In spite of the limitations it faced, The Pennsylvania State College experienced steady growth during the early 1920s, thanks to an increasing number of high school graduates who elected to continue their formal education. Penn State's undergraduate population grew from about 2,900 to 3,500 between 1919-20 and 1925-26. The College continued to attract large numbers of students from all parts of the Commonwealth and in a typical year enrolled about 8 percent of all full-time undergraduates at Pennsylvania's institutions of higher learning. Centre and Allegheny counties regularly provided more students than any other counties, although Philadelphia, Montgomery, Schuylkill, Luzerne, Lackawanna, and Dauphin counties each usually contributed over a hundred students annually. Residents of states other than Pennsylvania comprised about 5 percent of the total student body.

By the mid-1920s, nearly all freshmen held diplomas from accredited high schools, reflecting the great strides Pennsylvania was making in improving its secondary education system. For those applicants who had not graduated from accredited high schools (usually students from rural areas), Penn State still administered a special entrance examination at the campus before the start of every academic year. Because the number of students who applied for admission far exceeded the number the College was able to accept, it no longer permitted the entry of freshmen with "conditions," that is, lacking some high-school credits that were prerequisites for certain courses of study. In earlier years admission to the School of Liberal Arts might be granted, for example, to a student who lacked the required units of foreign language study, on the condition that this deficiency be erased during the first year. Penn State undergraduates still came from essentially the same backgrounds as their predecessors from the pre-war era. William Hoffman, who succeeded Howry Espenshade as registrar, found in 1925 that over one-third of the students listed their father's occupation as farmer, storekeeper, superintendent or manager, railroad employee, or salesman. In one significant change from the previous survey, the category of "laborer" had grown to become the sixth most common occupation.

More students were interested in engineering than in any of the other curriculums, and the School of Engineering remained the largest of the College's six undergraduate schools throughout the 1920s, enrolling over 1,100 students annually and offering baccalaureate programs in architecture, architectural engineering, civil engineering, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, electrochemical engineering, industrial engineering, milling engineering, and railway mechanical engineering. Taking into account students enrolled in the School of Mines and Metallurgy and in the chemical engineering (formerly industrial chemistry) curriculum of the School of Chemistry and Physics, nearly half of Penn State's undergraduates were pursuing engineering degrees. The School of Mines and Metallurgy offered baccalaureate curriculums in ceramic engineering, metallurgical engineering, mining engineering, and mining geology. Traditionally the smallest of the College's schools and constantly plagued by financial and leadership crises, Mines and Metallurgy was nonetheless the largest of its kind at any institution east of the Mississippi River.

The most notable changes in student curricular preference involved agriculture and liberal arts. Following its reorganization by Dean Hunt, agriculture had ranked behind only engineering as the most popular field for undergraduate study. By the mid 1920s, however, the School of Agriculture had fallen on hard times and had dropped to third in size among the College's schools. Careers in agriculture had lost some of their appeal, as American farmers coped with the worst depression in market prices since the Civil War. Many agriculturists blamed their hardships in part on Penn State and other land-grant institutions, charging that experts from these schools had caused them to become too efficient and to produce more than the market could consume. There was some truth in these complaints, although the inevitable slump in overseas demand after the war and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's traditional emphasis on increased production were also important causes of the depression.

While the School of Agriculture struggled to readjust itself to new conditions, Liberal Arts expanded and became the College's second-largest school. The growth of the liberal arts at land-grant institutions was a common phenomenon of the 1920s, and Penn State, with about one-third of its undergraduates seeking liberal arts degrees, approximated the average of its counterparts in other states. This growth did not necessarily mean that students were becoming more interested in humanistic or intellectual studies. Most of the increased enrollment in the School of Liberal Arts came in the commerce and finance curriculum, which by 1925-26 accounted for over half of the 718 liberal arts undergraduates. Seeming to have taken their cue from President Calvin Coolidge's axiom that "the business of America is business," students enrolled in commerce and finance in droves, making it even more popular than electrical engineering, which since the turn of the century had been the College's largest baccalaureate program. Commerce and finance majors typically studied such subjects as business law, marketing and merchandising, principles of economics, corporate finance, and accounting. The growth of the School of Liberal Arts was therefore a response to the same stimulus that was giving rise to new schools of finance and business administration across the nation. It was not a sudden manifestation of undergraduate inclination toward subjects legitimately termed liberal arts. The school's other two curriculums, arts and letters and pre-legal, experienced only moderate growth.

The College's entire female undergraduate population, October 1926.

The School of Education, too, offered professional training and also enjoyed steady growth. In 1925-26, 456 undergraduates were registered in this school, including 321 women, most of whom were in the home economics program. Having proved its worth during the war, the study of home economics became immensely popular among women on college campuses everywhere. At Penn State, three-fourths of all female undergraduates were enrolled in that curriculum in a typical year. The College could have admitted three times the number of qualified applicants had it possessed more living and laboratory space for its home economics students. Other baccalaureate programs in the School of Education were industrial education and arts and sciences education. The latter was subdivided among 20 or more options according to the subject-history, geography, mathematics, and such-the student wished to teach.

In fulfillment of their degree requirements, many students in the School of Education, particularly those in the home economics and art education curriculums, received a significant amount of instruction in the fine arts. Such subjects as art history, painting and drawing, interior decoration, and costume design had been shifted in 1920 from the School of Liberal Arts to the School of Engineering. There they came under the administrative responsibility of the new Department of Architecture whose faculty also taught the industrial arts and graphics courses required of most engineering students. No degree studies were available in any of the fine arts, including music, which was taught in the School of Education. The curricular organization established in the 1920s was to remain practically unchanged until the 1950s.

The diversity of these curriculums drew many students to Penn State in the 1920s. Equally attractive was the relatively low cost of a Penn State education, a feature that had been a hallmark of the College from its very beginning. The College catalog of 1925 informed prospective undergraduates that they could expect to spend $500 to $800 annually, depending upon how frugally they lived. Men could obtain lodging on the campus or in town for between S90 and $130 a year. Most lived in town, either in rooming houses or at fraternities, since dormitory accommodations were extremely limited.

After the conversion of McAllister Hall to a women's residence in 1915, the only lodging the College offered to male students was the upper floors of Old Main. Watts Hall, having living facilities for about 110 men, was completed in 1923 as the first of a multi-unit residence hall complex located on the west side of the campus; but a year later, safety and sanitary inadequacies forced College authorities to cease using Old Main as a dormitory. Varsity Hall, a companion to Watts and the first structure to be erected using proceeds from the Emergency Building Fund campaign, was opened that same year to supersede the Track House as a residence and training facility for athletes. Regardless of where they lived, all males had to take their meals off campus. Dining privileges could be secured in local boarding houses for $6 to $8 weekly.

Females, who generally comprised about 10 percent of the student body, lived in McAllister Hall, the Women's Building, or several houses on the campus that had at one time been faculty residences. So great was the demand from women for admission that the administration permitted fifty or so to live in town with specially selected families. Coeds took their meals in the McAllister commons or in a small dining area operated by home economics students in the Women's Building.

One solution to the problem of housing for women was to permit them to form sororities and acquire houses just as the men did. Perhaps conscious of the measure of equality women had won for themselves during World War I, Penn State coeds had repeatedly petitioned to form social clubs, ultimately hoping to affiliate these clubs with national sororities. Dean of Women Margaret A. Knight admitted that the lack of living accommodations was the greatest problem facing women at Penn State. However, she rigidly opposed the formation of sororities on the grounds that they were undemocratic, elitist, and steered girls away from the proper ideals of a college education. Over the dean's objection, the girls won a partial success in December 1921 when the College Senate's committee on student welfare approved the formation on a trial basis of the first women's club, the Nita-Nee Campus Club. The Senate committee gave its consent grudgingly, and stipulated that neither Nita-Nee nor any other club subsequently formed could use Greek letters or admit freshmen.

