The economic depression that gradually swept over the nation following the stockmarket crash of October 1929 had an especially devastating effect on Pennsylvania, whose prosperity was so dependent upon heavy industry. The value of the state's industrial output fell by over one-half between 1929 and 1932. By March 1933, 37 percent of the state's labor force-nearly 1.4 million persons-were without jobs, and those fortunate enough to be employed often faced declining wages and shortened work weeks. While manufacturing and mining bore the brunt of the depression, Pennsylvania's farmers, too, felt the impact of hard times. Commodity prices tumbled. Corn that sold for an average of 99 cents a bushel in 1929, for example, brought just 43 cents three years later. During that same period, total Pennsylvania farm income dropped from $324 million to $175 million.

Rural central Pennsylvania and The Pennsylvania State College escaped the bread lines and soup kitchens and shantytowns that the Great Depression inflicted upon more densely populated areas. Nevertheless, the depression did have a wide-ranging effect upon the College and made the 1930s as different from the preceding ten years as from the decade that was to follow.

Onset of the Great Depression

Serious economic distress was slow to reach Penn State. As late as September 1931, 4,396 undergraduates were in attendance, a record number. On the other hand, many of these students were beginning to find it financially difficult to remain in school. The costs for an academic year amounted to about $700 for a student with modest tastes-a small sum compared to expenses incurred at some other Pennsylvania institutions, but one that placed an increasing burden on the dwindling resources of many families. Most undergraduates traditionally had helped pay their own way by taking summer Jobs or by finding employment during the school year, but by 1931-32, the number of students seeking part-time work far exceeded the supply of jobs. The College catalog bluntly warned that "opportunities for earning money about the College and in town . . . are few in number and are rarely available to new students. No student should enter college without a sum sufficient to maintain himself at least during his first year." Scholarships and loan funds that year could make available only $4,000.

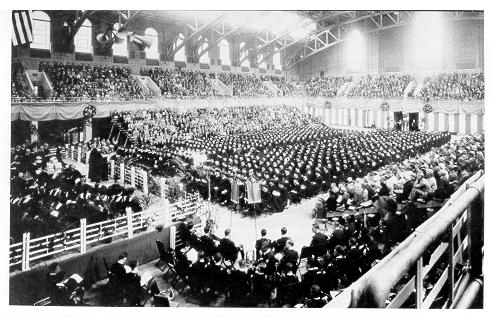

Commencement in Rec Hall, June 1930. This site followed the chapel in the original Old Main and later Schwab Auditorium as the traditional location for graduation exercises.

To ease the plight of the most needy students, as well as the most destitute of families living in Centre and nearby counties, faculty and other College employees established an Unemployment Relief Fund in 1932. Nearly 900 contributors (90 percent of the institution's faculty and staff) raised over $17,000 in a few months. About one-third of the money was deposited in a student loan fund, while the remainder, along with a large amount of surplus clothing, was distributed among some 1,500 families in rural Pennsylvania by Penn State's agricultural extension service. Further augmented by a thousand dollars or so raised through student-organized dances and concerts, the College's scholarship and loan funds aided more students in 1932-33 than ever before, with preference being given to Juniors and seniors. Unfortunately, the number of students needing aid, particularly freshmen and sophomores, still far exceeded available funds.

To compound students' worries, the prospect of finding a job-any job-after graduation grew dimmer with each passing month. College authorities estimated in the spring of 1933 that only one senior in six could expect to secure employment in his or her chosen profession within the next year. Earning a college degree had previously meant taking a giant step toward economic security and higher social status. Now, at the height of the depression, graduates scrambled for almost any kind of job. Chemistry majors drove taxis, political science graduates worked as Janitors, civil engineers sold shoes-if they were lucky. The Collegian aptly portrayed the feelings of many persons in the class of 1933 when it observed that the June commencement "comes like a cold shower after four years of collegiate slumber."

