4

Toward a State University

As it began its second half-century, The Pennsylvania State College was more typical than unique among land-grant colleges and universities, though to be sure, its peculiar legal relationship with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania had no exact parallel in any other state. It was the national leader in engineering extension education and the establishment of technical institutes, and a few of its curricular offerings were not generally available elsewhere. In its agricultural activities, it certainly had no counterparts among Pennsylvania institutions. But in the trend toward curricular specialization, the emergence of student government, the belated attempt to give more prominence to the liberal arts, and numerous other broad aspects of its development, the College was in the mainstream. What it had in common with other land-grant schools far outweighed any differences.

IN THE MAINSTREAM OF LAND-GRANT EDUCATION

Land-grant colleges and universities, for example, were thoroughly middle class institutions, and Penn State was no exception. A survey conducted by registrar A. Howry Espenshade revealed that of some 1,800 undergraduates and two-year agricultural students in attendance in 1913-14, about 60 percent said their fathers were engaged in mercantile, commercial, professional, or other endeavors that could be defined as typically middle class. Only 18 percent characterized their fathers' occupational field as agricultural, while another 18 percent described their fathers as artisans or laborers. Espenshade did not differentiate between undergraduates and students in the two-year courses. If he had, the proportion of undergraduates whose fathers were employed in middle-class positions would presumably have been much greater than 60 percent, since the two-year students were more likely to come from farm households.

Another characteristic of land-grant schools (and most institutions of higher education) was low pay for faculty. Few colleges, least of all those heavily dependent upon state support, paid salaries commensurate with their teachers' academic training and responsibilities. Inadequate compensation had been a source of dissatisfaction among the Penn State faculty for decades. Once the Commonwealth began increasing its appropriation to the College under President Sparks, the issue became a serious point of contention between the teaching staff and the administration. Many faculty at first believed that they had found an ally in Dr. Sparks. Soon after his arrival, he decreed that the College pay its teachers monthly rather than in the semiannual installments they had received under Atherton. Under the old system, many teachers ran short of cash during the six months between installments and often had to borrow funds at interest from local banks, thereby decreasing their meager salaries still further.

The good will Sparks won by instituting monthly pay periods evaporated when no significant pay raises followed over the next few years, years which witnessed the first prolonged period of inflation the nation had experienced since the Civil War. Compensation remained dismal; in 1915 average annual salaries ranged from $1,984 for a professor to $1,014 for an instructor. Averages did not tell the full story, however: Salaries were higher in the technical fields, where they had to be in order to compete with private enterprises, but were correspondingly. lower in other fields. Dean Samuel Weber complained that a June graduate of the School of Agriculture could return that fall as an instructor at a higher salary than that given to department heads in liberal arts. But even professors of agriculture and engineering earned substantially less than they could if employed in business and industry.

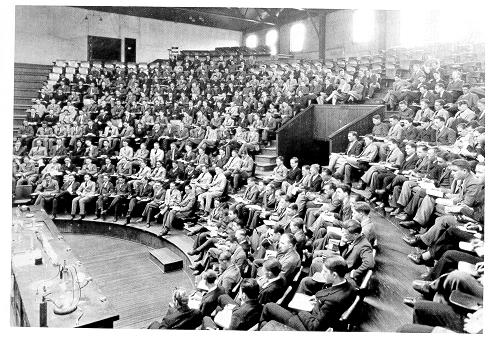

Nor did the faculty find much relief from what they claimed were burdensome work loads. The number of teachers had risen from 117 to 214 between 1908 and 1915; the undergraduate population had grown from 909 to 2,017 during this same interval. Class sizes continued to grow larger, and the need for more instructors intensified. In the School of Engineering, it was not unusual for a professor to be assigned two different classes, meeting simultaneously in two different rooms, sometimes even in separate buildings. Only by utilizing student assistants, occasionally graduate students but more often seniors, could the professor teach both groups. Under such makeshift arrangements the quality of education inevitably suffered.

Some faculty accused Sparks of being more interested in constructing buildings and improving Penn State's public image than in elevating the quality of undergraduate education. The president's comment, made in a report to the trustees on the financial condition of the College, that "our present motto must be 'as few instructors as we can possibly get along with, for the least possible compensation,' " did nothing to assuage the discontent of the teaching staff. Under such circumstances a high turnover in personnel was to be expected. Of the 117 persons who comprised the faculty in 1908-9, only 44 remained seven years later.

Like other rapidly growing colleges and universities, Penn State faced the formidable task of supplying its students with an increasing variety of administrative and support services. The absence of adequate health care, for instance, had presented a problem for many years. Students needing hospitalization had to be transported twelve miles to Bellefonte, and the student body had grown so' large that reliance on local physicians in Private Practice was no longer practical.

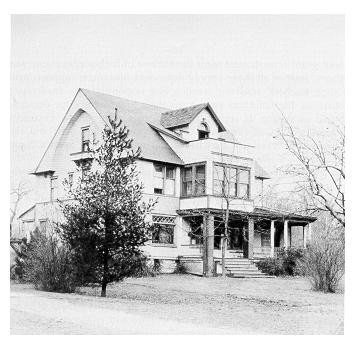

Ilhseng House, first College infirmary.

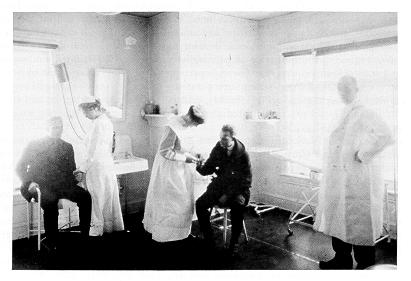

After an outbreak of scarlet fever in 1912-13, the College began soliciting private donations for the construction of a hospital. While the Sparks administration believed that the amount thus raised ($5,000) was insufficient to finance such a project, it did secure in 1914 a full-time physician, Dr. Warren E. Forsythe, formerly of the University of Michigan. Dr. Forsythe supervised the conversion of IhIseng House (a ten-room faculty residence formerly occupied by Magnus C. IhIseng of the School of Mines) into an infirmary that opened in January 1915. During their first year, Dr. Forsythe and his staff of two registered nurses handled over 11,000 patient visits, about 200 of which resulted in overnight stays in one of the infirmary's six beds. Students suffering from contagious diseases continued to be cared for in the isolation ward, or "pest house" as it was popularly known, a section of the old "Bright Angel" dormitory that had been moved to a wooded site near New Beaver Field during the scarlet fever epidemic. Each student was assessed one dollar annually to pay for the new health service, which was soon expanded to include physical examinations for all incoming freshmen. Forsythe resigned in 1917 and was succeeded by Dr. Joseph P. Ritenour, a 1901 graduate of Penn State and a former general practitioner in his native Fayette County.

The College's business officers performed less visible but equally important services. The centralization of all fiscal responsibilities in the treasurer's office had not produced the expected efficiencies, so in 1917 the trustees authorized the creation of the post of comptroller and the following year approved the appointment of Ray H. Smith, then secretary-treasurer of the Alumni Association, to this office. Smith had many of the same duties as the old business agent, including representing the College in all financial dealings and managing all property. His most important action initially was to name a superintendent of buildings and grounds, Roy I. Webber of the Department of Architectural Engineering, and put under his authority the maintenance of the College farms (formerly under the jurisdiction of the School of Agriculture) and the campus light, heat, and power systems (heretofore supervised by the School of Engineering). Webber also had charge of the operation of the sewage disposal plant the College had recently constructed, by order of the Pennsylvania Department of Health, near Thompson Spring on the eastern edge of the campus. It shared this new facility with the borough of State College. By making the position of superintendent of building and grounds a central one within the administration, Smith hoped to call attention to the necessity of adequately caring for a physical plant that had grown tremendously since the turn of the century and whose maintenance demanded an increasing share of the College's budget. In 1918 the campus counted more than twenty major structures worth a total of $3.5 million and located on some 80 acres of land. (Total holdings amounted to about 1,600 acres, mostly wooded or farm land.) The advent of a more active alumni association was yet another phenomenon that occurred at Penn State and many other land-grant institutions in the early 1900s. While alumni interest was strong at long-established colleges, among land-grant schools, where traditions were not so hallowed and the number of students graduated was comparatively smaller, alumni had remained on the whole a passive lot. An Alumni Association had existed at Penn State since 1870 but had not fulfilled the objectives its founders had set for it, partly because of the nature of Penn State's graduates. They were predominantly technical men, employed by industries throughout the country and liable to frequent changes of residence, thus making coordinated activities among the alumni exceedingly difficult. At Penn State as at most other institutions, the rise of an organized system of intercollegiate athletics did more than anything else to awaken the interest of former students in their alma mater. As previously noted, by 1910 alumni exercised considerable influence in the College's athletic program.