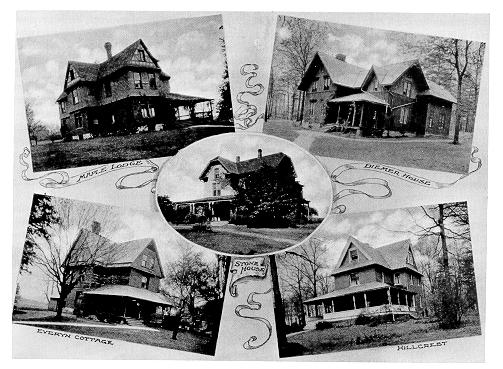

In the 1920s, women were housed in at least five campus "cottages" in addition to the Women's Building and McAllister Hall.

Charlotte E. Ray succeeded Margaret Knight as dean of women two years later. A Pittsburgh high-school teacher and assistant dean of women for Penn State's summer sessions, Ray did not share her predecessor's antipathy toward sororities. In 1925, in her annual report to President Thomas, she observed that Nita-Nee and five other clubs were "doing good service in the promotion of scholarship and improved conduct" among women students. Ray endorsed a petition advanced by the clubs that they be allowed to seek national affiliation, and convinced the Senate to give its approval. The Alfost Club became the College's first national sorority when it was installed as the Nu Gamma Chapter of Chi Omega in September 1926. By 1930, four of Penn State's ten women's clubs had become affiliated with national sororities. In 1928 the College administration, no longer deeming the existence of these groups detrimental to student life and wishing to make more dormitory space available to incoming coeds, assigned five campus "cottages" (actually rather formidable structures that had once served as faculty residences) to the five oldest clubs.

Along with finding a place to live, the greatest concern of most Penn State students, male or female, was a financial one. The College's "incidental fee" by the 1920s was a euphemism for tuition, even if the catalog did state that "no tuition or matriculation fees are charged to Pennsylvania students." Thirty years earlier, when it was $20 or less, this fee may have indeed been incidental, allowing Penn State to claim legitimately that it was tuition-free. A fee of $100-the sum charged after 1923-was the largest single expenditure for students and in essence did constitute tuition.

The most serious financial disadvantage encountered by students attending rural Penn State rather than an urban college or university was the scarcity of part-time jobs. Employment that was available -mostly washing dishes or waiting on tables-did not pay well and was monopolized by juniors and seniors. A variety of scholarships and, loan funds had been set up, often through the generosity of alumni, but these reached only a small fraction of the student body. Regardless of the modest expense of a Penn State education, if a student's family lacked adequate monetary resources or if the student had not obtained well-paying summer employment, the cost of four years of college could still be beyond reach.

Fortunately, the 1920s were not years of financial hardship for most students, as Pennsylvania and the nation settled down to nearly a decade of economic prosperity. This relative affluence spawned what has often been called the "mad, bad, glad" era of campus life, a time of hedonistic revelry among undergraduates, many of whom were careful never to let pursuit of a bachelor's degree interfere with having a good time. It was the golden era of the raccoon-coated, hip-flask-toting "Joe College." Students endeavored to unshackle themselves from what they disdained as the old-fashioned ideas and values of their parents and grandparents. Prohibition, enacted by constitutional amendment in 1920, was a target made to order. Consumption of alcoholic beverages became more popular than ever on college campuses. Drinking was a perfect way to protest "puritan" morality, strike a blow for youthful freedom, and have a good time all at once. Smoking cigarettes and wearing short skirts became common among coeds for much the same reason. Such critics of contemporary mores as H. L. Mencken, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Sinclair Lewis were widely read and admired by the college population.

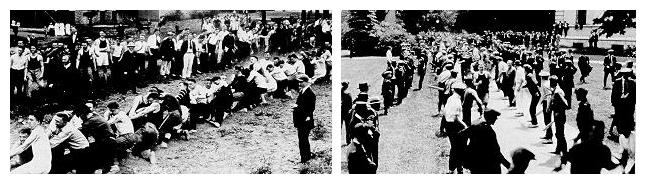

Class conflicts: freshmen run the gauntlet, 1922 (left); tug of war, successor to the more brutal scraps of the early 1900s (right).

Yet Penn State students seemed to have been more comfortable with the status quo than some of their contemporaries on other campuses. Perhaps that was to be expected from a group whose educational interests were so tied to material culture. Granted, rarely did an issue of the biweekly Penn State Collegian appear that did not reverentially invoke the name of the iconoclastic Mencken and his caustic American Mercury; and after reading the novels of Sinclair Lewis, undergraduates might share the author's scorn of the blind orthodoxy and provincialism that allegedly shaped middle-class life. Nonetheless, these students were the sons and daughters of Babbitts and had grown up along Main Street. They exhibited little of the contempt for established values that would be a distinguishing feature of the college scene in the late 1960s. Dean of Men Arthur Ray Warnock could truthfully state in 1923 that "there is evident in our student body almost none of the unrest or rebellion in matters of religion, politics, and social codes that characterize some of the colleges at the present time." Judging from the chronicles of the Collegian, when students did feel the urge to protest, the issues generating the most concern were the gradual decline of class customs, the possible ban against house parties, and enforced attendance at daily chapel.

The dean of men had a direct interest in all these matters. Arthur Holmes had performed many of the duties associated with that position, but not until 1919 did the board of trustees officially create the post. Arthur Warnock, a graduate of the University of Illinois and assistant dean of men there since 1910, was the first to hold the job. A firm believer in student government, Warnock was impressed upon his arrival at Penn State by the degree of self-rule exercised by the undergraduates. Student government had changed little from the time of its creation in the early days of the Sparks administration. An elected Student Council represented the general interests of the student body, while the Student Board acted in an advisory capacity to the College Senate on academic questions. The Student Tribunal enforced the observance of class customs.

The continuance of these customs and the kind of school spirit they encouraged was a topic of much concern throughout the 1920s. Poster night was the last survivor from an era when sophomores considered it their duty to manhandle freshmen as part of the newcomers' initiation into college life. Late one evening in September or October, the freshmen would be routed from their beds by paddle-wielding sophomores and made to parade in their night clothes through the campus and borough streets. Periodically a freshman would be called from the line of march to dig for water in the middle of an unpaved street or bark at the moon or perform some other equally ludicrous feat. Around midnight the marchers assembled at "Co-op Corner" (the corner of Allen Street and College Avenue), where sophomores distributed posters, paste, and brushes to the freshmen. The posters, prepared beforehand by the sophomores, contained a set of rules to be obeyed by the first-year men and were worded in a most insulting manner. The freshmen were then made to apply these posters throughout the community. "All of the downtown buildings and barns for miles around State College were well covered with these learned instructions," remembered one participant, "so that no freshman could possibly have an excuse for not knowing all the customs and rules he was expected to obey." This mass of students was nearly uncontrollable, and poster night always brought with it much destruction of private property. Sophomores often used their paddles, for instance, to persuade small groups of freshmen to raid local orchards, the fruits of these endeavors being carried back to stockpiles in the sophomores' rooms.

Dean Warnock branded poster night "a relic of the cow college days," a bit of juvenile excess long since abandoned by more sophisticated schools. Prodded by the administration, the Student Council replaced poster night in 1922 with stunt night, a frolic designed to take place mainly on the campus and on a more organized and thus more manageable basis. The hapless freshmen were still paraded through town, but the procession terminated at Holmes Field (on what would become the HUB lawn). There, illuminated by arc lights thoughtfully supplied by the Student Council, they were expected to perform various stunts. Some of these activities were relatively tame, while others recalled the humiliation and sometimes savagery of poster night. One stunt required freshmen in groups of forty to strip to their underwear, form a circle, and pile all of their clothes in a heap in the center. At a given signal, the forty students had thirty seconds in which to find and put on their own clothes. Clothing unclaimed at the end of the allotted period was discarded. After observing this stunt, a reporter for the Penn State Collegian noted that "Inasmuch as the majority of the new men have not learned the art of arising at 7:50 on chapel mornings, dressing hastily, and arriving at the auditorium just as the last stroke of eight ceases, quite a few went around during the remainder of the evening in a negligee condition." (It was not recorded whether women were present.)

