious analogy to the other industrial fields in which the College trained personnel. All of these actions occurred at the very time the Commonwealth first allocated funds to publicize its recreational and historic attractions to potential tourists from neighboring states. The president finally committed himself to beginning a course study in hotel administration after it received the endorsement of the Pennsylvania Hotels Association. Inaugurated as a baccalaureate course of study within the Department of Home Economics in 1937-38, the curriculum was among the most diverse in the College. Professionals in the hotel and restaurant field had to have broad preparation in many fields-food science, nutrition, chemistry, accounting, labor relations, even some engineering. Many faculty members in other departments, especially in liberal arts, held the opinion that the new curriculum was inappropriate at the collegiate level and should be taught in a vocational school. But it enjoyed the personal support of President Hetzel, and its popularity with students, especially after the war, left no doubt that it deserved departmental status in the new School of Home Economics.

The initiative of alumni was an important factor in getting hotel administration accepted as a department, but alumni did not always get what they wanted in curricular matters. Not long after the end of the war, renewed agitation began for detaching the commerce and finance curriculum from the School of Liberal Arts and making it into a new school of business. Commerce and finance still enrolled a larger number of students than any other curriculum in Liberal Arts. At their January 1947 meeting, the College's trustees received a petition from J. K. Lasser '20, Alfred M. Paxon '27, and Raymond C. Kramer '22-all prominent in national business circles-setting forth the disadvantages of maintaining a narrow commerce and finance curriculum under Liberal Arts and urging that it be made the core of a business school. "It is extraordinary," the petition read in part, "that the principal state-supported institution of higher education in the second most important industrialized state in the United States should rank almost at the bottom of the list of state colleges in providing training to the men and women who must be the future executives of industry." Ben Euwema, who succeeded the retired Charles Stoddart as dean of the School of Liberal Arts in 1946, argued against the petition and took exception to its allegations that commerce and finance was too narrow and had remained stagnant for the past twenty years. Euwema did not speak for all the liberal arts faculty, however; in the commerce and finance department itself and in the Department of Economics, the teaching staff overwhelmingly favored the creation of a school of business.

The trustees' committee on educational matters, to which the full board had referred the petition, took note of the strong feeling on both sides but recommended that the question of a business school be studied further, and the board agreed. Cost was one inhibiting factor. At a time when Penn State's resources were being spread thin, a school of business would require a substantial outlay of funds for classroom and office space and for more faculty. The board of trustees and the administration also had before them proposals for separate schools of home economics, forestry, and journalism. The College could not possibly afford all of these new schools, even assuming each was justifiable on academic grounds. Consequently the merits of each proposal had to be weighed with extreme care. In the end, only the need for a School of Home Economics was judged compelling enough to warrant favorable action.

UNDERGRADUATE CENTERS MADE PERMANENT

Growth on the main campus was paralleled by the expansion occurring at the undergraduate centers. Recognizing the important responsibilities that would fall to the undergraduate centers in the immediate postwar years, the trustees in January 1945 reaffirmed their earlier policy on branch campuses. The College would consider any reasonable request from communities desiring an undergraduate center, so long as the community proved the need for it and agreed to furnish and maintain offices and classrooms. The centers were to be financially self-sustaining, just as they had been in the 1930s (and as all non-agricultural extension work was). The trustees saw no point in asking the Commonwealth for money for branch campuses when appropriations for the main campus were so inadequate. Their insistence on self-support meant that often student fees at the centers were higher than those charged at the main campus.

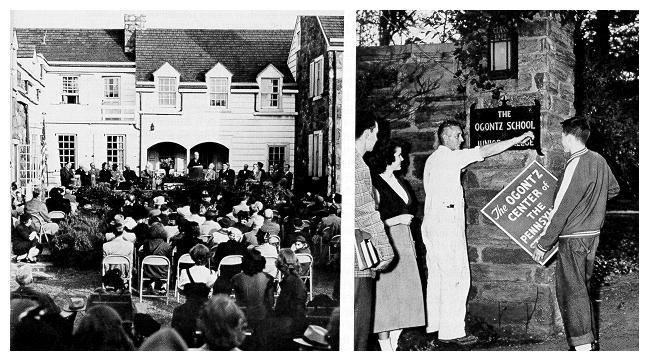

(Left) dedication of the Behrend Undergraduate Center, October 1947, at which James Milholland is speaking; (right) Ogontz changes hands, September 1950.