The difficulty of remaining in college and the grim reality of looking for work after graduation eventually reduced the number of students desiring admission to Penn State. During the late 1920s, applications had surpassed openings in the freshman class by a ratio of 3 to 1. By 1933, College administrators were worried that they would no longer be able to attract enough new students to fill freshmen vacancies. Penn State might Join the growing list of institutions that the depression had driven to the financial wall. To avoid that unpleasant fate, a special faculty committee was set up early in 1934 to oversee a recruiting campaign. Postcards were mailed to alumni with the request that they be returned with the names and addresses of high-school students who might wish to attend the College. Alumni were also encouraged to bring prospective freshmen to the campus for one-day visits, and undergraduates were asked to contact the high schools in their hometowns in search of potential candidates for admission. The board of trustees took the unprecedented step of reducing room and board charges by 10-15 percent, depending upon the type of accommodations.

As the fall semester of 1934 got under way, Registrar William S. Hoffman reported 4,945 full-time undergraduates in attendance, a record number. That figure included 1,490 freshmen, the largest incoming class Penn State had yet received. What part the recruiting drive played in boosting enrollment is difficult to assess, however, since several other factors were instrumental in convincing many students and their parents that a college education was still within financial reach.

The first of these factors was assistance from the federal government. Franklin D. Roosevelt had succeeded Herbert Hoover as president early in 1933, and among the many New Deal agencies the Roosevelt regime created was the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. One of the FERA's objectives was to channel millions of dollars in federal money to colleges and universities, which in turn were to allocate these funds to students who otherwise would not be able to continue their education. The philosophical rationale underlying the FERA's support of higher learning paralleled the sentiment upon which the Morrill Land-Grant Act was based, that is, equality of educational opportunity must be maintained in order to maintain political and economic democracy. Unless higher education were available to a large portion of the general population, proponents of federal aid argued, it would revert to its former status as an exclusive province of the economically privileged, and democratic institutions would suffer. The FERA did not aim to put students on the dole, nor did it compel any institution to participate. Cooperating schools were to use FERA subsidies to pay students for performing various chores. Wages averaged about $15 or $20 per month, with most students required to work from 10 to 20 hours weekly. All institutions were to expend one-half of their subsidy on students who were not in school as of January 1934, a stipulation designed to stave off the imminent shrinkage of freshman classes. At Penn State, nearly 20 percent of incoming students received FERA assistance at the beginning of the 1934-35 academic year, and a grand total of approximately 500 undergraduates worked at FERA-sponsored jobs.

The most common tasks, employing over 100 students, pertained to agriculture and encompassed everything from general field labor to laboratory research. Many other students were employed in the laboratories of the School of Chemistry and Physics, where they served as research assistants to the faculty, took inventories, or performed general housekeeping duties. The Alumni Association utilized a dozen FERA workers to compile a new directory of Penn State graduates and former students, containing over 25,000 names and addresses; it was published in 1935 and was the first such public listing to appear in over 15 years. Many coeds found employment in the Department of Home Economics laboratories or in helping to run that department's nursery school. Head librarian Willard P. Lewis made the most unusual use of FERA student labor: He had students comb the obituary sections of selected Pennsylvania newspapers in hope of discovering deceased persons who had left large quantities of books or memorabilia relating to the Commonwealth's history and culture. If the situation seemed promising, Lewis would contact surviving family members and gently hint that the College library would be most grateful for any donations they might wish to make.

Federal assistance to college youths in the form of work programs was to continue at Penn State and at most other institutions for the remainder of the decade. In 1935 the National Youth Administration superseded the FERA in administering these programs, but the objectives and operation stayed essentially unchanged. The two agencies distributed $93 million nationwide by 1940 and assisted over $600,000 students.