College officials saw no real improvement in the substitution of stunt night for poster night. At the conclusion of stunt night festivities, sophomores continued their tradition of coating the frosh with molasses and feathers and whacking them black and blue with paddles. Furthermore, vandalism did not significantly decrease, with State College candy stores and movie theaters continuing to be favorite targets for late night student raids. The Student Council subsequently initiated a new series of class scraps. Unlike the pitched battles of the Atherton era, the new tug of war, tie-up, and other scraps were lackluster contests that aroused little enthusiasm among the student body. Sometimes so few sophomores showed up for these events that the scraps had to be canceled. Student leaders warned that the College spirit was being lost, and the Collegian railed at the growing number of "cake eaters" and "lounge lizards" who were fast replacing the "he-men" as the core of the undergraduate population. Some alumni campaigned to have the hard-hitting scraps of their own college days reinstated. But these protests were in vain, as most formal scraps disappeared before the decade was out.

The demise of the scraps and other organized violence against freshmen did not bring an end to customs, however. A fairly strict code of conduct and dress continued to be applied to the first-year men and women. Besides mandating the wearing of the traditional green dinks, customs prohibited male freshmen from occupying the wall along College Avenue at the foot of Old Main, using the front entrances to classroom buildings, smoking, walking on the grass, or dating coeds except on special occasions. The Student Tribunal, convening in solemn judgment as often as twice weekly during the fall semester, delivered swift justice to frosh who ran afoul of these sacred customs. One student, found guilty of wearing red socks rather than the prescribed black, was sentenced to write Student Rule 12-the statute dealing with freshmen dress codes-2,100 times. Another unfortunate, pleading guilty to "associating with the fair sex," first had his head shaved and then was forced to wear a petticoat and a lady's hat to classes for a day.

While such activities may have been no less childish than poster night and stunt night, at least no harm came from them, and perhaps a few students even learned some much needed lessons in humility. Nevertheless, Dean Warnock saw a need for a more serious and systematic introduction to college life and worked with faculty and the Student Council to inaugurate Freshmen Week in September 1925. Beginning a few days before registration, Freshmen Week was intended to acquaint new students with both the academic and social facets of Penn State in a congenial atmosphere free from the intimidation of upperclassmen. Faculty members gave talks on how to study, how to use the library, and the history of the school, while representatives of student organizations provided information on the functions of their groups. Several hours were also set aside for psychological and aptitude tests. Evenings were reserved for social events at which freshmen could get to know one another and develop personal ties that would help them make the transition from home and youth to college and adulthood. Freshmen Week helped personalize life at an institution that by its growth was inexorably becoming more impersonal.

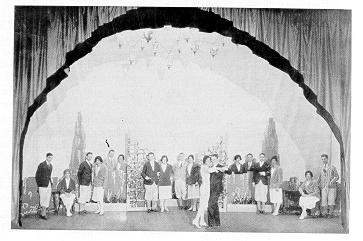

"The Kid Himself" — a Thespian production of 1926 and one of the last to use an all-male cast.

Freshmen Week was a great success and was to be a fixture at Penn State for many years to come. It fared better than an earlier brainchild of Dean Warnock's, the Penn State Student Union. Warnock was concerned that because of a lack of organized extracurricular activities, too many undergraduates, especially those males who did not belong to fraternities, were not sufficiently involved in College life. At Illinois he had been instrumental in founding a student union to act as an umbrella organization in sponsoring everything from student vaudeville shows to intramural athletics. In January 1920, a similar organization, the Penn State Student Union, was established at the College, with Warnock and Coach Hugo Bezdek as two of its chief boosters. A student union building was added to the list of structures the Thomas administration hoped to erect with Emergency Building Fund monies.

But the union idea never caught the enthusiasm of the students, and the organization soon became moribund. Its only legacy was an extensive system of intramural athletics-over 80 percent of the student body participated in union-sponsored programs in baseball, basketball, football, boxing, golf, tennis, wrestling, and track. Perhaps the student union did not last because, contrary to Dean Warnock's view, Penn State students did have sufficient extracurricular outlets in everything but athletics. Student government, honorary societies, YMCA, YWCA, Outing Club, Glee Club, College band, Thespians, and Penn State Players were only a few of the many groups active in non-class activities during the 1920s. Students interested in publications, for example, could choose from at least a half dozen periodicals: Penn State Collegian, Penn State Engineer, Penn State Farmer, Froth, La Vie, and the annual student hand book. And almost every academic department had its own interest group, such as the Sirloin Club (animal husbandry), Crabapple Club (horticulture), and Motive Power Club (railway mechanical engineering).

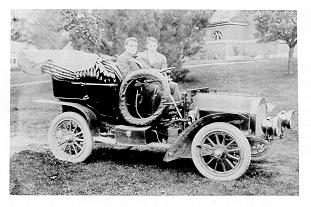

The automobile brought a new dimension to student social life.

The proposed student union also had to contend with a strong countervailing force in the fraternity system. By 1923, forty-seven fraternities, most of which had national affiliations, had been established at Penn State, and their numbers continued to grow as the decade wore on. These fraternities consistently encompassed nearly half of the male undergraduate population and, according to Warnock, accounted for 80-90 percent of the students who held positions of leadership in College affairs. However, certain features of the fraternity system as practiced at Penn State distressed the dean of men and persuaded him that a student union should be founded as an alternative. Warnock was not against fraternities per se; indeed, he was to serve later as educational advisor and chairman of the National Interfraternity Conference and was present at the creation of more Penn State fraternities than any other individual. Warnock merely wanted the fraternities to institute reforms that would guarantee that scholarship and moral rectitude would be encouraged rather than ignored.

In describing Penn State fraternities in a letter to John Thomas in 1923, Dean Warnock noted that "their scholarship is not so good, their chapter management is not so good, and their attitude toward serious things has been characterized too greatly by indifference." Fraternities were becoming havens for students "of the type that has no sustained interest in the better things of college life," Warnock complained, and these students were in turn having a detrimental influence on their more academically inclined fraternity brothers. The dean took special aim at house parties, festive events held periodically during the school year but most prevalent during the Pennsylvania Day weekend in the fall and commencement week in June. Following the custom set before the turn of the century, dates were still "imported" for these occasions. Because few rooms were available to the visitors, the girls resided with their chaperones at one or more temporarily vacated fraternity houses or boardinghouses. Dances and other social mixers that highlighted the house parties were held at various campus and town locations and were also carefully chaperoned, yet enough drunkenness, sexual misconduct, and other breaches of discipline occurred to distress Dean Warnock, the dean of women, and the College Senate. "It cannot be said that house parties are desirable," sniffed Margaret Knight, who placed them in the same category as sororities as far as their contribution to the betterment of college life was concerned. The senate threatened several times to ban house parties unless the Interfraternity Council implemented reforms, and house parties actually were outlawed during commencement week in 1925.

Some problems relating to student life, most visible among fraternity men, applied to many "independents" as well. One such involved the automobile. Automobiles permitted undergraduates to get away from the watchful eyes of College authorities and symbolized the freedom that so many students were seeking. Assuming that a group of students could obtain some alcoholic beverages-a task that by all accounts does not seem to have been made any more difficult by Prohibition-a car provided the means to escape to some secluded location where the beverages could be consumed secure from discovery by College officials. The automobile also played an important if subtle role in the transformation of sexual mores during the 1920s. It afforded male students a mobility that infinitely complicated the responsibility of College authorities to see that relations between sexes remained honorable. Dean Warnock often cited the changing code of conduct between men and women as presenting some of the knottiest problems with which he had to deal. "Too many students are, frankly speaking, girl crazy," he affirmed in his annual report to President Thomas in 1923, adding, as if in wonderment, "I understand this is the case in the outside world as well." In June 1923, the board of trustees finally prohibited all undergraduates from having cars except under special circumstances.

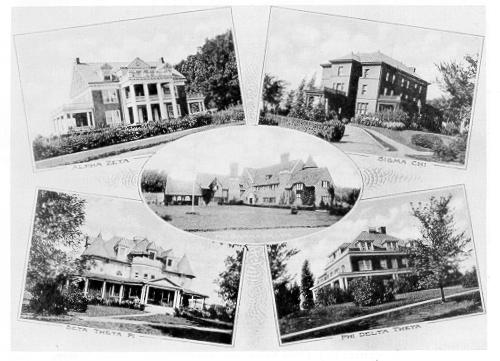

On-campus fraternity houses of the 1920s.