In the absence of any official declaration by the Hetzel administration, the four undergraduate centers (Altoona, DuBois, Hazleton, and Pottsville) became de facto permanent appendages of Penn State. They were no longer considered temporary measures to overcome the fiscal adversity of the Great Depression or to cope with the onslaught of thousands of ex-GIs in the late 1940s. Instead, although the specific locations of centers were subject to change, it was a generally accepted fact that Penn State would have branch campuses for freshmen and sophomores long after the veterans had graduated.

Permanency made no change in the administration of the centers, all four of which together with Mont Alto came under the supervision of the Central Extension Office, still headed by J. O. Keller. Official pronouncements declared that teachers at the centers were, as they had been since the 1930s, members of the regular College faculty and entitled to all the privileges thereof. There were differences, however, and they were not exactly subtle. Academic titles clearly denoted that one taught at an undergraduate center: Assistant Professor of Engineering Extension, for example, or Extension Instructor in English. Salaries were lower for branch campus faculty also, in some cases as much as 20 percent less than what a teacher of comparable rank and responsibility earned at the main campus. Enrollment at the four undergraduate centers in 1946-47 was 1,709, 80 percent of whom were veterans. Altoona had the largest student body (598) and DuBois the smallest (337).

In 1947 the College added another site for undergraduate instruction when it leased facilities of the defunct Mary Lyon School for Girls from the school's new owner, Swarthmore College. Adjacent to the Swarthmore campus, the Lyon School was converted for use by freshman day students and students in the School of Engineering's technical institute program. Penn State officials termed the site the "Swarthmore Class Center" to distinguish it from the four undergraduate centers. The distinction reflected some uncertainty about the Swarthmore center's future. Assertions were made that the creation of the center represented a first step by the College to gain a permanent foothold in the Philadelphia area, to the eventual detriment of the city's other colleges and universities. Swarthmore indeed seemed to be a departure from Penn State's previous pledge to offer undergraduate instruction only where other institutions could not readily serve the needs of the community. Nor was there a groundswell among local citizens in favor of the center. However, from the time it first opened its doors, the Swarthmore Center enrolled more degree students than any of the other branch campuses.

Penn State was also eager to lease space at Swarthmore because of the decision of the Central Extension Office to switch several of the technical institutes from part-time evening instruction to full-time day instruction. The College sponsored twelve permanent technical institutes scattered across Pennsylvania that enrolled a total of 6,000 students annually. It had the largest engineering extension education program in the nation, but it still could not meet the demand for engineering technicians. By allowing students to complete in nine months a curriculum that formerly required five years, the need for technicians could be more effectively satisfied. The technical institute in Chester was not suitable for daytime classes, but the Swarthmore facilities were ideal. The technical institute at Wilkes-Barre also began a full-time day program in 1947.

Erie and Harrisburg Joined Swarthmore as class centers in 1948. Penn State had maintained a technical institute in Erie since the 1920s. It was always well attended, serving employees in the electrical, transportation, pulp and paper, and related industries that formed the heart of Erie's economy. After the war, a group of civic leaders led by attorney J. Elmer Reed asked the Hetzel administration to establish a full-fledged undergraduate center in their community. Before the College could accede to the request, backers of the proposed center had to provide the appropriate quarters. Reed and others then appealed to the Erie school board for the use of several vacant buildings but were turned down. This rebuff soon proved to be a boon, for it aroused public interest and ultimately several offers for sites were tendered. The one accepted was from Mrs. Mary P. Behrend, widow of Ernst R. Behrend, a founder of the Hammermill Paper Company (one of Erie's largest employers) and a generous contributor to local philanthropic projects. To honor the memory of her husband, Mrs. Behrend donated the family's Glennhill Farm estate, a 400-acre tract near suburban Wesleyville. The College spent $50,000 to modify a dozen buildings on the estate for use as classrooms, laboratories, a library, a cafeteria, and faculty apartments. About a hundred freshmen were in the first class when the Erie Class Center opened in September 1948. The technical institute was also moved to the center and rescheduled for daytime work.

The facilities at the Harrisburg center were less elaborate, consisting of a main administration building on Front Street converted from an old gray stone mansion and classroom space in various other buildings nearby. It, too, had a daytime technical institute. All facilities were leased by the College, and after the needs of veterans had been met, the center was closed in 1951.