With nurses and patients in the infirmary is Dr. Joseph P. Ritenour.

When alumni representation on the board of trustees went from three to nine members in 1905, it was a further reflection of alumni willingness to assume a more prominent role in shaping the future of the institution. H. Walton Mitchell, the Pittsburgh attorney (and later judge of Allegheny County's Orphans' Court) who had helped General Beaver settle the Great Strike, was elected president of the board soon after Beaver's death in 1914, becoming the first alumnus to hold that post. The College sanctioned the opening of a permanent office for the Alumni Association in Old Main in 1910, the same year that the Association issued its first periodical, the Penn State Alumni Quarterly, edited by its first salaried secretary-treasurer, P. Edwin Thomas. Thomas soon relinquished his job to the ubiquitous Ray Smith, who in 1914 launched a second publication, Penn State Alumni News, to give readers more up-to-date information about campus events. The Quarterly was discontinued in favor of the new journal in 1918. Both periodicals proved to be valuable tools in the Alumni Association's drive to establish more branch chapters. By 1915, eight such organizations were thriving in Pennsylvania, nine in other states, and one in the Panama Canal Zone.

Edwin Sparks seized upon the new vitality of the Alumni Association as a means of alleviating the College's financial plight. In the first issue of the Alumni Quarterly, he told the alumni that in his estimation, the greatest service they could perform would be to work for an increase in the institution's income. What Sparks had in mind was neither a drive to extract donations from former students nor a scheme to bully the legislature into increasing its appropriation, but rather a plan of "education." The alumni's most important goal, he wrote, "is the task not of soliciting or harassing the members of the General Assembly, but of informing them concerning the work of the College and the reasons for its better support."

In September 1916, a low-key fund-raising campaign began, and an "alumni booster committee" was formed to coordinate activities. The committee prepared an informational pamphlet or "booster book" for mailing to all alumni, state political leaders, and public libraries in Pennsylvania and produced two films for general distribution describing student life and the College's academic contributions. Alumni groups were encouraged to call upon legislators personally in their respective districts to discuss with them the work of the College. The booster campaign was a reincarnation on a grand scale of the approach used by George Atherton and Louis Reber. Like Atherton's and Reber's efforts, the campaign of 1916-17 ended with mixed results. Penn State's biennial appropriation exceeded $1.5 million, up nearly $300,000 from its previous allotment, but far short of the $3.5 million the College had requested.

THE COLLEGE AND WORLD WAR I

The booster campaign ended in anticlimax. By 1917 nearly everyone's attention was fixed on events in Europe. The flames of a war that had been consuming the European continent since August 1914 were about to engulf the United States. During the early years of that conflict the question of American neutrality divided the Penn State community no less than it divided the nation. Should the United States remain neutral at all costs, or should it come to the aid of Great Britain and France in their struggle with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire? Not until the fall of 1916-ironically as President Woodrow Wilson was campaigning for reelection on the theme that he had kept the nation out of war-did the first signs appear at the College that America might soon become something other than an interested spectator. The cadet regiment, composed of all physically qualified male freshmen and sophomores (juniors and seniors were no longer required to participate) finally exchanged the blue uniforms that had been a hallmark of Penn State military training since the Civil War for the regulation olive drab apparel of the regular army. Weekly drill periods were lengthened; and in contrast to past indifference, students participated in these exercises with at least occasional seriousness of purpose.

Through the National Defense Act of 1916, Congress authorized the formation of a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) to help supply the leadership the army would need in the event of a sudden involvement in a large scale war. Students enrolling in ROTC units, which were to be established on a voluntary basis at colleges nationwide, would receive instruction in military subjects in addition to their normal academic studies. Upon graduation they would be awarded reserve officers' commissions. Since Penn State already had a military cadre-albeit one limited to freshmen and sophomores and offering no promise of commissions-the College declined to Join in the stampede of institutions that besieged the War Department with requests to set up ROTC programs on their campuses.

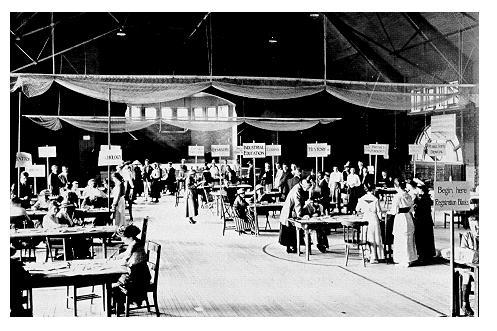

Registration in the Armory, about 1917.

Relations between United States and Germany worsened throughout the winter of 1916-17. On February 3 diplomatic ties were severed. Two days later, 2,300 Penn State male undergraduates voted to send identical telegrams to President Wilson and Governor Martin Brumbaugh advising them "that we tender our services, in whatever capacity they can be used, for preserving the national rights of a country against aggression." The measure was a purely symbolic one, but it did show that student opinion was fast congealing in favor of America's entry into the war. In March the board of trustees seconded the students' gesture by volunteering the use of the College's grounds and buildings to the War Department and to the Pennsylvania National Guard for training purposes. After Congress issued a declaration of war against Germany on April 6, gestures turned to action, as the first wave of students left the College to enlist in the military or to take civilian defense jobs. Unsure how to handle this exodus, President Sparks and his Council of Administration decided to award academic credit for the entire semester and a course grade equivalent to the one earned upon termination of studies to all students who could present proof that they were engaged in war-related employment. By the time June commencement arrived, about 200 undergraduates had Joined the Army or Navy and another 570 were working on farms or in defense industries.

World War I was America's first technological war. Because the nation's colleges and universities could provide on a continuing basis the large numbers of technically trained men demanded by this kind of conflict, these institutions assumed a strategic value that they had not possessed in previous wars. Edwin Sparks joined presidents and representatives from 187 institutions of higher learning in Washington, D.C., in May to discuss how their schools' human and material resources could best be utilized. It was agreed that students should be discouraged from enlisting for military service until they graduated or reached the draft age of twenty-one so that they might take with them into the service as much prior training as possible. This training should incorporate topics that were militarily valuable, and as many students as possible should have the opportunity to enroll. Upon his return to Penn State, Dr. Sparks applied to the War Department for a Reserve Officers' Training Corps unit, which was formed in the fall of 1917 and comprised more than two hundred juniors and seniors.

At the Washington meeting, college and university officials also promised to cooperate fully with the federal government and the quasi-military agencies that had been created to coordinate mobilization for war. The implications of this pledge were not to be realized for many months. In the meantime, Penn State geared up to meet the emergency. The 1917 summer session for teachers began on schedule with a record enrollment of 1,104. Except for compulsory military drills for men and a course in first aid and nursing for women, the session resembled those of past summers.

More defense activity occurred in the School of Agriculture, which added personnel to its county extension staffs to assist in the campaign to increase Pennsylvania's food production. County agents became official representatives of the federal government in overseeing the planting of additional corn, wheat, and other staple crops and proved invaluable in cutting through bureaucratic red tape to help farmers to obtain the extra fertilizer and seed they needed. Agents kept meticulous records of food production and storage as part of a government plan to export as much food as possible to America's I allies without undercutting domestic needs. Home economists, who had been added to the extension staff under the Smith-Lever Act, fanned out across the Commonwealth with information on home canning of surplus foods and planning nutritious meals using substitute foods for those that might not be available because of war-induced shortages.