The cries of anguish over the trustees' restriction on automobiles (which was enforced with varying degrees of severity) were mere whimpers compared to the howls of protest over mandatory chapel attendance. Penn State was one of the largest institutions of higher education in the nation to compel students' presence at worship services. College officials enforced the attendance requirement-which since the war was two days per week plus Sunday-by carefully recording absences and giving students passing or failing marks based on the number of absences for each semester. Undergraduates failing two semesters were liable to be dismissed and at a minimum were required to maintain satisfactory chapel attendance during the summer session following their senior year before receiving diplomas. In the spring of 1923, the student body drew up a petition asking the administration and trustees to eliminate the compulsory aspect of chapel. Their request was summarily rejected. Soon after John Thomas left for Rutgers, the student council conducted a referendum on the chapel question. Voluntary attendance won by a five-to-one margin. Once more, a petition was sent to the trustees, who again dismissed it without consideration. Chapel attendance remained a graduation requirement for the rest of the decade.

The Importance of Extension

Only one student in every five who received formal instruction from Penn State during the 1920s was enrolled in an undergraduate or graduate curriculum. Approximately 80 percent of the College's total student body, defined in the broadest sense, knew little and cared less about wearing dinks, pledging sororities and fraternities, or attending house parties. These were the students who were taking instruction through Penn State's extension courses, students who could not or had no desire to acquire a college degree, but who did have a need to further their education.

The Schools of Engineering and Agriculture were among the most active participants in the College's extension program, with engineering reaching by far the greater number of persons in classroom settings. By 1926, evening branch schools existed in Allentown, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Reading, and Williamsport and had a combined enrollment of more than 3,200 students. These schools, each supervised by a full-time director and staffed with a faculty drawn from local industries, offered three-year courses of study leading to certificates in nearly a dozen engineering fields. No two schools offered identical courses since the curriculum was geared to the economy of the community in which the school was located. Because they emphasized practical applications and excluded the kind of theoretical knowledge normally associated with engineering education at the college level, the curriculums of the evening branch schools carried no college credit. Students could earn credit, however, by completing correspondence courses. Correspondence instruction was very popular and by the middle of the decade accounted for more students than the branch schools. In addition, the School of Engineering made available a variety of informal extension courses. Foremost among these were the foreman training programs, twenty to thirty of which were given annually throughout Pennsylvania under the aegis of such companies as the Lehigh Valley Railroad at Sayre and Easton, the Hamilton Watch Company at Lancaster, U.S. Refractories at Mount Union, and the Lorain Steel Corporation of Johnstown. Extension specialists could also tailor instructions to meet the unique requirements of individual firms. Typical was the course in "Public Relations and Industrial Economics" that was created for the Philadelphia Electric and West Penn Power companies.

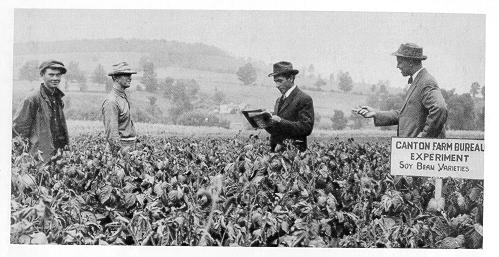

The coal agent and an extension specialist conduct a field demonstration for Bradford County farmers.

All engineering extension activities came under the supervision of the Department of Engineering Extension. Heading that department for nearly a decade was Norman C. Miller, under whose supervision Penn State came to have the fourth largest engineering extension enrollment among American colleges and universities. He left in 1925 to take a similar post at Rutgers University and was replaced by J. Orvis Keller, who had directed the pioneer Army Ordinance course at the College during the war and who since 1922 had headed the Department of Industrial Engineering. Even though its services were constantly in demand, engineering extension received virtually no state or federal funds. Its operations had to be financially self-sustaining. Besides the department head, the full-time faculty consisted only of a field staff of three or four men and the evening school directors.

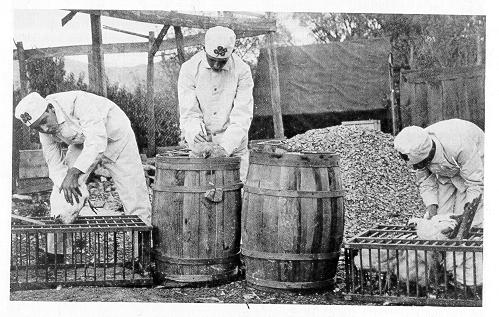

A Berks County 4-H poultry judging team, typical of the youth groups organized by county agents, demonstrates "caponizing."

For all of its industrial development, Pennsylvania still ranked sixth in the nation in the value of its agricultural products during the 1920s and had within its borders over 200,000 farms. Agricultural extension was thus very important, although it did not reach nearly so many students in formal educational situations as did engineering. In fact, the School of Agriculture had nothing comparable to engineering's permanent branch schools. Persons desiring formal instruction in agricultural subjects had the options of enrolling in a two- or four-year program at the College, taking correspondence courses, or attending short courses given at the College in mid-winter and mid-summer.

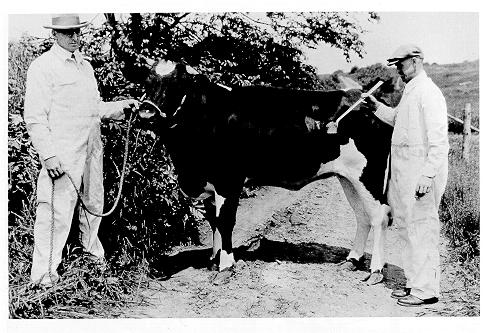

Professor Samuel I. Bechdel and James F. Shingley with Pennstate Jessie.

In 1926, in an experiment that attracted international attention, researchers in the School of Agriculture made a fistula or hole in Jesse' stomach, from which they extracted—with no apparent discomfort to the animal—partially digested food for pioneering studies concerning animals' vitamin requirements.

One the other hand, through informal contacts, agricultural extension reached an estimated 100,000 Pennsylvanians annually, mainly through the activities of the county agents. By 1925, 65 of Pennsylvania's 67 counties had full-time extension agents who worked in cooperation with extension specialists of the academic departments in the School of Agriculture. In some states having similar organizations, ill feeling arose between the agent and the specialists, as each group vied for control of extension projects and the attention of farmers. In Pennsylvania, where Milton S. McDowell directed agricultural extension, the emphasis was on cooperation instead of competition. "It was felt that the individual who had been specially trained in a particular line of activities and who was constantly in touch with the experiment stations, which have always been recognized as the source of correct information, should be responsible for the correctness of the facts which were being taught by the county agent," McDowell explained. "The aim was to have the county agent look to the specialist for guidance on subject matter; also that the specialist would give the county agents assistance in planning and carrying out their programs." The agents had the primary responsibility for transferring information from specialists to practicing farmers. They were residents of the communities they served and, unlike the specialists, who were based in State College, were in continuous contact with farmers and were well acquainted with their needs and viewpoints.

McDowell and the county agents believed that local conditions should determine the nature and content of extension work as much as possible. An agriculture extension association, a public body composed of farmers and other interested citizens, was organized in each county to determine, in consultation with the agent, what kinds of extension work would be carried on there. Agents, in turn, were answerable only to Director McDowell, whose preference for decentralization often brought Penn State into conflict with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the agency charged with disbursing the money the federal government provided under the Smith-Lever law. In some states, notably those in the South, the USDA exercised a considerable influence over the formulation of extension projects, on the unwritten principle that control follows funds. This was not the case in Pennsylvania, which ranked second or third in money received through the Smith-Lever Act but nevertheless had one of the most independent extension programs of any state.

The first home economics extension agents, 1917. Within a decade, their number had increased to twenty-five and agents were being assigned to individual counties.

Because of the depressed market for many agricultural products during the 1920s, farmers were interested in finding ways to lower their costs of production and raise their incomes despite low prices. A case in point involved the dairy industry. The average Pennsylvania cow produced about 4,000 lbs of milk every year. County agents, in cooperation with local citizens, established some fifty demonstration projects which showed farmers how they could boost annual production to an average of 7,500 lbs. The extension service was not trying to increase overall production but rather to encourage farmers to maintain current production levels using fewer cows, thus reducing expenses. For that same reason, county agents provided information on such topics as crop storage, transportation, and farm accounting and bookkeeping. A Department of Agricultural Economics was founded in 1923 in order to help farmers become better acquainted with the workings of the marketplace.