Another factor that helped reverse the downward trend in Penn State's enrollment was the establishment of several undergraduate centers or branch campuses in rural areas of the Commonwealth. The College's network of permanent engineering branch schools and teacher-training centers had met with great success during the 1920s, enrolling thousands of students every year. Well before the onset of the Great Depression, prominent citizens from a number of communities had requested the Hetzel administration to expand Penn State's extension activities and set up permanent schools that offered undergraduate courses during daylight hours for full-time students. The institution had the expertise to undertake such a venture, but President Hetzel did not favor it. The junior-college movement was gaining momentum throughout the 1920s, particularly in the western states. Hetzel believed that these two-year institutions were about to blossom in Pennsylvania and other eastern-seaboard states. If Penn State went beyond its present extension activities, it might well stunt the growth of Junior colleges, an outcome that would not be in the best interests of the Commonwealth.

With the coming of the depression, sentiment in many communities in support of the creation of branch campuses by Penn State and other four-year institutions increased. By attending these satellite campuses, students could live at home for a year or two and reduce the expense of a college education. Furthermore, students could more easily divide their time between classes and Jobs if they went to school in their hometowns. And many local civic and business leaders believed that having an existing institution begin a branch campus would be more economical than having the community try to found a Junior college on its own. The University of Pittsburgh had proven the worth of satellite campuses even in prosperous times, having established "branch colleges" at Johnstown in 1927 and Erie in 1928.

In spite of mounting pressure to take some kind of positive action, President Hetzel resolved to move cautiously. Discussing the question of undergraduate centers at the annual meeting of the Pennsylvania State Education Association in December 1931, he stated that "the policy of The Pennsylvania State College relating to this has not yet been determined.... It is one of those matters, it seems to me, regarding which there should be reasonable uniformity of policy among the various educational interests of the state, arrived at free of institutional ambition and solely in the interest of the strongest possible educational program for Pennsylvania." The depression had forestalled any quick spread of Junior colleges across the state, but now Hetzel was concerned that Penn State-sponsored undergraduate branches could undercut enrollment at existing four-year institutions, many of whom were already wrestling with the problem of dwindling admissions.

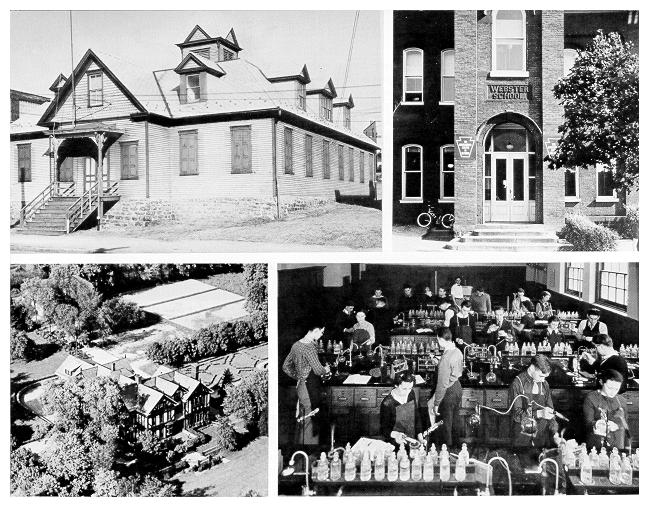

Hetzel realized that something had to be done to alleviate the plight of students who wanted a college education but who, for financial or other reasons, could not leave their homes. Early in 1933 Will Chambers asked the president to consider a plan under which the College would sponsor classes similar to those conducted at the teacher-training centers for students seeking post-secondary education; the classes would be taught by teachers left jobless by the depression. Hetzel liked the idea and secured its approval by the trustees. In September 1933, "freshman centers" opened their doors in Sayre, Towanda, Bradford, and Warren, all towns in the lightly populated northern-tier counties, far from any baccalaureate institutions. Instructors came from the ranks of unemployed or underemployed teachers, and every effort was made to set up a curriculum comparable to what first-year students would find at the State College campus. The Department of Teacher Training Extension had administrative charge of the new centers.