When the fall semester began, approximately three-fourths of the 1,600 freshmen, sophomores, and Juniors of the previous year returned to the campus, a signal that students were heeding the message to stay in school. A freshman class slightly larger than the one admitted in 1916 put the College's total enrollment at about 1,900, down less than 300 from 1916-17. Soon after the new academic year got under way, the School of Engineering became directly involved in military training through its new course in "storekeeping, accounting, continuous inventory, disbursing, and transportation." Students took it on a voluntary basis in addition to their normal academic load. Hugo Diemer originated the course at the request of the Army Ordnance Department, and it was taught by Assistant Professor of Industrial Engineering J. Orvis Keller.

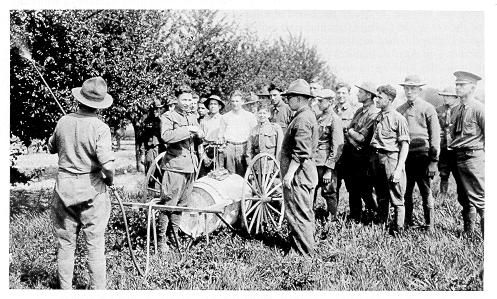

Members of the Boys' Working Reserve learn proper techniques for spraying fruit trees.

The war had not yet caused a significant disruption in the academic routine at Penn State. There were the usual plantings of war gardens and campaigns on behalf of liberty bonds, of course; but in spite of succumbing to such occasional bits of patriotic fervor as renaming sauerkraut "liberty cabbage," students and faculty did not seem to harbor the intense anti-German feelings that prevailed at some other institutions. No serious attempt was made to delete the German language from the curriculum. True, German eventually ceased to be taught for a short time, but it was squeezed out by military subjects added at the direction of the War Department. Nor did any threat materialize to remove German books and periodicals from the shelves of Carnegie Library. To the contrary, the faculty expressed fear that the war would halt the flow of internationally respected technical and scientific writing from Germany, causing irreparable loss to the library's holdings. During the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries many American scholars went to Germany to pursue doctoral studies, for the universities there led the world in the quality of their graduate education and in fact set the pattern after which American schools fashioned their own graduate programs. After the United States entered the war, faculty trained at German institutions were thought to have divided loyalties and became objects of suspicion on many American campuses. Relatively few members of the teaching staff at Penn State held Ph.D.'s from German or any other universities, thus sparing the College the embarrassment of having the patriotism of its faculty called into question.

Neither Penn State's faculty nor its students questioned the wisdom of unconditionally committing their school to the war effort. They viewed their institution's participation in defense work as the logical culmination of the service ideal of land-grant education, Furthermore, instruction in military subjects represented no departure from past practice, having been explicitly called for by the Morrill Act of 1862. On college campuses everywhere there was the feeling that in time of war, the survival of the nation was at stake. If making academic institutions instruments of the federal. government would significantly increase the chances of military victory, then the traditional freedoms and independence of higher education had to be sacrificed for the duration of the crisis.

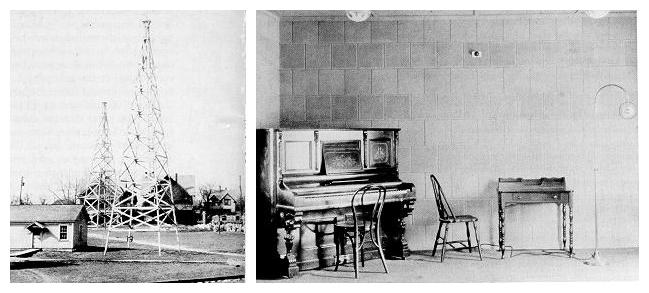

This view was never seriously challenged, even as the College was being transformed into first a trade school and then an armed military camp. In December 1917, Perm State agreed to join about 150 other colleges and vocational schools in providing technical training for large numbers of army enlisted personnel. To make room for the expected influx of soldiers, the College was put on an accelerated schedule for the remainder of the academic year, and commencement exercises were held on April 24, Three weeks before, a vanguard contingent of two hundred men from the Ordnance and Signal Corps had arrived to begin eight weeks of instruction in such subjects as carpentry, sheetmetal working, and radio telegraphy. Additional contingents followed until by midsummer over a thousand men were undergoing training in automobile repair, topographical surveying, and other topics selected by the War Department.

The greatest burden fell on the School of Engineering, which was hard pressed to find enough teachers since it had lost so many of its regular faculty to the army's Engineering Reserve Corps and war industry plants. The School of Agriculture also supervised a vocational training program, although it worked with civilian rather than military students. Soon after the close of the spring semester, the school and the U.S. Department of Labor's Boys Working Reserve cooperated in establishing a Farm Training Camp on the campus, the only camp of its kind in Pennsylvania. Four groups of about 250 youths each were selected from the Working Reserve, a volunteer army of males between ages of 16 and 21, to attend the camp for two-week periods of intensive instruction in the rudiments of farm work. The students were then dispatched to "liberty camps" scattered throughout the state and from there they were assigned as needed to nearby farms in an attempt to relieve the labor shortage that threatened to limit food production.

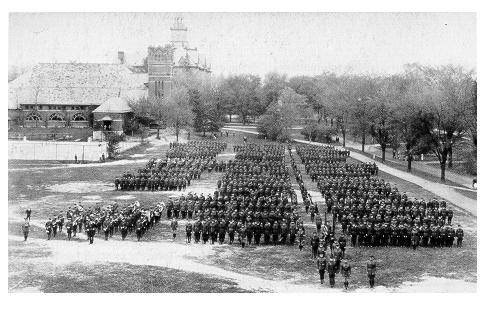

The Student Army Training Corps in formation, 1918.

Before the year was out, nearly every department in the College became involved in some manner in national defense. In February 1918 the War Department created a joint civilian-military Committee on Education and Special Training (CEST), whose principal objectives were to encourage students to acquire as much education as possible before entering military service and to develop a standardized program of defense-related instruction for these students. In the spring of 1918, the CEST formed the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), a unit of which was to be established in September at all colleges and universities and at all professional and technical schools enrolling at least a hundred males over the age of twenty-one. As originally contemplated, enlistment in the SATC was to be voluntary and all SATC students were to receive fifteen hours of military field and classroom instruction every week at government expense. It was hoped that the SATC would give students more tangible evidence that they were helping their country and at the same time give the War Department more control over the kind of training available at institutions of higher education.

The SATC, as originally planned, would have been little more disruptive of the academic routine at Penn State than the Reserve Officer Training Corps, but in August Congress decided to lower the draft age to 18. In the absence of educational deferments, this action left the SATC without a reason to exist and threatened to deplete the ranks of the college population. With the consent of the War Department, the CEST resorted to the drastic measure of making enlistment in the SATC compulsory for all physically qualified male college students. The only legal means by which this could be accomplished was to make each student an army private on active duty. This wholesale conscription in effect nationalized all colleges and universities and enabled the federal government through the CEST to dictate their curriculum. Legally speaking, the executive powers of military commandant Major James Baylies exceeded even those of President Sparks. Required military instruction was increased to thirty hours per week, put under the direction of some thirty officers, and covered such topics as grenade throwing, bayonet practice, and trench construction. Even instruction in the humanities was altered to suit the exigencies of national defense. History, economics, and political science courses all focused, by government fiat, on the background of the European conflict and America's war alms. Study of the French language assumed an importance it had never known before. At Penn State even the library offered its support, as head librarian Erwin Runkle busied himself amassing special collections in military history, and-his personal favorite-" adventure and daring."

SATC cadets on the march near the Armory parade ground.

The CEST put all institutions on a quarterly academic calendar, with the first term beginning October 1. At noon on that day, over 1,600 Penn State undergraduates gathered on Old Main lawn to take the oath of allegiance, sing the national anthem, and listen to the reading of a telegram from President Wilson. Identical ceremonies occurred simultaneously at five hundred college campuses across the nation as over 150,000 students were inducted into the Student Army Training Corps. All members of the SATC were expected to have obtained sufficient training within nine months to enable them to be transferred as needed to military assignments both at home and overseas. Going to college was hardly an option for any youth who wished to avoid service in the armed forces.