Aside from their teaching roles, county agents and faculty in the School of Agriculture were in great demand as judges and speakers at county fairs and agricultural gatherings across the state. The agents were active in organizing 4-H Clubs to promote careers in agriculture among the Commonwealth's youth and regularly wrote newspaper columns and gave radio talks summarizing the latest findings of the experiment station or spotlighting how new knowledge gained through extension had improved agricultural practices.

The agricultural extension service also exercised administrative jurisdiction over the extension programs of the Department of Home Economics. With the exception of a few correspondence courses, extension education in home economics was informal and was carried on by a small staff of field representatives, each of whom was assigned a territory of two to five counties. These representatives typically gave talks and demonstrations on meal planning, clothing construction, food preservation, and similar subjects-mostly to women's groups-and reached an audience of nearly 10,000 persons a year by the end of the decade. A growing number of public elementary and secondary schools were calling upon the home economics extension staff to act as nutritional consultants in planning school lunch menus and in giving presentations directly to children on proper eating habits. Extension specialists also offered, whenever requested, a series of short courses to teachers of home economics at the high-school level.

Two other schools of the College sponsored extension services: Education and Mines and Metallurgy. As Will Chambers had foreseen, extension fulfilled an important need for public school teachers. The Department of Teacher Training Extension in most years enrolled more than twice as many students (including the summer session for teachers) as the engineering evening schools and accounted for 60 percent of all students taking formal non-correspondence instruction through the College's extension services. In addition to permanent centers in Pittsburgh and Harrisburg, education extension courses-for college credit-were held at convenient locations wherever twenty or more students gathered.

Extension work in the School of Mines and Metallurgy was confined to the coal-mining industry. Like nearly everything else connected with the school, mining extension was severely handicapped by a lack of financial resources and an absence of encouragement from state government and mining industry officials. Mining extension representatives did participate to a limited extent in a series of evening schools sponsored by the state Departments of Mines and Public Instruction in both the anthracite and bituminous regions. One aim of these classes was to help miners pass state licensing tests for more responsible positions, such as fire boss and shift foreman. The School of Mines and Metallurgy also sponsored a few short courses for mine superintendents and other supervisory personnel during the summer months. No college credit was attached to any work in mining extension, nor were correspondence lessons offered.

Agriculture, together with home economics, was the only branch of extension that received federal financial support (through the Smith-Lever Act) as well as direct appropriations from the Commonwealth. Presidents Sparks and Thomas had repeatedly urged the General Assembly to make specific allocations for non-agricultural extension, and land-grant educators across the nation made similar pleas to Congress; but neither effort met success. Predictably, the relative affluence of agricultural extension caused some internal friction at Penn State. "It became the common idea that agricultural extension had more money than it needed," wrote Milton McDowell. "This, of course, was not true, but there was jealousy in some quarters. Some department heads in the School of Agriculture, as well as in the College administration, cast longing eyes toward securing some of this money."

Under federal law, McDowell, as extension director, had to approve all Smith-Lever expenditures. He argued that these funds could be legally spent only on agriculture and even then only on those projects that were directly related to extension, as differentiated from agriculture research or miscellaneous uses. Others among the College faculty contended that at least the matching funds the Commonwealth provided under Smith-Lever could be used for non-agricultural extension work and regarded McDowell as an obstacle to distributing funds more equitably. President Thomas proposed combining all non-agricultural extension services under a single director, which some observers believed was intended as the first step in marshalling internal political support for a drive to wrest a portion of extension money from McDowell's jurisdiction. But too many deans opposed unification, fearing loss of authority over their respective programs. Thomas' plan came to nothing.

Ralph D. Hetzel

THE QUIET LEADERSHIP OF RALPH HETZEL

The histories of colleges and universities are frequently divided into eras that coincide with presidential administrations. A change in the administration of an institution of higher learning can bring with it vast changes in the operation and character of the institution itself, but this did not occur in the transition of leadership from President John M. Thomas to his successor, Ralph D. Hetzel. To be sure, Hetzel's personal style differed markedly from that of Thomas and in that respect the change of leadership was an abrupt one. Yet aside from quietly putting to rest the notion that Penn State ought to become a university in name as well as in fact, Hetzel shared essentially the same goals for the College as his predecessor.

Their experiences with Dr. Thomas convinced the trustees that the College required a leader who not only had compiled a distinguished administrative record, but one who was thoroughly acquainted with land-grant education and had experienced the give and take of the political arena. Ralph Dorn Hetzel possessed these qualifications, and in September 1926 he was selected to become Penn State's ninth president. The 43-year-old Hetzel had spent his entire career in the service of land-grant schools. Born in Wisconsin, he had completed undergraduate work at the University of Wisconsin in 1906 and remained there two more years to study law. In the meantime, he developed a great interest in higher education. No sooner had he received his law degree than he accepted a position as an English instructor at Oregon State College, another land-grant institution. There he taught English and political science until 1913, when he was named director of Oregon State's extension services. His record of accomplishment in that post was sufficient to bring him to the attention of the trustees of still another land-grant school, the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, whose presidency Hetzel assumed in 1917.

If New Hampshire College ranked as one of the nation's smaller land-grant institutions, it nevertheless faced some very large problems. Its enrollment-barely 450 students when Hetzel took office-was inordinately low even in a state with a small population. Its physical plant was inadequate in size and poorly maintained. It had no widespread base of popular support, a weakness reflected in its annual state appropriations, which totaled only $48,000 in 1917. New Hampshire's farm population had shown an interest in the school, but many farmers were against significant change in its organization for fear that agricultural work would lose priority. Two attempts to change the name of the college to the University of New Hampshire failed primarily because of the opposition of agricultural interests. After the dislocations brought on by World War I were over, Hetzel began working to rally public confidence in the institution. One the one hand, he strengthened the arts and sciences to attract more students and give a better balance to the curriculum; and on the other, he assured farmers that agricultural education and research would continue to have an important role. Graduate work and summer sessions were introduced. In 1923 the college was able to rename itself the University of New Hampshire, a sure sign of the success of Hetzel's program. By the time he left for Penn State, the student body numbered over 1,300, and legislative appropriations were averaging a half million dollars per year.

Hetzel came to Penn State because he believed he had accomplished what he set out to do at New Hampshire, and thus the time had come to search for a new challenge. "I became convinced that here was the greatest opportunity for constructive educational work that could be found in all of these United States," he explained upon taking up his new duties in Pennsylvania. "I felt that I had one more good scrap in my system and that here was an opportunity to work it out." If Hetzel figured to follow his predecessor's lead. and get into a scrap with the Commonwealth's political leaders, he gave no sign of this intention in his inaugural address, presented at the June 1927 commencement. He announced no grandiose plan for expansion, painted no vivid picture of the future of the institution, and did not even disclose any specific objectives for his administration. He carefully skirted the issues of university status for Penn State and the penurious policies of past governors. The speech was in keeping with the new president's personality. Modest, unassuming, kindly, and yet intensely earnest in his own gentle way, Ralph Hetzel was not one to jump blindly into things. He preferred a more studied approach and wished to familiarize himself with the College and the prevailing political winds in Pennsylvania before committing himself to a course of action.

Hetzel did not have to ponder long before deciding what his first order of business must be. He confessed to the trustees that, as a candidate for the College's presidency, what had made the most lasting impression on him was the "extreme depletion of the physical plant," which he described as "inadequate in size, and at points exhausted, and in part unfit and dangerous for occupancy." Hetzel was prepared to give a high priority in the new administration to construction because physical expansion was fundamental to anything else the College might do to meet the growing demand for higher learning.

En route to building dedication ceremonies are (far left) board of trustees president J. Franklin Shields, architect Charles Z. Klauder, President Hetzel, and Governor John S. Fisher.

Many people concurred with this view, including Pennsylvania's new governor, John S. Fisher. From the first, the Republican Fisher showed himself to be far more supportive of the needs of Penn State and higher education in general than Gifford Pinchot had even been. He had been a professional educator before turning to the law and business (and eventually politics) and had sat as a representative of the industrial associations on the College's board of trustees since 1923. By itself the governor's good will could do little for Penn State. Backed by a handsome surplus in the state treasury and a prosperous economy, it was enough to convince the General Assembly in May 1927 to give the institution $4 million for the forthcoming biennium. One million dollars of that amount-the largest allocation the Commonwealth had yet made to the College-was to be spent on new buildings.