President Hetzel still had misgivings about the wisdom of the experiment. In February 1934, in a talk before the newly organized Penn State chapter of the American Association of University Professors, he stated that he still hoped that Pennsylvania could launch a system of public junior colleges in the near future. Noting the experience of the experimental freshman centers, he declared that it would not be wise for either the College or the Commonwealth to have the land-grant school permanently linked to a group of branch campuses.

However, he was sufficiently impressed with the performance of the experimental centers, as well as sufficiently sensitive to the popularity of the branch campus concept among many Pennsylvania citizens, that he recommend to the trustees that four "undergraduate centers" be organized for 1934-35. Penn State was then beginning to experience its enrollment decline, another factor that may have contributed to Hetzel's willingness to establish these facilities. The new centers differed from their predecessors (three of which were discontinued) in that they were to offer instruction at both the freshman and sophomore levels, and that the teachers were to be employed as full-time instructors with faculty rank. The College selected four communities — Sayre-Towanda, Uniontown, Hazleton, and Pottsville — from the fourteen that had asked to be considered as sites for branch campuses. These communities were chosen only after a careful investigation had shown that they had a definite need for higher education facilities and that other institutions were unwilling to meet this need. President Hetzel had also secured the approval of the Pennsylvania College Presidents' Association before recommending these sites to the trustees.

The curriculum offered at the undergraduate centers consisted of courses in English, history, mathematics, chemistry, foreign languages, and other subjects that comprised first- and second-year studies at the main campus. Ostensibly these centers were to serve other colleges and universities as much as Penn State. "They are intended to prepare students for advanced standing as sophomores and juniors at any institution to which they may later transfer," insisted David B. Pugh, whom Hetzel had appointed central administrative officer for the four centers. "They are not designed to serve as feeders to The Pennsylvania State College." In practice, they did act as feeders almost from the very beginning. The number of students transferring from the centers to schools other than Penn State never came close to the 40 to 50 percent level predicted by Pugh and other officials.

Nearly 150 students enrolled at the centers during their first year of operation. The SayreTowanda campus did not prove successful, and in 1935 it was discontinued in favor of a new center at DuBois. The student body continued to expand as the centers became more widely known. At the start of the 1936-37 school year, 183 freshmen, 83 sophomores, and 155 unclassified part-time students were in attendance. Hetzel was pleased, yet neither he nor the trustees had decided whether the undergraduate centers should remain open for the duration of the depression or should be permanent adjuncts of the College.

In one sense Penn State did have a "branch campus" about whose permanency there was little question. The controversy over the forestry curriculum at the College and at the state school at Mont Alto had remained unsettled through most of the 1920s. Finally, in April 1929, the General Assembly authorized Secretary of the Department of Forests and Waters Charles E. Dorworth to explore the possibility of consolidating Mont Alto with another "state institution" (which everyone realized could only be the Commonwealth's land-grant institution). Dorworth reported that his department would be relieved of a considerable financial outlay if Penn State were to merge with Mont Alto. He also noted that fewer and fewer of Mont Alto's graduates were entering the state forest service, indicating that the school was no longer fulfilling the purpose for which it had been founded. Arrangements were then made by Penn State and Mont Alto administrators to have students in the College's forestry curriculum spend their freshman year at Mont Alto to gain practical experience; they would then acquire more theoretical knowledge and a general education by spending the remaining three years at Penn State. Mont Alto would no longer admit new students. So bitter was the rivalry between the College and Mont Alto that many students at the smaller school elected not to transfer to Penn State and left Pennsylvania to finish their education at forestry schools in other states. They wanted nothing to do with a merger that they claimed was in reality a take-over, no matter how justifiable it might be on economic grounds. The class of 1929-the last group to graduate from Mont Alto-numbered only thirteen students, fewer than half the number that graduated the previous year. The final vestige of the autonomous Mont Alto disappeared in 1937, when the Commonwealth officially deeded the forestry school's property to the College.