The SATC snuffed out the remnants of student social life at Penn State. Undergraduates had to wear uniforms at all times and observe military regulations just as they would at any other military base. To meet the demand for additional living quarters, fraternity houses were converted to barracks, two new barracks were erected on Old Beaver Field, and a mess hall was built adjacent to McAllister Hall. A rigidly prescribed schedule governed daily activities, with students rising promptly at 7:00 A.M., marching to and from classes and meals, and observing a strict 8:30 P.M. curfew. While this routine bore only an approximate resemblance to real military life-surely most troops on active duty did not enjoy the luxury of a seven o'clock reveille-and was well insulated from the horrors of combat, it did make freshman customs seem downright childish by comparison. Among the five hundred undergraduates disqualified from the SATC (that is, female students and males who did not pass the physical exam), green dinks and ribbons disappeared as quickly as the old taboo prohibiting freshmen from walking on the grass. Compulsory attendance at daily and Sunday chapel was also discontinued for the first time in the College's history.

Even before the full weight of the SATC was felt, the war was bringing about changes in extracurricular activities. In their spring 1918 production of "It Pays to Advertise," the Penn State Thespians for the first time included women in the cast. (The women's appearance was a short-lived one; not until 1926 would the Thespians again include a female in their show.) A shortage of qualified players was not so easily solved by the varsity athletic teams, although the 1917-18 schedules were adhered to with few modifications. In the fall of 1918, the CEST restricted intercollegiate play, preferring intramural sports as less costly and time consuming and encompassing a greater proportion of the student population.

The great influenza epidemic which struck the nation that autumn further reduced the football schedule. Many communities fared worse than State College, where six students and six townspeople died from influenza. Strict quarantines had to be instituted in many parts of the Commonwealth. The football team managed to play only four games that year, all in November and all under new head coach Hugo Bezdek. Former coach Dick Harlow had resigned in July to join the army. In August, when the schedule still seemed fairly complete, Bezdek, who had coached football at the Universities of Oregon and Arkansas, was secured as his replacement. As head of the Department of Physical Education, Bezdek was also expected to breathe renewed life into the program of physical conditioning that the College ostensibly required of all students. The army and navy had discovered a dismayingly high number of potential inductees physically unfit for service, prompting Penn State and other schools throughout the country to reexamine the place of physical training in higher education.

Outright militarization of the College had been a long time coming; but once an armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, demobilization occurred swiftly. The Student Army Training Corps was disbanded by mid-December. Nearly 2,200 Penn State students and alumni (excluding those in the SATC) saw military service during the World War I, nearly half of them as commissioned officers, along with 49 members of the faculty. Many months would have to pass before most of the students and teachers who had left the College and were fortunate enough to have survived the war could return. Yet life at Penn State as the pre-war generation knew it would never be quite the same, for the institution had come to the end of another era in its history and was about to enter a vastly different epoch.

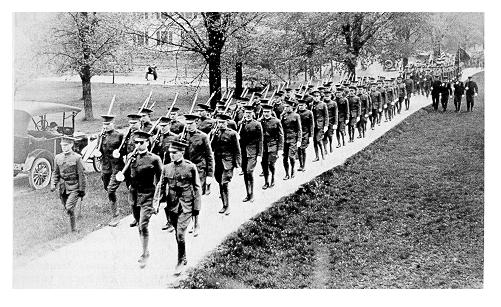

The College experienced this rite of passage literally in a trial by fire. On the evening of November 23, 1918, flames broke out in the rear of the Main Engineering Building, and despite the valiant efforts of Penn State's own student fire brigade and those of the borough's Alpha Fire Company, the structure soon became a roaring inferno. Wind-whipped embers threatened to ignite other buildings until additional firemen from Bellefonte and Tyrone arrived to confine the fire to the Engineering Building and adjacent power plant. The wall of the steam whistle at the power plant first sounded the alarm and then continued throughout the night, a fitting accompaniment to the awful destruction of the architectural capstone of the entire campus. Morning light found the Main Engineering Building a smoking hulk and the College without steam heat and electric power. Classes were cancelled for a few days while utilities were restored, but it was not clear how the College would cope with the loss of one of its most important academic structures, one providing classrooms for hundreds of students and containing thousands of dollars worth of laboratory equipment.

The mental and physical stress arising from the aftermath of the fire proved more than Edwin Sparks could bear, and in February 1919 he suffered a nervous breakdown. Sparks had been extremely active during the war. Besides guiding Penn State through a period of sudden, radical change, he served on numerous state and federal commissions, devoting practically every spare moment to defense work of one kind or another. That he accomplished so much with so little rest and relaxation was due in part to the assistance of Mary Nitzky, who since 1905 had served as presidential secretary and handled many of the administrative chores of the office. In the fall of 1918, Miss Nitzky herself became incapacitated by nervous exhaustion and had to take a temporary leave from her job, forcing Sparks to spend much of his time dealing with petty details. The president was already attending to more routine administrative matters than usual, having assumed many of the responsibilities of Arthur Holmes, who in 1917 had given up his post as Dean of the General Faculty to accept the presidency of Drake University. The burning of the Main Engineering Building simply stretched Sparks' personal stamina too thin. The board of trustees granted him a leave of absence for the remainder of 1919, expecting him to resume his duties by the end of the year.

George Pond, Dean of the School of Natural Science, was named head of a faculty committee charged with carrying on the necessary presidential activities in the interim. After his long period of recuperation, however, Sparks still felt he had not regained his health sufficiently and submitted his resignation. The trustees accepted it with reluctance, although they did prevail upon him to return to his post until the June 1920 commencement. Sparks also agreed to remain at the College as a lecturer in American history, an appointment he held until his death from heart failure in 1924.

JOHN THOMAS AND THE IDEA OF A STATE UNIVERSITY

After it became clear that Sparks would not return, some of the trustees urged Pond to consider the presidency, but he refused, saying that an abler man was needed for the job. Pond perhaps realized that, as an administrator in the style of George Atherton, he would not be well suited to the office. As head of a large bureaucracy increasingly beyond personal control, a college or university president was expected to act more like a coordinator and less like a dictator. He was supposed to possess the talents of a business executive as well as a sensitivity for public relations, and no longer should appear as a father-figure to the student body. Dean Pond had also witnessed how the pressures of the presidency had broken the health of Atherton and Sparks and had no desire to experience the same fate. Ironically, had Pond become Sparks' permanent successor, he would not have made a trip to New England in May 1920 on behalf of the trustees' presidential search committee. While stopping over in New Haven, Connecticut, he contracted pneumonia and died suddenly at the age of 59.

The teaching staff, more than 300 strong (excluding extension personnel), chose this time of uncertainty to press for higher salaries, as post-war inflation steadily diminished the purchasing power of their paychecks. The faculty had made little headway in this matter under Dr. Sparks. Fred Pattee recalled that during the final years of Sparks' regime, inadequate compensation had caused the teaching force to become "an angry, discontented, growling body on the whole," whose motto was "I'll stay here only as long as I have to stay." Pattee complained that the standard response from the administration to any teacher who asked for a raise was, "There are probably fifty men waiting for your job if you don't like it here." In 1920 the trustees surveyed salaries at Penn State and comparable institutions. Dismayed by their findings, they voted to increase compensation by an average of several hundred dollars annually. The trustees' action brought the average income of a Perm State faculty member to about $2,100 per year, still below the competitive norm but a welcome improvement nonetheless.

The amount by which the trustees could raise salaries depended mainly oil the size of the biennial appropriation from the Commonwealth. In an attempt to add credibility to its call for a substantial increase in its appropriation for 1921-23, the College invited representatives from the Pennsylvania Chamber of Commerce to tour the campus to decide for themselves whether the larger sum was justified. A special committee of the Chamber in May 1920 thoroughly scrutinized Penn State's physical plant and interviewed numerous students and faculty. The committee was impressed by the need to expand the institution to meet the mounting economic demands of the Commonwealth. In its subsequent report, the investigative panel declared that "the price of curtailed appropriations to the College in past years has been the growing inadequacy of its facilities and the consequent denial of admission to 3,500 qualified students since 1913. A continuation of these condition will rob the College of the public character derived from its foundation under the Morrill Act and arbitrarily restrict its invaluable service to the Commonwealth in the improvement of agriculture and the mechanic arts."