A third center of sorts also opened in 1948, this one in Bradford. It was unique in that it was in essence a branch campus of a branch campus, since it was staffed by faculty from the DuBois undergraduate center. The Bradford center lasted only a year. Nonetheless, the Central Extension Office thought enough of the Bradford campus to award it the special classification of "Credit Class Center"—a term not to be confused with the seven "Emergency Credit Class Centers" already mentioned that were in operation at the same time. (The Central Extension staff never explained why there was an emergency in towns like Bellefonte, Lewistown, and Philipsburg but not in Bradford.)

More conventional efforts were made by the undergraduate centers in Altoona, Pottsville, and Hazleton to meet the postwar flood of students. A large enrollment at the Altoona center's quarters in the downtown YMCA and adjacent buildings had caused overcrowding even in prewar times. Seeing that Penn State had no intention of closing its branch campuses after the war, the Altoona center's local advisory board, headed by businessman J. E. Holtzinger, in 1946 raised $40,000 to purchase the old Ivyside amusement park in the northwest section of the city. Closed since the early 1940s, the park contained more than a dozen buildings on a tract of 53 acres. A shortage of materials and labor prevented any immediate renovations, so classes were still held downtown. By the end of 1947-48, conditions there reached the intolerable. In a desperate attempt to open a new campus, a "do it yourself" campaign began. Using paint, lumber, tools and cleaning supplies donated by Altoona area businesses, volunteer work parties of students, faculty, and interested residents swarmed over the park in August 1948. Much work remained to be done by professional crews, but the amateurs had accomplished enough to open Ivyside in time for 488 freshmen and sophomores to begin the new school year there.

The Hazleton and Pottsville centers also got new and permanent homes, again owing to the initiative of their local advisory boards. The Pottsville center, located in a former public-school building in that community, in the fall of 1948 moved some of its classrooms and all its administrative offices to a newly purchased and remodeled twelve-room residential building on Mahantongo Street. In 1949 Hazleton became the third Penn State branch campus (after DuBois and Erie) to acquire an estate with a spacious mansion and plenty of room for future expansion. The new site, on a hilltop three miles from downtown Hazleton, was Highacres, originally the 66-acre estate of the late Alvin Markle, Sr. It owner, Luzerne County bus company executive Eckley V. Markle, donated a portion of the property, and the Hazleton Center's advisory board purchased the remainder. Classes began at the new location in September 1949. That year 2,016 full-time freshmen and sophomores were in attendance at the seven branch campuses, the distribution being: Swarthmore, 447; Altoona, 405; Pottsville, 319; Hazleton, 296; DuBois, 241; Harrisburg, 172; and Erie, 136. Approximately 11,130 students attended the main campus, and another 1,300 freshmen were assigned to the state teachers' colleges.

Still another permanent site for an undergraduate center came via donation early in 1950 when Abby A. Sutherland, president and owner of the Ogontz School and Ogontz Junior College, presented these properties to Penn State. Located a short distance north of Philadelphia in the Rydal Hills section of Abington Township, Ogontz had been founded in 1850 in Philadelphia as the Chestnut Street Female Seminary. In 1883 it moved to Ogontz, the country estate of financier Jay Cooke, from which it derived its new name. Its distinction as a finishing school for girls caused the institution to need larger quarters, and in 1917 it moved again, this time to the Rydal site, a few miles from the Cooke property. A Junior college was added in 1930. Sutherland, who had become principal at Ogontz in 1909 and its owner four years later, was nearing her retirement as the school approached its centennial but was unable to find a successor with whom she was completely satisfied. After a court decision held that Ogontz was subject to taxation despite its claim as a nonprofit endeavor, Sutherland decided to close both schools and give the property to Penn State for use as an undergraduate center.

Only a few changes and improvements were required to ready the campus, which consisted of eleven buildings on 43 acres, for incoming classes in September 1950. Having been a boarding school, the new Ogontz Center was able to provide dormitory space for two hundred women. Since there was no need for the College to maintain two centers in the Philadelphia area, undergraduate instruction at the leased Swarthmore facilities came to an end in 1951, and the technical institute was moved to Ogontz.

A UNIQUE STUDENT BODY

In the fall of 1947, at the crest of the flood of returning military veterans, Penn State had a greater proportion of ex-GIs among its full-time students (80 percent of 7,700) than any other institution of higher education in the Commonwealth. But housing on and off campus was more readily available in urban areas, and both Pitt and Penn enrolled more veterans, as did many other schools in other states. Having ranked among the nation's twenty largest undergraduate institutions just prior to the war, Penn State slipped to thirty-ninth place in 1947-48. Of the 2.2 million Americans attending college that year, 1.15 million were former members of the armed services.