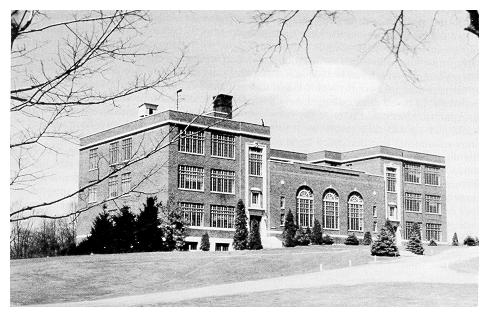

Mont Alto's Science Hall, completed in 1927, two years before the forest academy's merger with Penn State.

The creation of the undergraduate centers and the advent of federal financial assistance eased the hardships faced by thousands of Pennsylvania students and in many cases spelled the difference between obtaining only a high-school diploma and going on for a college degree. And if the depression years remained anxious ones for the great majority of undergraduates, they constituted an era of significant material gain for the College's teaching staff.

Until 1933, when the board of trustees decreed that all salaries must be cut by 10 percent, most faculty members had enjoyed small but regular increases in their annual incomes. Combined with a downward trend in the cost of living after 1929, the teachers were probably better off financially in the first few years of the Great Depression than they had ever been. The pay cut was more than offset by several important advances in fringe benefits, a form of compensation heretofore nonexistent in faculty contracts at the College. In 1932 the trustees voted to implement a group life insurance and permanent disability plan for the instructional staff. Three years later the legislature amended the state employees' retirement statute to make employees of Penn State eligible to participate, an action Ralph Hetzel hailed as "the most vital piece of legislation passed in our interest in the past decade or more." The board of trustees then adopted a compulsory retirement age of 65 for faculty members. The teaching staff received a third important benefit in 1938 when a hospitalization plan was instituted. As with the insurance, disability, and retirement plans, the College and its teachers shared the cost of this program.

Penn State was able to extend these benefits to its faculty largely because it fared well in its biennial state appropriations, the financial stringencies of the depression notwithstanding. The Commonwealth's liberal support of the College was the more remarkable since much of it came during the tenure of Gifford Pinchot, who was elected to a second term as governor in 1930. The rhetoric of Pinchot's second administration resembled that of the first, as the governor spoke out on the virtues of fiscal conservatism and prohibition, and the evils of public utilities and repeal. Perhaps because of the changed economic conditions, Pinchot's actions were often at variance with his words. By the time he left office in 1935, he had outspent the administration of Governor Fisher, whom he had earlier denounced as a spendthrift, by more than 25 percent. Only a few months into his new term, he signed into law a general appropriation of $4 million for Penn State, not cutting so much as a nickel from the amount approved by the General Assembly. "I signed for the simple reason that I considered the expenditure the wisest sort of investment," he said later. The governor did reduce the building appropriation from $1.8 million to $1 million, but the amount was still enough for the College to finance construction of several new structures, including the largest building devoted exclusively to home economics education on any American campus except Cornell University.

Two years later, when economic conditions were at their worst, Pinchot recommended a 10 percent cut in the College's forthcoming appropriation. President Hetzel, knowing a reduction was inevitable and relieved that the governor had settled for one of only 10 percent, called the decreased allocation "Just and fair under the circumstances" and assured Pinchot and the legislature that "the College stands ready to accept its fair share [of reductions] in any necessary and constructive program of public economy." Ultimately Penn State did not even suffer a 10 percent cutback, as the General Assembly voted for and the governor approved an appropriation totaling over $3.7 million for 1933-35, more money than it had received for any biennium prior to 1929.