Main Engineering Building ablaze, November 25, 1918, and its burned-out hulk.

Among the most serious problems facing Penn State, the committee noted, were overcrowded conditions in classrooms and offices, a lack of modern laboratory equipment, and faculty salaries that even with the recent increases were too low to eliminate a costly turnover in the College staff. Over the previous three years inflation had doubled the cost of fuel, building materials, and laboratory apparatus. Without significant increases in its income, the institution would have to turn away at least a thousand qualified students every year for the rest of the decade.

At its annual convention in September 1920, the state Chamber of Commerce accepted the report and adopted a resolution urging the General Assembly to grant the College the entire $6.4 million it had requested for 1921-23. Whether the Chamber or the College seriously believed that the legislature would or could give Penn State everything it asked for is doubtful. Nevertheless, the lawmakers did respond generously, approving an allocation of over $2.6 million, nearly $1 million more than the 1919-21 appropriation.

The Chamber of Commerce committee's report could hardly have painted an attractive picture of the institution for those candidates who aspired to its presidency. Yet at least one of these men, Dr. John Martin Thomas, professed to see a bright future through the gloom; and in January 1921 the board of trustees elected him Penn State's ninth president. Thomas came to Penn State from Middlebury College in Vermont, where he had served as president since 1908. An 1890 graduate of Middlebury, a small liberal arts school, Thomas later studied for the ministry and was pastor of the East Orange, New Jersey, Presbyterian Church at the time of his return to his alma mater. Undaunted by his lack of prior experience in higher education, he set out to put an end to the low enrollments and financial instability that had been plaguing Middlebury for decades. He launched a series of fund drives leading to the erection of five dormitories, a classroom hall, a gymnasium, a chapel, and an infirmary. An unprecedented outpouring of support from alumni and other benefactors enabled Thomas to raise Middlebury's annual income from $400,000 to 1908 to over $1.6 million by 1920. He even convinced the Vermont legislature to make an appropriation to the school. Expansion of the curriculum matched the growth rate of the physical plant and in turn helped to swell the undergraduate population, which rose from 203 to over 600 during his tenure.

For working these near miracles at Middlebury, Thomas gained the reputation in educational circles as a dynamic individual, a man, according to Middlebury's historian, "who could initiate and direct activities, who could sway opinion, never waiting behind the desk for orders to come first from a higher source, a man who could beg, stir, bargain, play emotions, and act quickly when intuition pointed to the moment for action." Behind the stereotyped facade of the mild clergyman, friends and colleagues said, was a personality cast in the same mold as his idol, the charismatic Teddy Roosevelt.

If Thomas were truly a miracle worker, Penn State's trustees reasoned, would he not be the ideal choice to succeed Edwin Sparks? John Thomas loved Middlebury; although leaving it was not easy, he had already prophesied his departure: "If I am ever attracted away from Middlebury," he had confided to a friend in 1918, "it will be by a state institution of unrealized possibilities." In The Pennsylvania State College he saw an institution that fit that description. Aside from its work in engineering and agriculture, the College had long stood in the shadow of other colleges and universities both in Pennsylvania and nationally, and what prominence it did enjoy only reinforced its image as a technical school. Yet by virtue of its charter and its land-grant designation, Thomas believed, it was a state institution and therefore had a broad range of educational responsibilities to the Commonwealth, responsibilities that could be met only when the institution began receiving its fair share of Pennsylvania's tremendous wealth.

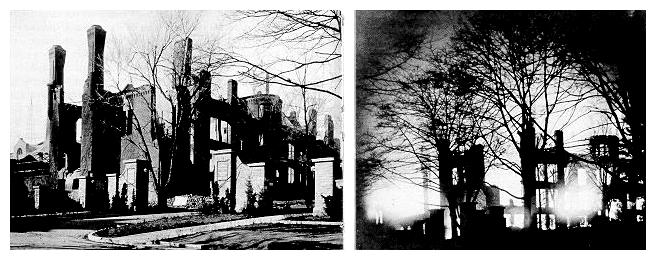

Gathered for President Thomas' inaugural are (from left) Thomas, H. Walton Mitchell, and President Sparks.

Thomas assumed his new duties in April 1921. He lost no time in enunciating the objectives of his administration, unveiling his general plans to a special session of the trustees convened that same month. He informed the board that he expected to undertake a large-scale expansion of the College modeled after the state universities in the Midwest. The first step would be to change the name of the institution to The Pennsylvania State University to reflect what it already was and to symbolize the new era of growth it was about to enter. Since Penn State was to be the state university of Pennsylvania, the Commonwealth must have full ownership and control of the institution just as the Midwestern states exercised complete control over their public universities.

Thomas took a more comprehensive view of Penn State's role in Pennsylvania's educational affairs than had his immediate predecessor. Edwin Sparks had stated in his 1914 report to the trustees that the College's goal "is not to aspire to the much-abused title of university, since the location precludes professional and graduate schools." Sparks wrote in the same report that "it should be the aim of this institution to search every channel of usefulness to the people of Pennsylvania; to benefit in some way every taxpayer; and to make the College the vital center of radiation for information and resulting progress of the Commonwealth." To John Thomas' way of thinking, unless Penn State did acquire the title of University and unless it did develop graduate and professional schools, it was not "searching every channel of usefulness" and was not giving Pennsylvania citizens the full benefit of their tax dollars. He saw Penn State's location as an advantage, not a handicap. The College had the most geographically representative undergraduate population of any institution of higher learning in the Commonwealth, regularly enrolling students from all sixty-seven counties and striking a balance between students from rural and urban areas. The time had come not only for Pennsylvania to begin treating Penn State as the state university, but for the institution itself to begin acting the part.

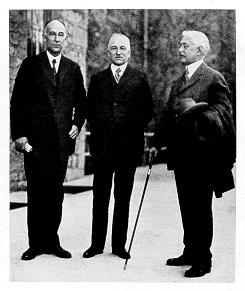

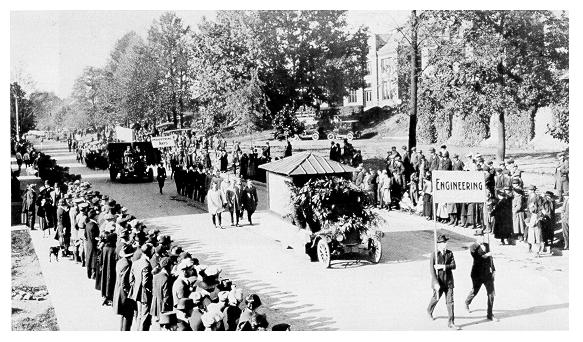

Student parade celebrating the inauguration of President Thomas.

The president's inaugural ceremonies, spread over three days in mid-October, were the most elaborate ever staged at the College and were highlighted by parades, fireworks, and sporting events. The inaugural itself took place on October 14 in Schwab Auditorium where, symbolic of the bond between the Commonwealth and its state college, Thomas had arranged to be introduced by Governor William Sproul and to take the oath of office from Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chief justice Robert Von Moschzisker. His special guests were the presidents of the University of Texas, the University of Illinois, and Ohio State University, all institutions he hoped Penn State would emulate. Also in attendance were representatives from 125 colleges and universities and 44 learned societies.

Thomas' inaugural address was one of the most important speeches ever made by a Penn State president. Instead of wallowing in the platitudes that so often encumber such orations, Thomas spoke explicitly, outlining in precise terms the goals he had pledged the College to work toward under his leadership. He pointed out how the Morrill Act had conferred on the College a broad range of educational obligations that only a university could fulfill. Nine schools that began as land-grant colleges had thus far taken the name university, he said, and several more were preparing to do so. "There is involved no change in ideal or purpose," Thomas assured his listeners, "but only an expansion of education programs and an enlargement of the field of service." The president argued that the university name would facilitate the addition of new technical and professional schools or affiliation with existing schools elsewhere in the Commonwealth. Specifically, he promised to establish a graduate school and a school of education as soon as conditions permitted.