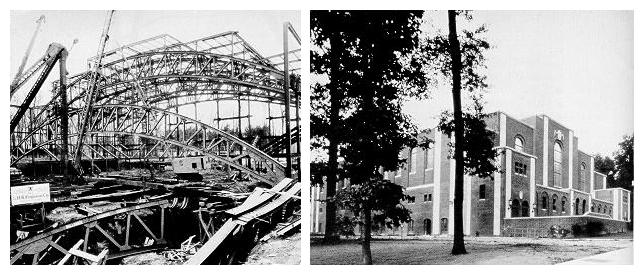

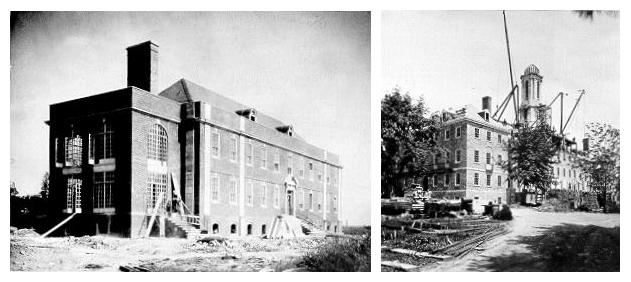

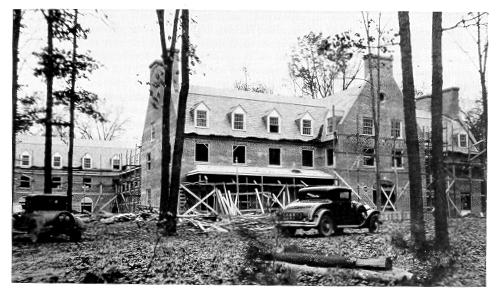

Financed by state funds or money accrued from the Emergency Building Fund campaign, construction was under way or about to begin on six major structures by mid-1928: a new main engineering building to replace the one destroyed by fire over a decade before; a recreation building capable of seating 7,000 persons to supersede the antiquated Armory; Grange Memorial Dormitory, offering living accommodations for 100 female students; an infirmary; a third men's dormitory as a companion to Watts and Varsity halls; and the first unit of a new biological sciences building. In addition, work had already been completed on a spacious new service building, which for the first time provided a central location for the College's general stores and maintenance shops. Plans also called for the erection of a north wing to Pond Laboratory and an extensive remodeling of Old Main, a necessity if the decrepit structure was to continue to serve any useful purpose. The general architect was Charles Z. Klauder, who selected a modified colonial Georgian style for most of the new structures. Total funds authorized for the expansion program amounted to $1.8 million.

Meanwhile the state of the proposed Penn State bond issue, a legacy of the Thomas administration, was to be decided at the general election in November 1928. The referendum, if approved, would allow the raising of even more money for buildings. The College consequently mounted a vigorous publicity campaign, urging voters to cast their ballots in favor of the bond issue. Coordinating the campaign was E. K. Hibshman, a field organizer during the previous fund drive whom Hetzel had put in charge of public relations. Hibshman supervised the distribution of a barrage of news releases, informational pamphlets, WPSC radio broadcasts, movies, and similar materials, while alumni, current students, and their families were asked to go door-to-door to convey Penn State's message personally to as wide an audience as possible. The campaign peaked in late October with the publication of 1.5 million "Give your vote" folders and the issuance of seven prints of a new film on what Penn State meant to Pennsylvania. Not letting any opportunity pass, Hibshman also made arrangements with a commercial bakery to enclose Penn State's promotional literature in the wrappers of tens of thousands of loaves of bread.

Buildings under construction in the late 1920s and early 1930s included (top photos) Recreation Hall (framework and completed building); the new infirmary, later named Ritenour Health Center (above, left); "new"' Old Main (above, right); and the Nittany Lion Inn (below).

No organized opposition appeared against the bond issue campaign, which carried the endorsements of the Pennsylvania State Education Association, the American Legion, the Pennsylvania Retail Merchants Association, and a host of other business and civic groups. Nevertheless, Governor Fisher declined to take a clear-cut stand on the referendum, preferring to sidestep the question by making vague promises to assist the College in any way possible. Auguring far worse for the bond issue's future were the statements of outgoing state Treasurer Samuel S. Lewis and Auditor General Edward Martin (who was a candidate for Lewis's office and one day would become governor in his own right). Both men repeatedly declared, without contradiction from Fisher, that the Commonwealth need not go into debt for Penn State nor for any of the four other bond issues on the ballot-proposals for a reforestation program, expanded highway construction, new National Guard armories, and new buildings for normal schools and state-owned institutions. Pennsylvania's treasury, Lewis and Martin assured voters, contained ample funds to support all of these endeavors.

On November 6, 1928, Pennsylvanians went to the polls and rejected all five bond referendums. The Penn State proposal received more votes than any of the others and lost by only 26,000 of about one million votes cast. Most political observers did not construe the defeat of the bond issues to mean that the voters rejected the worthiness of the needs for which the bond money was to be spent. "There can be no doubt that the bond issue proposals submitted in the recent election were in the main defeated on the word of state fiscal authorities," explained the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, in a November 15 editorial, "which imposes a specific obligation upon those who defeated the bond amendment proposals to join now in the movement to obtain from the coming session of the legislature appropriations sufficient to meet the needs adequately upon the pay-as-you-go basis."

Governor Fisher needed no prompting to recognize his obligations. A series of fiscal reforms instituted during the Pinchot administration placed the burden for drawing up a tentative biennial budget for the Commonwealth on the governor's office, thus doing away with the former system whereby state agencies-and Penn State-submitted their budget requests directly to the General Assembly. Fisher's budget for 1929-31 contained $6.3 million for the College, $2.25 million of which was for new building construction. With the large positive response to the Penn State bond referendum fresh in their minds, the legislators approved the entire amount recommended by the governor. The Penn State appropriation was only a small part of some $39 million that the lawmakers authorized for the erection of new buildings at many state-owned or state-related institutions, including the normal schools, which Fisher was gradually transforming into state teachers' colleges, complete with baccalaureate curriculums.

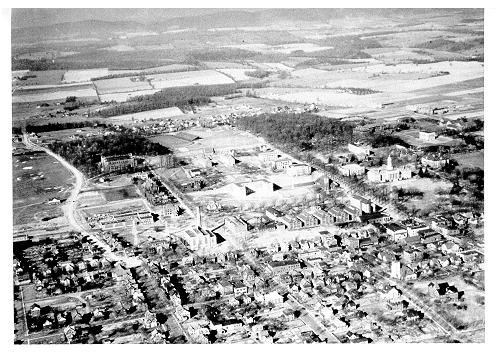

The campus about 1931

In June 1929, Penn State's board of trustees gave formal approval to the next stage of the building program. The new structures were to consist of a mineral industries building, a home economics building, a north wing for the liberal arts building (leaving the central or connecting section to be built at a later date), a new campus power plant, and various agricultural barns and sheds. At an earlier meeting, the trustees had heard reports from Charles Klauder and other consultants that the walls of Old Main were too weak to permit any substantial renovation of that structure and so had given reluctant approval to proceed with total demolition. A new Old Main was to rise on the site of its predecessor, following the same general architectural style and incorporating wherever possible the stone of the original structure, even to the point of using the same stone from the corners of the old building in the corners of the new. Although the "new" Old Main had only four floors compared with five in the "old" Old Main, it had much more usable space. It housed not only most of the College's administrative offices, but also offices for the Alumni Association, meeting rooms for student groups, a student lounge, and offices for student publications and student government. Completed in 1930 at a cost of $837,000, it was the most expensive structure thus far erected at Penn State. Rounding out the second phase of the building program was construction of the Nittany Lion Inn, a dining and hotel facility opened in 1931 and financed by a private loan of $350,000. The community of State College had no first-class hotel to accommodate visitors attending conferences, athletic events, graduations, and other campus events; the Inn was a belated attempt to rectify this problem.