Windcrest, looking east.

Ex-GIs gave a distinctive flavor to the College's student body. At least 500 of those taking classes on the main campus were married and had brought their families to State College. Most of them lived in Windcrest. It was the non-academic side of college life that residents of that little community would remember best-the beds that folded from the living room walls of those tiny trailers, the kitchens equipped with gasoline or kerosene stoves, the communal baths (the trailers had no sewer connections), the camaraderie that evolved among residents who shared these "luxuries." Through the GI Bill, the government paid the cost of books and tuition and gave married veterans a monthly stipend of about $120. In an era of rising prices, that amount did not go far beyond the necessities of food and rent. Students often had to rely on parental help, bank savings, and working wives to make ends meet. Still, these students and their non-married fellows in Pollock Circle, Nittany Dorms, and elsewhere had survived greater hardships while in uniform. A few more years of sacrifice did not seem too high a price to pay for a college education.

These ex-GIs were in a hurry, determined to make up for lost time and get on with their careers as soon as possible. Most of them had specific goals in life and were willing to work hard to achieve them. Their maturity and experiences left a lasting imprint on many teachers. Students who had served in the military "gave a different leaven to the undergraduate student body," remembered Kent Forster, who had taught history to hundreds of former servicemen. "They raised questions in class [and] had pretty critical comments to make based on their own exposure to life overseas and in the armed forces that were very stimulating and made for exciting instruction.... One simply dared not go before a class of those people without having something to say. They wanted no part of an instructor who tried to get by without adequate preparation."

(left) These units were war-surplus additions to the original group of Windcrest trailers. (right) Every inch of the interiors of the Windcrest trailers was put to good use.

The veterans also made an impression on recent high-school graduates. "College was not what I expected, coming right out of high school," recalled a young man who entered Penn State as a freshman in 1946. "Instead of horsing around with a fun-seeking teenage gang as I did in high school, I found myself living in a married students' place and going to classes with bomber pilots, infantry platoon leaders, and veterans of Omaha Beach. It wasn't what I thought college would be like." On some college campuses, upperclassmen too young to have served in the war tried to subject those bomber pilots and platoon leaders to the humbling rites of freshman hazing, only to be told in very explicit terms what they could do with their dinks and white socks and freshman handbooks. Upperclassmen foolish enough to persist after this kind of rebuff risked physical assault. Such unpleasantness was largely avoided at Penn State, however. All first-year students were assigned to undergraduate centers or other campuses, and the few sophomores at the centers had the good sense to treat ex-GIs with due respect.

The fact that students who had spent time in the military seemed to be willing to shoulder a few more inconveniences on their way to getting their degrees did not mean that they meekly accepted the status quo at Penn State. In fact, their previous experiences with "Uncle Sam" made them more prone than their predecessors to voice dissatisfaction with conditions they found at the College and in town.

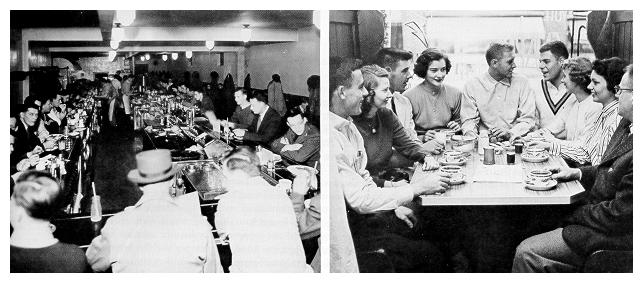

Student gripes ran the gamut from the trivial to the fundamental. Many of the problems students singled out for criticism resulted from overcrowded conditions. "The main prerequisite for entrance to this college seems to be the ability to stand in line for hours," grumbled one weary undergraduate. Students queued up from day one: at registration, in the dining halls, while buying books, at athletic events, even visiting the infirmary.

Another frequent target of student criticism was the steadily rising cost of getting a college education. After facing two consecutive years of increases in both fees and room and board charges, students in the spring of 1949 tried to dissuade the board of trustees from enacting yet another increase. "Penn State used to be known as the place where a student could get a good education without the bankroll needed to attend an Ivy League college," said the Daily Collegian in a May 21st editorial. "Nowadays though, Penn State has almost slipped out of reach of the middle income group. The paper claimed that the average nonveteran who lived in a dormitory and ate in a College dining hall paid $250 more in 1948-49 than in the previous year. Combined with other expenses, the cost of a year at Penn State had surpassed $1,000.