Curricular Changes and Broadening the Research Base

Not only did the worst aspects of the Great Depression miss Penn State, but what ill effects it did bring to the institution were not prolonged. In fact, the old saw of the Hoover administration about prosperity being just around the corner turned out to be true for the College. Thanks to federal aid, the establishment of undergraduate centers, and aggressive recruiting of freshmen, Penn State easily weathered the enrollment crisis of 1932-34 and went on to set new attendance records almost yearly for the rest of the decade. The undergraduate population surpassed 6,400 by 1939-40, reflecting a 50 percent increase since 1929-30, itself a record year. Yet if higher education remained within the financial reach of most persons who had been able to afford it before the depression, why would any student want to spent four years seeking a college degree, only to Join the same unemployment line as his or her friends, who at best had only graduated from high school?

The newly opened Atherton Hall: (inside) one of more than 200 double-occupancy rooms; (outside) autos line the driveway leading from College Avenue.

The most compelling reason for young men and women to enroll at Penn State and other colleges and universities after 1934 was a negative one: the lack of any practical alternative to the idleness that these youths would face if they remained at home, where even adults could not find work. In many cases college merely postponed this idleness four years; but at least during that time students could nourish the hope that while they attended school, economic activity would pick up and their employment prospects would brighten accordingly. So great was the influx of students that descended upon campuses across America in the middle and late 1930s that the portion of the national population holding baccalaureate degrees rose from 12 percent in 1930 to 18 percent in 1940. Enrollment at Penn State increased at a greater rate than the national average. Because of its low tuition ($100 in 1934 and still termed an incidental fee) and room and board costs, the College lured many students who in more prosperous times would have chosen to attend a more expensive private school. In 1928, Penn State had ranked fortieth among American institutions of higher education in the total number of students enrolled and fourth in Pennsylvania, behind the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Pittsburgh, and Temple University. Ten years later it had climbed to fourteenth nationally and in Pennsylvania stood behind only Penn. With 5,913 full-time students in 1938, however, Penn State had the largest undergraduate body of any school in the Commonwealth.

The number of women admitted to the College more than doubled during the depression. Female students comprised 14 percent of the undergraduate population in 1930 and 20 percent in 1940. The shortage of housing for women, historically one of the most important factors in limiting their numbers at the College, became acute. By 1936, McAllister Hall, the Women's Building, Grange Memorial Dormitory, and the sorority cottages could accommodate fewer than one-half of the 1,000 coeds in residence. Nearly 600 girls lived in boarding houses in State College borough. These quarters were approved by the College officials and subject to their supervision but were regarded (by administrators, at least) as unsatisfactory substitutes for campus dormitories. In January 1937 the trustees approved the issuance of $1.4 million in 3.5 percent bonds to finance construction of a dormitory capable of housing 500 women. A women's athletic building was also to be erected adjacent to the new dormitory. The two structures, subsequently christened Frances Atherton Hall and Mary Beaver White Recreation Hall (in honor of the wife of President Atherton and the sister of General James A. Beaver) were opened in 1938. The College had long needed a building for women's athletics, and Atherton Hall alleviated-but did not eliminate-the housing shortage. Even as the new dormitory was opening its doors for the first time, more than a hundred coeds still had to be assigned off-campus residences.

Most women continued to enroll in home economics, although curriculums in the schools of Liberal Arts and Education were popular, too. Indeed, the rise in the number of female students played a major role in making Liberal Arts, long a stepchild of the College, the institution's largest school by 1933. The School of Education, with three-quarters of its ranks composed of women, ranked second in size. The School of Engineering, having fallen upon hard times, relinquished the position of dominance that it held since 1895 and dropped to third place. It was followed in descending order by the schools of Chemistry and Physics, Agriculture, Physical Education and Athletics, and Mineral Industries (formerly Mines and Metallurgy).

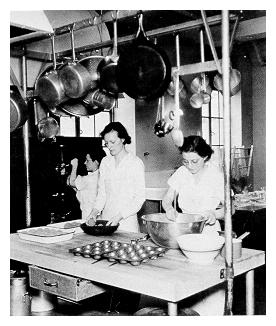

As part of their laboratory work, these students are preparing a meal to be served in the cafeteria of the Home Economics Building.