The great building program of the late 1920s can be considered the first major achievement of Ralph Hetzel's presidency. Between 1927 and 1930, $4.5 million was spent on buildings, compared with $2.8 million over the previous seventy-two years. Yet these vital improvements to the physical plant can also be viewed as the climax of a great effort begun at the outset of the decade under the leadership of John Thomas. That the College's physical plant grew so dramatically during the late 1920s was due primarily to the accumulation of money from the Emergency Building Fund campaign, the election of a governor well disposed toward Penn State, and the general prosperity of Pennsylvania's economy. Hetzel's arrival at the College was as propitious as his predecessor's had been ill-timed.

ATHLETIC POLICIES REFORMED

Another campaign of sorts that had its beginning early in the decade but reached its zenith during the first few years of the Hetzel presidency concerned what contemporary observers delicately referred to as "the athletic situation." Intercollegiate athletics had become immensely popular with students, alumni, and the general public by the 1920s. The activities of intercollege sports teams received more attention from the press than did the academic side of higher education, and football solidified its position as the preeminent sport of America's institutions of higher learning. In 1927, thirty million spectators paid $50 million for tickets to intercollegiate football contests. Gate receipts from football allowed some schools to finance the less popular and less remunerative sports or, in a few cases, to pay for non-athletic endeavors. For those colleges and universities which made little or no money directly from football, the game still had great promotional value. A perennially powerful football team could help a school make itself better known to the public and build up a large grass-roots following, a useful asset to any institution in times of financial need-which for most was just about all the time.

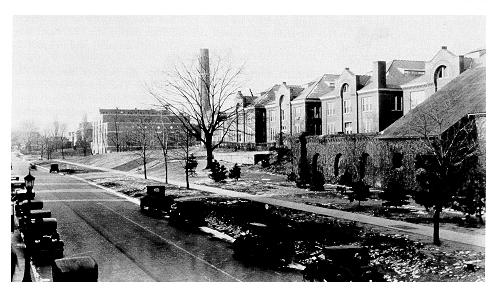

Looking west past the engineering units toward the new power plant. College Avenue had been paved (with brick) only a few years before this photograph was made, about 1930.

Thus there was nothing unusual about John Thomas writing an essay on "Why I Believe in Football" for the October issue of Penn State Pictorial, a periodical developed for use in the Emergency Building Fund campaign. "I believe in football because it fuses the College into a unit," declared Dr. Thomas. "Before the first big home game each year, the College is only a mass of individuals, but with the long yell that greets the team for its first big fight, a new and living entity comes into being. In the game the soul of the College is awakened anew, and he is no man at all into whose heart the thrills of the contest do not send currents of devotion and loyalty which will flow till his heart no longer beats." To help stimulate currents of devotion and loyalty among the public at large, Thomas in 1923 approved the creation of the full-time position of sports publicity director within the College's Department of Public Information. Five years later, broadcasts of home football games began over radio station WPSC, with sophomore Kenneth Holderman calling the play by play. Football brought in by far the largest income of any of the ten to twelve intercollegiate sports at Penn State during the 1920s and was the only sport to show a profit. Gross receipts averaged over $100,000 annually and net profits sometimes exceeded $50,000.

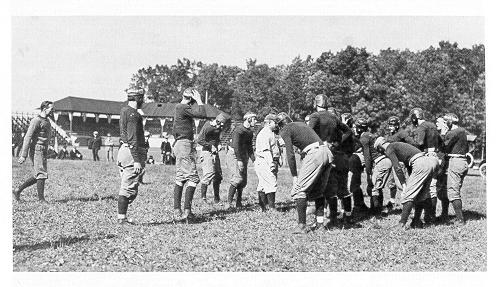

Hugo Bezdek (center, in white) supervises football practice on (new) Beaver Field.

By the 1920s control of intercollegiate athletics had passed from the student body to the alumni at most larger colleges and universities, including Penn State. The alumni-dominated Athletic Advisory Committee, created during the reorganization of the Athletic Association in 1908, within a few years came to exercise nearly undisputed authority over the hiring and firing of coaches, the creation of schedules, and most other phases of athletic policy. Under this arrangement, the football team compiled an exceptionally fine record, winning 40 games and losing 10 between 1919 and 1924, a period which also included two undefeated seasons (1920 and 1921) and an appearance at the 1923 Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California.

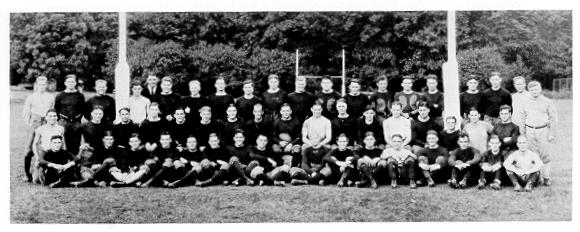

1923 Rose Bowl Squad. Coach Bezdek stands at far right.

Much of the credit for this impressive performance went to head coach Hugo Bezdek. Bezdek drove his players hard and did not hesitate to crack the whip over them. He was well known for the public scoldings he gave team members who he felt had not given a total effort and for his habit of practicing the entire squad for several hours immediately following a losing game. "I work the boys hard," he once said in explanation of his frequent and often bloody scrimmages, "so that the actual Saturday games will, by comparison, be child's play." Bezdek was adored by the student body if not by his players. His worth to the College, as measured by the Thomas administration, was clearly evident by the handsome $14,500 salary he was earning, which nearly equaled what the trustees agreed to pay incoming President Hetzel and was three to four times greater than the salaries of most professors.

Bezdek's popularity began to wane in 1925. That year marked the fourth consecutive defeat his team had suffered at the hands of the squad from the University of Pittsburgh, a series of losses that had caused considerable embarrassment among prominent members of the Pittsburgh Penn State Alumni Club. After the 1925 season, leaders of the Pittsburgh alumni club formed what they called a "College Relations Committee" to determine if and how Bezdek could be relieved of his Job. The committee made its recommendation at the annual meeting of the Alumni Association in June 1926. The Pittsburghers called for the replacement of the Athletic Advisory Committee with a new athletic council, which would be even more under the control of alumni than its predecessor. Coaches of intercollegiate teams were to be ineligible for a seat on the council, a feature designed to prevent Bezdek from having any influence on policy matters and thus make the task of ousting him much easier.

The Alumni Association also heard a request for a review of basic athletic policies, a request that did not stem from any dissatisfaction with the failure of the football team to beat Pitt. On the contrary, a growing number of alumni believed that Penn State had been placing too much emphasis on football and neglecting the development of a program of physical education for all students. Many of these critics had no more use for Hugo Bezdek than did the Pittsburgh dissidents. They claimed that while Bezdek had been appointed to implement a diverse offering of intramural sports in which the entire student population could participate, he had directed his energies not toward acquiring equipment and faculty for intramurals, but rather on the construction of Varsity Hall, which benefited only those students who were intercollegiate athletes. Undue emphasis on football also contributed to its professionalization, corrupting the traditional ideals of amateur athletics. A higher degree of perfection was demanded on the athletic field, it seemed to these critics, than in the classroom or laboratory.

Among the alumni who believed the College's athletic policy needed to be revised were Edward N. "Mike" Sullivan, since 1919 the executive director of the Association and editor of Alumni News, and James Milholland, incoming Association president. Sullivan pointed out that the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching was launching a comprehensive investigation of athletics at the nation's colleges and universities. By conducting its own study, Penn State could eliminate abuses that the Carnegie report was likely to single out and thus put itself in the forefront of those institutions working to "clean up" intercollegiate sports. Support for Sullivan's argument was already widespread. The Athletic Advisory Committee had already reduced the number of athletic scholarships Penn State awarded from 75 to 50. Accordingly, the Alumni Association created a committee chaired by engineer and businessman John Beaver White '94 to survey the College's athletic policies and to make suggestions for their improvement. The formation of this committee temporarily placated members of the Pittsburgh alumni club, who may have allowed their desire to oust Bezdek to obscure the more far-reaching changes that White and his colleagues were likely to recommend.

The Beaver White committee, as it was commonly known, began its work in the summer of 1926 and met with a large number of faculty, alumni, and friends of the College. It did its work without fanfare, almost secretly, and although some students were interviewed, most were unsure of what was happening. "What the student body wants to know is this: Just what, if anything, is wrong with Penn State football?" asked a Collegian editorial on October 26. "Will the alumni who think there is something wrong with football, come to the students and tell us just what that something is?" Several months passed before the students got a satisfactory response. In March 1927, the Beaver White committee reported its findings to a meeting of the Alumni Association's board of directors.