(Left) Veterans crowd Fred's Restaurant on South Allen Street, 1946; (right) a Corner Room booth.

Students were also unhappy with the administration's opposition to a proposal for a student-operated cooperative bookstore that would sell books, supplies, cigarettes and candy, and other small articles at reduced prices. In the fall of 1947 the All-College Cabinet allocated $2,000 to finance the start of operations. Before the cooperative store could become a reality, however, it had to receive approval from the board of trustees. On December 5, 1947, the trustees' executive committee rejected the concept of a nonprofit bookstore on the campus. "Because of the public character of this institution," the committee explained in a written statement, "it is not in order for building space, light, heat, and maintenance services to be used for a project which will compete with private enterprise."

The student body did not waver in its support of the cooperative idea. Of 4,000 students polled on the question by the All-College Cabinet, 93 percent favored it. Student government leaders accused the executive committee of being more interested in placating town merchants than in helping lower the cost of getting an education.

The intensity of reaction to the committee's decision made the trustees reconsider the matter. At their meeting in June 1948, they consented to a student-run store that could sell only used books and a limited line of stationery items. A board of six students and four faculty was to oversee the operations of the store, which was set up in one of the government surplus buildings that was being used as a student activities center. The new cooperative bookstore in reality did little more than make permanent the used book exchange that undergraduates had been running informally for the past year.

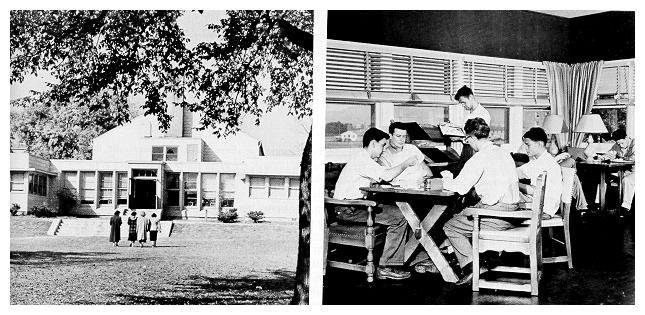

Students had only slightly better luck in reaching another of their chief objectives, one that had no bearing on the cost of education but did make the educational experience a little more tolerable. Before the war, a portion of Old Main had been reserved for student offices, meeting places, a lounge, and a snack bar. The postwar expansion of the College's administrative staff displaced most student space in the building except for the food service, and even that was discontinued for a time. Students complained long and loudly over the absence of any facility they could call their own. The trustees formed a special committee to explore the possibility of constructing a student union building, but the $4 million cost of such a structure was deemed prohibitive. No state money was available for the building, and having the College borrow funds on its own to finance construction would contradict its policy of obtaining loans solely for self-amortizing buildings.

As an interim solution, the College secured a war surplus structure that had originally seen duty as a USO center in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, and turned it into the Temporary Union Building, or TUB. Reassembled along Shortlidge Road behind the Infirmary, the TUB contained a ballroom large enough to accommodate 250 couples, offices for student organizations, the used book exchange, and a snack bar. From the day it opened in October 1947, the TUB was too small to meet all of the demands students placed on it, so it was supplemented with a scaled-down version made from one of the dining halls in the Pollock Circle dormitory complex. Only unmarried veterans lived in Pollock Circle, and the residence hall area was off limits to women. That was also the rule for the PUB, or Pollock Union Building, a feature that seriously compromised its value in the eyes of many students.

Predictably, students' relations with town residents did not improve during the postwar years. Many ex-GIs tended to be hard drinkers-not necessarily alcoholics, but certainly more steady imbibers than State College residents had known in earlier times. Excesses associated with beer and hard liquor convinced many townspeople that the borough, headed toward a moral abyss in the 1930s, had finally taken the plunge.

Some students, whether drinkers or teetotalers, had little more affection for many borough residents. A general resentment prevailed against what one undergraduate described as "the smug, go-to-hell attitude and the obvious bandit-like tendencies of many of the townspeople, who would die a parasite's death without the College." Especially bitter complaints were directed against landlords who, reacting to inflationary pressures, continually raised rates. Some relief had been afforded in 1946, when the federal Office of Price Administration still supervised rent and other housing costs. In response to numerous complaints from faculty and students, the OPA in September 1946 ordered State College landlords to roll back rental rates to levels in effect on January 1 of that year. The federal government soon thereafter withdrew from attempts to control prices, and rents began to climb once more. Not only housing costs went up. "Less hash for more cash" became a common jeer among students who took their meals in State College eateries.