Enlargement of Penn State's curriculum and student body could best be accomplished by having the Commonwealth assume ownership of the university, maintained the president. This action would require only the replacement of some or all trustees hitherto elected by agricultural or industrial societies with trustees elected in a manner guaranteeing a greater voice for the general public. Penn State would thus become the "apex and crown" of Pennsylvania's free public school system. "That does not mean that the state university is to dominate and control the lower schools, still less other institutions of higher learning," Thomas explained. "It means merely that free public education shall not stop with the high school, but go on to college grade. It means that it is the conviction and will of the people of the state that the higher reaches of education . . . shall not be the privilege of the few but the right of all. Not until public education is crowned by a free public university is democracy sincere in declaring that all men are created equal." The president estimated that one student in five seeking higher education in Pennsylvania would enroll in the state university, meaning that Penn State must be able to accommodate 10,000 students within the next few years. Consequently, the institution had to have more classroom buildings and dormitories, a larger library, improved research facilities, and a larger and better paid faculty.

Thomas concluded by asking if Pennsylvania could afford the kind of state university he had outlined. "I answer that no state in the Union can better afford it," he said. Pennsylvania was one of the richest states in the nation by any criteria, he affirmed, but its taxation rate was lower than that of any other state north of the Mason-Dixon line. Yet even a modest tax increase was unnecessary if the legislature would end appropriations to private colleges and universities. "It is wrong principle to grant public funds for private work," the president declared. Pennsylvania did benefit from having an educated citizenry; but the private institutions, not the state, gained the scientific reputation, the alumni loyalty, and other intangible returns of the state's investment. His attitude represented a remarkable reversal of the stand he must have taken while lobbying the Vermont legislature for aid to the sectarian Middlebury. Indeed, the entire agenda was a remarkable one, considering its author had no experience with public or land-grant education.

Mixed reaction greeted Thomas' address. Most of the faculty rejoiced at his call for a period of renewed growth. Frederick W. Pierce, professor of German, spoke for many of his colleagues when he confided to the president shortly after the inaugural that "it has been many years since my heart has been warmed, cheered, and inspired with new hope, such as was inspired in me by your determined stand for our future." The trustees and many alumni also showered Thomas with accolades, variously hailing the plan of action he had dealt out in his address "a great and farsighted program," "a masterpiece," and "long past due." Some members of the board of trustees must have balked at the idea of complete state ownership of the College. However, Thomas surely made known his intentions to the trustees before he had been selected to head the institution. Had the majority of the board members not concurred with him, he would not have been hired. The state Chamber of Commerce, the Pennsylvania State Education Association, and the Pennsylvania Grange also applauded the objectives of the new president.

The U.S. Army Air Service made this photograph of the campus in May 1922 from an altitude of 4,000 feet.

Thomas was particularly gratified that his plan received the endorsement of Dr. Thomas E. Finnegan, state superintendent of public instruction. More than any other individual, Finnegan was responsible for advancing the quality of instruction in the Commonwealth's public school system after World War I, and his cooperation was considered crucial in making Penn State the capstone of that system. Finnegan had originally advocated uniting Penn State, the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Pennsylvania into one grand state-owned and -operated institution (quickly dubbed by wags the "University of Spittsylvania"). He dropped the idea after it received no backing from the schools involved, and had come to view Thomas' plan as the next best alternative.

More than Finnegan's support would be required to win assent from officials of most of Pennsylvania's private colleges and universities. Representatives of these institutions who attended the inauguration were not entirely pleased with what they had heard. The University of Pittsburgh, Temple University, and the University of Pennsylvania, all of which were regular recipients of substantial amounts of state appropriations, could lose this income if Thomas' plans were carried out. Nearly all of the Commonwealth's institutions of higher learning could suffer if the state university, with its free education, siphoned off large numbers of students that normally would have attended the other schools. Many educators believed that Thomas' prediction that only 20 percent of Pennsylvania's college-bound youth would attend Penn State was a gross underestimate. Thomas had already gotten off to a poor start with his counterparts from other institutions within the state by failing to attend the meetings of the Pennsylvania Association of College Presidents. Nevertheless, Thomas was pleased with the overall reaction to his vision of Penn State's future, and he looked ahead with optimism. "I am not innocent enough to imagine that the job will be easy," he confided in a letter to trustee J. Franklin Shields in late October, "but I think we have a right to encouragement that we have made a good start."

Thomas did not expect to depend solely upon the General Assembly for the money his institution would need to triple its size before the end of the decade. As he had done so successfully at Middlebury, he proposed that alumni and other friends of the College share in the responsibility for sustaining its expansion. In June 1921 the board of trustees approved the creation of an Emergency Building Fund campaign with a target of $2 million. The new structures erected with this money were to be used for student welfare and included a varsity hall to replace the deteriorating Track House, a hospital, a home economics building, an addition to Carnegie Library, a student union building, a physical education building, and men's and women's dormitories. More housing for women was especially needed, for the College was turning away as many qualified women as it was accepting due almost entirely to the lack of adequate residential facilities. The Philadelphia firm of Day and Klauder, nationally known specialists in collegiate architecture, was retained to design the new buildings and locate them according to a modified version of the Lowrie plan. Funds were also to be set aside for the restoration of Old Main, which in its old age was beginning to crumble rapidly.

An ambitious goal even for a school experienced in fund raising, $2 million was believed by many persons to be preposterous for Penn State, which had no tradition of extensive alumni giving and which had experienced difficulties simply in raising enough money for a student infirmary. To give themselves time to make adequate preparations for a drive of this magnitude, College officials delayed its start until September 1922. Dr. Thomas himself took the job of director while A. Howry Espenshade, on leave from the Registrar's Office, handled the day-to-day chores as assistant director.

Meanwhile, Thomas and political leaders sympathetic to the College's needs were readying plans to tap still another nonlegislative source of revenue. In his inaugural address, the president had stated that "the trustees and faculty and alumni of this state college have not the power and ability to build [a university]. If we could, it would not be The Pennsylvania State University. This University must be built upon the conviction and by the will of the nine million people of this Commonwealth." Penn State was thus going to take its case directly to the people in the form of a referendum for a bond issue, the proceeds from which would be used to construct classroom and laboratory buildings. The Constitution of 1873 prohibited Pennsylvania's bonded indebtedness from rising above $1 million. Because Thomas wanted an issue of $8 million, an amendment to the constitution was necessary. The amending procedure required the consent of two consecutive sessions of the legislature followed by approval of a majority of the voters. At the same time, Thomas suggested that the College itself issue mortgage bonds in the amount of $2 million, half the appraised value of the institution's property. Following the precedent set in 1866, when the General Assembly authorized Penn State to issue $80,000 in mortgage bonds, the $2 million issue would also need legislative approval but would not have to be put before the electorate, since the College rather than the Commonwealth would secure the bonds and no increase in Pennsylvania's indebtedness would result. Both proposals were put before the lawmakers early in 1923.

For its regular 1923-25 appropriation, Penn State asked the legislature for $4.5 million. At this juncture, John Thomas collided with the hornet's nest of Pennsylvania politics. In the fall of 1922, Gifford Pinchot had been elected governor. A political maverick who prided himself on being free from the influences of the bosses, the Republican Pinchot promised to implement a program of strict economy and erase the $20 million indebtedness the Commonwealth had accumulated since World War I. An appropriation the size Penn State requested was not likely to be favorably received.

In addition, a personal conflict was brewing between President Thomas and the governor, who, although a man of high ideals and unquestioned integrity, had earlier in his career demonstrated an inclination to hold petty grudges and an inability to work effectively with persons who did not share his views. Pinchot won the gubernatorial nomination after a bitter primary struggle against George E. Alter, candidate of the regular Republican organization. Dr. Thomas, also a Republican, tried to remain neutral. Pinchot nonetheless suspected him of favoring Alter and was incensed after College officials permitted Alter to speak on the campus during a campaign swing through Centre County.