The report contained four main recommendations, all aimed at reducing the emphasis on intercollegiate athletics and stimulating the growth of intramurals. First, the Athletic Advisory Committee should be disbanded in favor of a Board of Athletic Control to be composed of one College trustee, four faculty, five alumni, and three students. Second, the practice of offering athletic scholarships should be abolished. "Your committee has become convinced that the present general system of athletic scholarships and financial help to athletes, in vogue in many collegiate institutions, is neither a credit to, nor in the best interests of, the institutions or good sportsmanship," stated the report. Without giving specific figures, it claimed that at Penn State and many other schools, holders of athletic scholarships too often withdrew before graduating, while the general policy of extending athletic scholarships discouraged the further athletic development of those students who were not fortunate enough to receive them. The third recommendation urged that all intercollegiate activities be supervised by the new Board of Athletic Control and that the Department of Physical Education, which the Beaver White committee hinted should be given the status of a school, should have responsibility for intramurals or mass athletics. To insure that intramurals received the attention they deserved sound bodies were as important as sound minds-the director of the physical education department should not be permitted to coach any of the intercollegiate squads. Finally, the Beaver White committee recommended that a new method be used to nominate alumni representatives for the Board of Athletic Control. Alumni members of the Athletic Advisory Committee were nominated by a special panel chosen by the board of directors of the Alumni Association, then voted on by the general membership. To make this process more democratic, it was suggested that the name of any alumnus nominated by 25 or more of his fellow alumni should be placed on the general election ballot.

The Alumni Association decided to take the recommendations of the Beaver White committee directly to the alumni (at least those residing in Pennsylvania) before acting on them. Meetings were held in early April at five locations across the Commonwealth; alumni were invited to read the Beaver White report, offer their own views, and then vote on whether to accept each of the four recommendations. Critics of the proposed reforms later charged that inasmuch as the contents of the Beaver White document were not released prior to these meetings and that Sullivan, Milholland, and White himself were present at most of these one-day sessions to speak forcefully in favor of the changes, the results of the alumni balloting were meaningless. Sullivan announced in the May issue of Alumni News that over 90 percent of voting alumni approved of all of the Beaver White recommendations except the one that advocated eliminating athletic scholarships, which received approval from 77 percent of alumni. He did not disclose what percentage of the Alumni Association membership turned out for these meetings.

The next step was to obtain the consent of the students to amend the Athletic Association constitution to permit the establishment of the Board of Athletic Control. According to that constitution, 40 percent of the student body had to vote on the referendum and two-thirds of the votes cast had to favor the amendment. Students were not voting directly on the question of athletic scholarships, although they must have known that the Board of Athletic Control, should it come into existence, very likely would eliminate them. For all their interest in football and other intercollegiate sports, and in spite of the fact that the alumni had kept them in the dark much of the time, the students were willing to go along with the proposed changes. Perhaps the Collegian mirrored the thoughts of most students when it proclaimed in an April 26 editorial, "The time is soon coming in collegiate athletics when the scholarships will have been abolished entirely. . . . Should Penn State be a pioneer in this movement, it would mean more to her esteem and name than to harbor an entire football team of All Americans." Of 1,290 votes (representing 60 percent of the student body) counted in a May 9 referendum, 1,065 approved amending the Athletic Association's constitution to allow the Board of Athletic Control to succeed the Athletic Advisory Committee.

The new board met for the first time in August 1927, and, as expected, agreed to discontinue granting athletic scholarships effective with the class entering in the fall of 1928. All current scholarship contracts were to be honored, so not until 1931-32 would the College be free of the "taint" of subsidized athletics. For the public record, Hugo Bezdek favored the board's action and, in fact, all the recommendations of the Beaver White committee. His private opinions may not have coincided precisely with his official views, yet they could not have been too greatly at variance. At the same meeting of the Board of Athletic Control at which athletic scholarships were abolished, for example, a motion was made that the College should send no scouts to teams that agreed not to scout Penn State teams. At Bezdek's insistence, however, the board voted to eliminate the practice of scouting altogether, regardless of the policies of opponents, on the grounds that it had overtones of professionalism. And contrary to the allegations of many of his critics, Bezdek did display a commitment to broaden athletics to benefit the majority of the student population. So far during his tenure as head of the Department of Physical Education, new tennis courts, a skating pond, an 18-hole golf course (later the White course), and several intramural fields were added, with construction about to commence on the long-awaited Recreation Hall. Hugo Bezdek had also been, along with Dean of Men Warnock, one of the prime movers behind the abortive Penn State Student Union, one of whose principal objectives was to expand the intramural sports program.

The phasing out of athletic scholarships caused remarkably little reaction among the students. The Collegian saw fit to comment on the matter only once as the fall semester got under way, and its words echoed the spirit of those alumni who wanted to make intercollegiate sports more moral. "What care we about the wins and losses as long as the team gives its all and is a credit to the old alma mater," asked the paper in a gush of idealism in early September. "The results of the successive contests should rank last in importance. What matters is whether the team displayed all the pluck, courage, and aggressiveness of which it is capable. If it did that, it played championship football, win or lose."

Members of the faculty and administration had heretofore limited themselves in most instances to being interested spectators in what was generally regarded as an alumni affair. The College Senate cooperated with the Beaver White committee investigation and endorsed its findings, and Ralph Hetzel lent encouragement to those alumni who wished to root out the professionalism in intercollegiate sports and build up a program of "athletics for all." Hetzel also desired, in the interest of protecting the purity of amateur athletics, to transfer control of intercollegiate athletics from the alumni to the administration. He saw an opportunity to accomplish this when the Pittsburgh alumni club renewed its efforts to get rid of Coach Bezdek. Club members were asking for a quick adoption of the third recommendation of the Beaver White committee, the one calling for the head of the physical education department to divorce himself from involvement in intercollegiate athletics. If Bezdek could not be fired outright, at least he could be rendered powerless over the football team.

The trustees responded by appointing a three-man committee chaired by Jesse B. Warriner '05 to consider what action should be taken. In its report to the trustees in June 1929, the Warriner panel tried to steer a middle course. Noting that the Pittsburgh alumni's complaints were "based principally on the annual overwhelming defeat of the football team by the football team of the University of Pittsburgh," it nonetheless concluded that their complaints should be given "careful consideration and full discussion" — not by trustees but by the Board of Athletic Control.

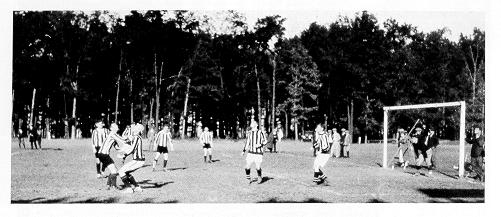

Intercollegiate soccer contests, part of the Penn State sports scene since 1911, during the 1920s were held adjacent to Beaver Field.

The Warriner report came before the Board of Athletic Control on January 9, 1930. President Hetzel attended the session and made a strong plea for the board to put intercollegiate athletics under the authority of the Department of Physical Education, whose head would henceforth be prohibited from serving as a coach. Bezdek was also present and seconded the president's suggestion, saying that he was prepared to relinquish his duties as football and baseball coach should he be asked to continue as head of physical education. The board agreed to Hetzel's request, adding that it believed the Department of Physical Education should be elevated to the status of a school and that Bezdek should be its director. (Curiously, the more appropriate title of "dean" was never mentioned.) The College's trustees were the next group to consider the matter, and at their meeting on January 20 they created the new School of Physical Education and named Bezdek director. "We do not expect to lessen emphasis on intercollegiate participation in our dozen organized sports," said a smiling Ralph Hetzel after the meeting, "but rather to supplement this activity with an extensive program of play and physical education which shall touch every student of the College.

Hetzel had a right to be pleased: The Board of Athletic Control had just written itself off as a dominant force in Penn State athletics. Although it was to linger on for many years, it was to be more purely advisory than the old Athletic Advisory Committee it replaced. Most power in athletics now rested with the administration, since intercollegiate sports came under the jurisdiction of the School of Physical Education and the School's director was answerable to the president.