Another sore point between town and gown concerned the movies shown in the three local theatres. Students considered the 550 admission charge outrageously high, especially since the theatres allegedly showed mostly "B" pictures, supplemented with an occasional high-quality film on its second or third run. Students must have found movie going worthwhile nevertheless, for in 1947 they mounted a campaign to repeal the borough's ordinance against Sunday shows. A proposal to permit theatres to remain open on Sundays was put on the November general election ballot. The discussion preceding the vote resembled the controversy surrounding the legalization of alcoholic beverage sales within the borough in the 1930s. Students saw the question as a recreational issue. Many townspeople regarded it as a moral problem. A former State College burgess told students the ban on Sunday movies was for their own good. If it were lifted, he cautioned, the community would inevitably fall prey to "honky-tonks, gambling dens, and immoral sewers ready to skim you out of your last penny." A majority of the voters who cast a ballot on the referendum apparently agreed, and the proposal was defeated 282 to 252.

Relations between the College and the local population were also disrupted by the racial discrimination practiced by town barbers. Blacks had attended Penn State as early as 1899, when Calvin H. Waller of Macon, Georgia, enrolled in the preparatory course (he graduated with a degree in agriculture in 1905). But blacks did not arrive in significant numbers-if twenty or thirty can be considered significant-until after World War II. The adamant refusal of barbers to accept them as customers aroused the indignation of a large segment of the student body, particularly ex-GIs, since nearly all the black students were veterans. In the spring of 1947, several student veterans' organizations and the All-College Cabinet launched a coordinated effort to find a solution to the problem.

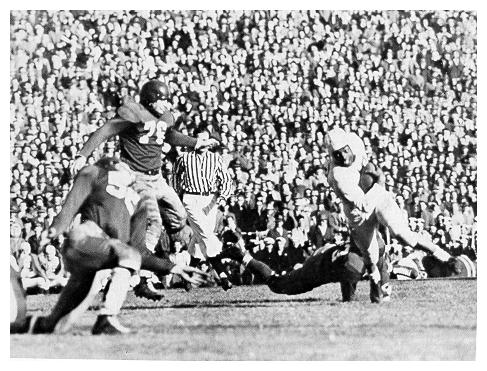

Lines between campus and borough were not drawn nearly as sharply on the racial issue as on other points. Many town residents found discrimination as reprehensible as the student leaders did. The College had no grounds for official action since the matter was not an academic one and did not occur on campus. Penn State authorities left no doubt where their institution stood on the question of racial equality, however. They refused to have the College participate in several intercollegiate athletic contests, including a football game with the University of Miami, because Penn State's black athletes were not permitted to participate. The College also accepted an invitation to the 1948 Cotton Bowl in Dallas only after guarantees were forthcoming that the Nittany Lions' black players would be allowed to participate. Penn State became the first school in Cotton Bowl history to field a team that included blacks.

Acting as private citizens, a number of faculty Joined town residents in forming the State College Council on Racial Equality in 1947. The council in turn Joined with student groups in attempting to take legal action against the barbers. This approach came to nothing after the discovery was made that Pennsylvania law, which forbade racial discrimination in public places, did not include barbershops in that category. After further protests (including picketing by a newly formed chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) the council raised enough money to lease space in a downtown building and bring in a barber from outside the area.

An issue did not have to possess profound moral or financial implications to capture students' attention. Probably nothing aroused such widespread indignation or galvanized so large a portion of the student body into action as the lowering of women's hemlines. Skirt and dress lengths went from just above the knee during the war to just below the knee by 1947 and gave every sign of plummeting further. Penn State men joined their counterparts on campuses all over the nation in a desperate appeal to coeds to think for themselves and not blindly follow the dictates of a few fashion moguls in New York or Paris. Rallying to the cry of "Stem the hem!" the All-College Cabinet in November 1947 proclaimed "Short Skirt Week," highlighted by a Friday night dance in Recreation Hall. Women were advised in advance to wear skirts or dresses that were knee length or shorter. While dancers swayed to the melodies of Huff Hall and his orchestra, judges armed with tape measures roamed the floor to make sure that all hemlines met the required length. The evening was capped by the selection of a coed queen who best exemplified the "old look." These efforts were futile, however, and longer dresses and skirts dominated the campus fashion scene for the next decade and a half.