John Thomas and Gifford Pinchot

Still another point of friction appeared soon after the new governor took office. Pinchot, one of America's first professional foresters, helped found the U.S. Forest Service while serving under President Theodore Roosevelt and gained national prominence as a pioneer advocate of the conservation of natural resources. He took great interest in Pennsylvania's state forestry school, founded in 1903 at Mont Alto, Franklin County. At one of his first meetings with President Thomas, he brought up the subject of Mont Alto and insisted that Penn State give up its Department of Forestry, saying that Pennsylvania had no need for two forestry schools. The governor made the same demand at the board of trustees meeting on January 23, 1923 (one of only two such meetings he attended during his term of office). The board refused to take any action at first, and President Thomas refused to recommend that Pinchot's demand be met.

Later in the year, amid rumors that the governor would cut the College's appropriation if he did not get his way, the trustees sought to compromise by renaming the forestry curriculum "farm forestry." Even if the issue of forestry had never been raised, a clash between Pinchot and Thomas was probably inevitable. Both men tended to be single-minded, self-righteous zealots who had little tolerance for those who did not Join in their crusades.

Many factors-the need for fiscal austerity, selfish political maneuvering, personal animosity-combined to doom Thomas' grand scheme to build a state university. The legislature responded more liberally than expected, approving both bond issues without a dissenting vote and passing a Penn State appropriation bill of about $3 million. Pinchot believed the amount was too high and used his itemized veto power to reduce it by 25 percent. He likewise substantially reduced appropriations to Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania. He also vetoed the bill allowing the College to use mortgage bonds, contending that the question of whether or not Penn State was a state institution had never been resolved.

Like George Atherton before him, John Thomas claimed that it was. He had earlier obtained opinions from the state attorney general (none other than Pinchot's old nemesis George Alter, attorney general under Governor Sproul) ruling that the College was not obligated to pay certain state taxes and that it had to insure its buildings through the state insurance system rather than with a private carrier. But Pinchot was not convinced. If the College was a state institution, he said in his veto message, then the $2 million bond issue was unconstitutional because of Pennsylvania's one million dollar bonded debt ceiling. If it was not a state institution, then it should mortgage its property without involving the legislature.

The governor's actions stunned Thomas and other Penn State officials. The College was left with an allocation of $2.2 million, nearly $200,000 less than it had gotten in 1921. In those inflationary times, a budget that merely held the status quo was a step backward. Given Pinchot's antipathy toward the land-grant school and his immense popularity with the citizenry, Penn State could not anticipate any significant betterment of its income from the Commonwealth in 1925. Furthermore, Thomas would not consider having the College issue bonds without state authorization, as Pinchot hinted it should, for that would be admitting that Penn State was after all a private institution. The College was therefore more dependent than ever on the successful outcome of the Emergency Building Fund campaign and on the proposed $8 million bond issue by the Commonwealth (which Pinchot had no legal power to veto). To make financial ends meet over the short term, the board of trustees in August 1923 reluctantly raised the student "incidental fee" from $50 to $100.

A UNIVERSITY IN FACT, IF NOT IN NAME

At the time President Thomas was working to increase the College's external financial support, he was using resources already at hand to begin the first phase of the institution's expansion program. His first success came in 1922 with the creation of a graduate school. Nearly 900 students had taken graduate studies at Penn State, although not nearly that many had actually earned advanced degrees. The leaders of the College, either by necessity or preference, had seen graduate work as a secondary function, a view shared by officials at many other land-grant institutions. Graduate studies implied research, but it was often difficult to link research to the kind of applied knowledge that land-grant education was supposed to provide. Only in agriculture, a field where research had obvious implications for improving the public welfare, was there extensive scholarship at the graduate level. Penn State was one of a handful of institutions of any kind to have an engineering experiment station, but the lack of financial support continued to limit its investigations. A mining experiment station authorized by the trustees in 1919 lay almost dormant because money could not be secured to underwrite more than a few insignificant projects.

Advanced degrees in engineering and mining were awarded more in recognition of professional attainments than for academic achievements. The School of Natural Science customarily awarded the Master of Science, ostensibly a degree conferred for academic scholarship; but again, many students, especially those in chemistry, received it after completing several years of nonresident professional work and a brief thesis. Standards for original thesis research were not high in any of the schools, and seminars were few. A shortage of money was not the only hindrance to the development of a first-rate graduate curriculum. Few members of the teaching staff had taken sufficient advanced study themselves to qualify as supervisors of graduate research. Of some 75 senior faculty in 1920-21, barely one-fourth held doctorates. Nearly all the engineering faculty had technical rather than research degrees. Those teachers who were competent to act as mentors to graduate students usually had little time to do so, burdened as they were with heavy undergraduate loads. The best indication of the rank of graduate work in fields other than agriculture at Penn State was the fact that relatively few students came from other institutions. Penn State awarded most of its advanced degrees to students who had also completed their undergraduate studies at the College.

Where Edwin Sparks saw no need to upgrade the institution's graduate component, John Thomas was convinced that a state university must have a strong and diverse line of graduate offerings. He favored the establishment of a graduate school as soon as circumstances permitted, knowing that for a while the school would stand mainly as a symbol that Penn State recognized that higher education did not end with the baccalaureate degree. It would have distinct practical advantages, too, in that it would enable the College to standardize academic requirements for graduate work. It would enable the College to present a united front in the search for more money to support research.

An absence of funds to cover the administrative expenses of the new school did not deter President Thomas. In the spring of 1922, he commenced a personal search for a dean and in May chose Dr. Frank D. Kern, head of the Department of Botany. Kern had not sought the post and, like most of his colleagues, was unaware that Thomas had decided to push for a graduate school so soon. Thus Professor Kern was surprised one day when the president called him into his office and asked him point blank, "If your baby were sick and needed a trained nurse, and you had no money, what would you do?" "I remember without hesitation saying I would arrange for the nurse anyway," Kern later wrote. Upon hearing that answer, Thomas smiled broadly and disclosed his intent to ask the trustees to establish a graduate school by the end of the year. Getting started would be difficult, the president admitted, but he would be pleased if Kern would accept the deanship. Kern said yes, providing he could retain all his responsibilities in the botany department. Thomas agreed, and on June 9 the trustees made the arrangement official as they voted to set up a graduate school early in the forthcoming academic year.

Frank Kern was one of the few faculty members who possessed both administrative experience and an extensive background in research. An alumnus of the University of Iowa, he worked as a researcher with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and at Purdue University's agricultural experiment station before coming to Penn State in 1913 to replace the deceased William Buckhout as head of the Department of Botany. Saddled as he was with teaching assignments and administrative chores, Kern still managed to become one of the most prolific researchers on the entire faculty.

Somehow, Kern found enough money to establish several graduate teaching assistantships carrying a yearly stipend of about $800. In the absence of research grants and fellowships from foundations, private industry, special endowments, and the like, the assistantships comprised the only significant financial award for graduate students, who paid $50 tuition per semester in addition to the usual laboratory and miscellaneous fees. The only other regular source of assistance at the graduate level was the Elliot Fellowship, which was limited to engineering students. (Its sponsor, the Elliot Company, was a Pittsburgh-based manufacturer in the field of electrical engineering.) Doctoral studies were inaugurated in 1924, with the first Ph.D. being awarded to Marsh W. White in the field of physics in 1926. (White was a member of the physics faculty at that time and continued in this capacity until he retired in 1960.) Meanwhile, pressure was brought to bear on the schools of Engineering, Mines, and Natural Science to develop comprehensive programs of resident studies leading to the M.S. degree and to encourage students who wanted advanced degrees to enroll in these rather than seek technical degrees. Enrollment in the Graduate School stood at 155 in 1924-25.

The Graduate School was not the only evidence of President Thomas' commitment to elevate the status of research and graduate studies at the College. In 1924 he selected Dr. Gerald R. Wendt, a nationally renowned research chemist, to be the new dean of the School of Chemistry and Physics, formerly the School of Natural Science. The school's future had been in doubt since Pond's death, and for nearly five years Dean Charles W. Stoddart of the School of Liberal Arts also served as acting dean of Natural Science, while faculty and administration pondered its fate. The problem was that strictly speaking, the title "Natural Science" was inaccurate because many of the natural sciences-geology, mineralogy, botany, and bacteriology, among others-were within the purview of other schools. After much discussion it was decided to forgo any major restructuring and simply change the name of the school to the more appropriate "Chemistry and Physics."

This change paved the way for the appointment of Dean Wendt but did not address a more serious problem. Scientific knowledge was expanding at a rapid rate as the twentieth century gained momentum, yet a lack of money had prevented the old School of Natural Science from keeping pace. It encountered difficulty in hiring faculty well versed in the latest scientific methods and theories, and was unable to acquire modern equipment for use in student laboratories or to enlarge many of those labs to accommodate more students. Sixty students a year were taking freshman chemistry when the Chemistry and Physics Building was opened in 1890. In 1924, 1,200 freshmen were taking essentially the same course crowded into that same building and its small annex. The completion in 1916 of the facility later known as Pond Laboratory prevented a total breakdown but still did not give students the space and equipment they needed to receive adequate instruction. The chemical engineering curriculum (until 1924 the industrial chemistry curriculum) was so substandard that the American Association of Chemical Engineers refused to give it a seal of approval.

Thomas hoped that the incoming dean would change the situation. Gerald Wendt, formerly director of research for the Standard Oil Company of Indiana, received his Ph.D. in chemistry from Harvard and had taught at several institutions known for the high quality of their science curriculums. He pledged to make Penn State one of these institutions, and great advances were expected under his leadership, both at the undergraduate and graduate level.

Wendt was one of the two nationally recognized educators that John Thomas brought to Penn State as deans. The other was Will Grant Chambers, who became dean of the new School of Education. That school, like the Graduate School, owed its birth primarily to the personal initiative of the president. Through the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917, the federal government provided funds to institutions of higher learning for the training of public-school teachers in vocational fields. When Thomas arrived at Penn State, the schools of Agriculture, Engineering, and Mines, and the independent Department of Home Economics all offered teacher training curriculums supported by Smith-Hughes subsidies. The only professional education courses not receiving Smith-Hughes money-and in fact the only education courses not geared to specific subject matter-were carried on in the Department of Education and Psychology, where students could enroll in courses in educational methods, theory, and administration.

In all departments, instruction was geared toward the preparation of secondary-school teachers. The Commonwealth's system of normal schools, established in the mid-nineteenth century, was widely seen as furnishing the most appropriate training for elementary school teachers. Prior to World War I, the number of high schools in Pennsylvania was small and there was little demand for teachers at the secondary level. Around the turn of the century, high schools accounted for only 2 percent of the public school population in the state, ranking Pennsylvania last in this category among all mid-Atlantic and New England states. The College consequently took little interest in developing a comprehensive professional education curriculum beyond the establishment of a Department of Education and Psychology in 1909. Pennsylvania did not begin making progress in public education at all levels until the enactment of the state School Code of 1911, which classified school districts, set minimum teacher standards, established a State Council of Education, and indirectly led to a need for more and better trained teachers. At Penn State the dimensions of this need were not recognized at first. A certain amount of prejudice existed against education curriculums steeped in methodology and theory, the feeling being that a thorough knowledge of the subject field was sufficient qualification for a good teacher. Many faculty and students also had the notion that public-school teaching was a second-rate career, to be pursued only if the student could not find a job in the field in which he or she had earned a degree.

President Thomas saw things differently. He believed that as the capstone of Pennsylvania's public schools, Penn State had a special obligation to improve the quality of teaching at all levels. He did not hesitate to make known his intention of bringing together in a school of education all those students, irrespective of their subject fields, who wished to become elementary or secondary school teachers. Such an arrangement would eliminate the duplication of faculty and facilities that occurred under the exiting system and would result in more effective instruction.

Because the creation of a school of education would have more political repercussions within the College than had the founding of the Graduate School, Thomas had to make a more deliberate attempt to win support from the faculty. He also had to select an individual to head the new school who possessed the necessary experience and leadership abilities. The president believed he had the right man in Will Chambers, a graduate of the normal school at Lock Haven and an educator who had devoted his life to the improvement of teaching training. As a founder (in 1910) and first dean of the University of Pittsburgh's School of Education, he helped put that institution in the forefront of teacher education in the Commonwealth. When a new university administration ordered severe reductions in his school's programs in 1921, Chambers resigned and accepted Dr. Thomas' invitation to join the Penn State faculty, with the implicit understanding that he would be named dean if and when the School of Education were formed.

In the meantime, he held the positions of Director of the Summer Session and head of the Department of Teacher Training Extension, a new department that had been established in response to the General Assembly's passage of the Edmonds Act. Another milestone in the evolution of Pennsylvania's public school system, this act raised the standards for state certification of teachers. Extension instruction of the type being offered by the School of Engineering was needed to help teachers throughout the Commonwealth meet these higher standards as inexpensively and conveniently as possible. Though initially Chambers' department offered instruction only via correspondence, in 1923 it opened the Pittsburgh Teaching Center, consisting of a permanent extension office, several classrooms, and a regular evening faculty. A similar center was opened in Harrisburg two years later. Many teachers who desired to continue their education found it impossible to leave home to attend Penn State's summer session, so in 1924 the Department of Teacher Training Extension began sponsoring branch summer sessions in Altoona and Erie.

Besides supervising extension activities, Chambers worked to have the concept of a school of education accepted. The proposed centralization of all teacher training within a single administrative unit aroused a great deal of antagonism among some of the faculty, who, wrote Chambers in his memoirs, "resented the taking of their students by an upstart competitor; they refused to surrender claims to courses which they had operated for teachers under the old organization, and they freely expressed their disapproval." Some members of the teaching staff also spoke out against awarding baccalaureate degrees to students who completed any of the curriculums in the new school. These curriculums would lack solid foundation in the content fields, the critics charged; therefore, students should earn only certificates similar to those conferred on graduates of the normal schools.

An often bitter series of debates on the merits of a school of education occurred in the newly formed College Senate. With over three hundred members, the General Faculty had grown too large to be effective, and in 1921 the Senate had replaced it as the legislative body on all questions pertaining to academic matters. Composed of department heads, three other elected representatives from each department, and high-ranking administrators, the Senate numbered sixty-three members. The new forum was put to the test during the discussions over a school of education, and in the end Thomas and Chambers won their case. The board of trustees gave its consent in June 1923.

The School was comprised of the formerly independent departments of Teacher Training Extension and Home Economics, along with the departments of Industrial Education, Rural Education, and Education and Psychology, drawn from the schools of Engineering, Agriculture, and Liberal Arts, respectively. Each department was to have charge of its own curriculum, but methodology and other professional education studies were to receive increased attention and were to form a common core of instruction for all students in the school. Although Pennsylvania still did not require a baccalaureate degree for permanent teacher certification, students who completed any of the school's four-year curriculums would earn a bachelor of science or bachelor of arts degree. The creation of the School of Education constituted a major step forward in making available more and better-qualified educators for Pennsylvania's public schools and contributed to the growing professional consciousness of many teachers.

UNFULFILLED EXPECTATIONS

President Thomas' hopes of transforming the College into a great state university continued to be buffeted by financial problems. The results of the Emergency Building Fund campaign were disappointing. The campaign had started vigorously enough, with the institution using every means at its disposal to carry its message to the citizens of the Commonwealth. "Booster clubs" were established in every county, usually under the auspices of local alumni organizations; members were to contact potential donors personally. A mailing list of over 5,000 addresses (excluding those of alumni) was compiled and used as a conduit for a steady stream of letters, pamphlets, and even a weekly tabloid containing information about the work and needs of the College. President Thomas himself kicked off the campaign by leading a "flying squadron" of fifteen Penn State officials in a whirlwind tour of the state, speaking to civic leaders, businessmen, alumni, and anyone else who would listen.