The Temporary Union Building (left), reassembled after its move from Lebanon, Pa., gave students a place of their own to relax and enjoy social activities (right).

Men had no monopoly on being vocal in airing their grievances. Women, too, could be vociferous in their protests, as evidenced in an episode involving Pearl O. Weston '29, the new dean of women. Weston had succeeded to the deanship upon the retirement of Charlotte Ray in 1946, having served as her assistant since 1942. The new dean also found fault in the changes in women's fashions, but it was not the lowering hemline that bothered her. Rather, she was distressed over the increasingly casual attire in which coeds appeared at meal times. In April 1948, Weston issued a directive stating that coeds were not to enter the dining halls wearing "raincoats, jeans, shirts hanging out, kerchiefs on the head, bedroom slippers, pajamas, bathrobes, nightclothes, shorts, or halter-style dresses." Loose-fitting slacks were permitted at breakfast and lunch only. Monitors would be stationed at dining hall entrances, the dean warned, to see that these regulations were enforced.

The Women's Student Government Association Senate met in emergency session and criticized Dean Weston for her "dictatorial" methods. When the dean asked Mortar Board, the senior womens' honorary, to serve as monitors, she found not one student interested. A search among Windcrest wives and adult women in town proved equally fruitless. Finally Weston used the student employment office to secure five undergraduate women to do the job for $1.50 per day. Before the monitors had an opportunity to enforce the new regulations, the WSGA and Dean Weston reached a compromise. The dean promised to rescind her directive, in return for which the WSGA pledged to put more pressure on its constituents to dress in a more satisfactory manner.

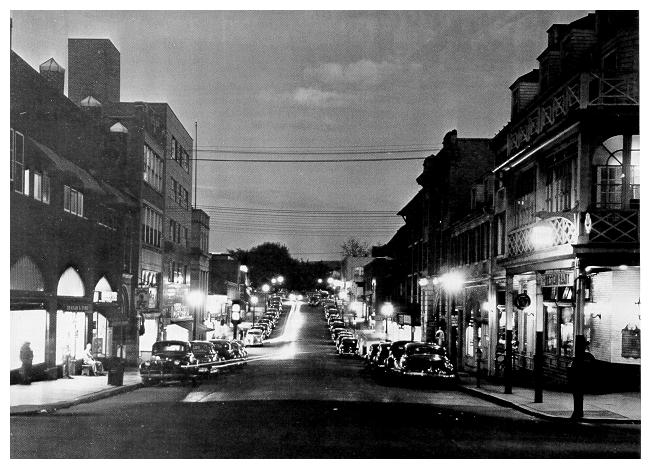

South Allen Street by night, as seen from the main campus gate.

A similar outcome climaxed an equally tense situation early in the following academic year. The Interfraternity Council in 1947 had adopted a code of conduct that prohibited female guests in fraternity houses from going beyond the first floor (or into the rooms of individual fraternity brothers if they were located on the first floor). The code also banned the consumption of alcohol by members of either sex regardless of age any time women were present in the house. The IFC was either unable or unwilling to enforce this code. As the new school year got under way in September 1948, Dean Weston felt compelled to act. She announced that no sophomore women would be permitted to enter fraternity houses at any time, for whatever reason, and that if fraternities did not adhere at once to their previously agreed upon code of conduct, she would extend her edict to include junior and senior women as well.

Dean Weston intended her ruling to strike a serious social blow against fraternities. It was her belief that as the youngest women on the campus, sophomores tended to be more naive and eager to win the favor of the Greek societies. When the Interfraternity Council appealed to Dean Warnock to intercede, he could only second Weston's decision. "I can't see that the fraternities have anybody but themselves to blame for this action," he wrote in a Collegian article on October 3. Four weeks after the ban on sophomore visitation had been invoked, Deans Weston and Warnock consented to its repeal, hoping they had taught fraternities a lesson. The Greeks were to make an honest effort to comply with the 1947 code of conduct, and representatives of the deans' offices were to make periodic inspections to see that they did.

Neither men nor women campaigned strenuously for the establishment of off-campus houses for sororities. There had been some talk of the idea among students in 1946-47 as a means of alleviating the campus housing shortage, but a concerted drive to move sororities into town never occurred. The administration was firmly opposed to such a move, and there was little likelihood of finding suitable quarters in the borough at a time when housing of all kinds was III short supply. In 1949, the last of the sororities left the campus cottages they had been occupying for nearly two decades and moved into specially designed suites in the new McElwain and Simmons dormitories.

Enough ex-GIs had left Penn State after the June 1949 commencement to allow the admission of freshman women to the main campus in September for the first time in four years. Indeed, veterans so swelled the ranks of those receiving diplomas that Beaver Field could not accommodate all graduates along with their families and friends. Two ceremonies had to be staged, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. Three months later, the green bows in the hair of first-year women and the name cards around their necks indicated that at last the campus was getting back to normal. Perhaps no group was happier to see a return to normality than the coeds themselves. "When we first came to campus," remarked a senior in December 1949, "every good-looking fellow we met in our classes was married. Things are different now!"

THE PENN STATE IMAGE

The five years after World War II constituted the waning phase of Penn State's provincial or cow college era. The Pennsylvania State College shared with other land-grant schools the reputation for having an intellectual climate that was inferior to that found at many private colleges and universities. This reputation stemmed partly from a widespread popular misunderstanding of the alms of the Morrill Act, legislation that was frequently equated with government support for agricultural education and research only. The College's location in the pastoral surroundings of rural Centre County magnified its image as a "hick" school. The institution also had the misfortune to begin life as The Farmers' High School, an ill-chosen appellation that somehow embedded itself in the minds of many people who knew little or nothing else about Penn State's history.

The College was a farm school only during its first two decades, and even then, the majority of its graduates engaged in nonagricultural pursuits. If the school could be identified with one type of education, it was engineering, at least for the half-century beginning with George Atherton's presidency and ending with the Great Depression. Yet when Pennsylvanians thought of an engineering school, it was the privately endowed Lehigh University that was likely to come to mind for many of them. For liberal stimulation of the intellect, the University of Pennsylvania was widely regarded as the Commonwealth's foremost institution, with the University of Pittsburgh and perhaps Temple University ranking higher than Penn State in that category. The College also suffered because, as an Eastern institution, it could easily be contrasted with Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, and other schools that formed the Eastern establishment. Critics merely had to cite the puny holdings of Penn State's library to dismiss its claims to being anything more than a vocational institution, even when compared to some of the land-grant universities of the Midwest.

Most students were as familiar with the 100 block of South Allen Street as they were with the campus itself.

The cow college image would not have persisted for so long had it not been adopted, perhaps unconsciously, by a large portion of the College's own faculty and students. Too many members of the Penn State community considered their school worthy of competing on the gridiron or the gymnasium floor with the likes of Penn or Syracuse or Ohio State but inferior to those institutions by almost every academic standard. Many Penn State teachers and alumni preferred to think of their college as just that: a college-a small school set in splendid isolation, where close friendships and happy memories abounded, unspoiled by intrusions from the outside world. That attitude was not consistent with Penn State's standing as the largest self-styled "college" in the country. Nor did it encourage any but the most modest assertions made on behalf of the institution's academic accomplishments.

Wallace Triplett breaks through the SMU defense—and the color barrier—at the 1948 Cotton Bowl.

Penn State's self-image began to change in the late 1940s. Many faculty and administrators who had served for decades retired or died within a few years of the war's end, including no fewer than five deans. Dean of the School of Agriculture Stevenson W. Fletcher, a member of the horticulture faculty since 1916, retired in 1945, as did Liberal Arts Dean Charles Stoddart. Dean of Women Charlotte Ray and Dean of Men Arthur Warnock stepped down on account of age in 1946 and 1949, respectively. Frank Whitmore, for eighteen years Dean of the School of Chemistry and Physics, died in 1947. Retirements took their toll among long-time department heads, as well: Charles Kinsloe of electrical engineering, Charles F. Noll of agronomy, Asa Martin of history, Jacob Tanger of political science, David McFarland of metallurgy, Laura Drummond of home economics, John Henry Frizzell of public speaking, and William S. Dye, Jr., of English, to cite an incomplete list. Other retirements of note included those of Dr. Joseph Ritenour, since 1917 director of the campus health center; E. B. Forbes, successor to

Henry Armsby as director of the Institute of Animal Nutrition; and Willard Lewis, head librarian for eighteen years.

The biggest single change, of course, centered on the passing of Ralph Hetzel, for though President Hetzel had given Penn State years of devoted service and had seen the College through difficult times, he had never seemed interested in having Penn State assume a place of greater visibility among America's institutions of higher education. Acting President James Milholland was interested, but his administration was a brief one and he had more urgent problems to confront. Building plans and state appropriations were two of these problems. Two more involved dealing with growing faculty discontent and finding a permanent successor to Hetzel.