The liberal arts enjoyed unprecedented favor among students at many land-grant institutions during the 1930s. A materially oriented education, the core of the land-grant philosophy, had proven ineffective in helping the nation avert an economic catastrophe; nor did it seem to offer the kinds of solutions the nation required to cope with the current crisis. Of what use was a practical education if society failed to provide Jobs? Many people supposed that only a liberal education could furnish insights into how and why society, its leaders, and its institutions functioned and what adjustments should be made when they functioned inadequately. The bottom dropped out of the economy, it was argued, because of basic flaws in the American social framework. Students approached the study of the liberal arts, then, with utilitarian ends in mind.

At Penn State, the new popularity of the liberal arts manifested itself in the appearance of a long list of new courses whose titles and content were influenced by the depression. According to official course descriptions, for example, Sociology 5, "Current Social Problems," dealt with "pauperism and public relief systems" and Economics 430, "National Planning," analyzed "defects and pending modifications . . . of our present economic system." The Department of History and Political Science introduced Political Science 422, "Government Regulation of Industrial and Social Life," and History 421, "Recent American History 1900-32." The addition of this history course was noteworthy in a department so traditional that it formally labeled as "A Contemporary History of the United States" a course whose content included nothing more recent than the World War.

Forces unique to Penn State also contributed to the numerical preeminence of the School of Liberal Arts. The School offered baccalaureate work in Journalism-another applied art beginning in 1930, and the new curriculum soon stood second to commerce and finance as the most popular liberal arts degree field. The curriculum in commerce and finance itself continued to attract a steady stream of students, in contrast to a slump in business education at many other institutions. By 1937, the Department of Commerce and Finance enrolled over 320 juniors and seniors, more students than either the schools of Physical Education and Athletics or Mineral Industries enrolled at all four levels. The future for the commerce and finance curriculum seemed bright, and a suggestion was made that the department be detached from the School of Liberal Arts and become the core of a new School of Business Administration. The proposal won solid support from commerce and finance faculty and students, who petitioned President Hetzel and the trustees to consider the action. Penn State, contended advocates of the measure, would be able to expand its academic offerings in business and thus better serve the needs of the Commonwealth; it would also be competitive with Penn, Pitt, and Temple, all of which had separate business schools. Liberal arts dean Charles Stoddart strenuously objected to the plan. His opposition, coupled with President Hetzel's disapproval of the idea on financial grounds, put an end to talk of setting up a new business school in the foreseeable future.

The School of Liberal Arts owed much of its growth to a reorganization in the School of Education under which freshmen and sophomores of both schools took a common curriculum in a new "lower division" in liberal arts. No student was admitted to the School of Education until the beginning of his or her junior year. The Lower Division, approved by the College Senate in 1934, was part of Will Chambers' plan to elevate Education to the level of a professional school and do away with responsibilities for the general education of undergraduates. "There were too many students in our professional education classes," Chambers noted in his memoirs, "who, while intellectually able, had obvious defects of health, personality, moral character, or were without any real interest in the profession of teaching except as a temporary way of sustaining life while completing preparation for another vocation." In a time of few job opportunities, these inferior teachers often prevented better qualified and more dedicated teachers from finding employment, Chambers complained. By admitting undergraduates in their junior year, the School of Education hoped to be able to weed out those undesirable students.

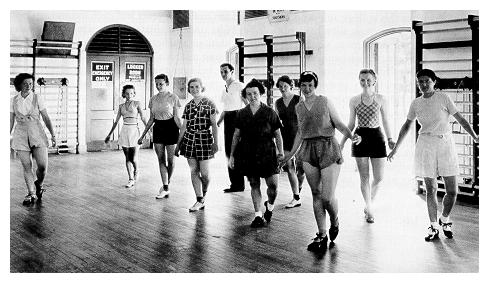

Women's physical education class receives instruction in modern dance, 1936.

The Lower Division worked to the advantage of students in the School of Liberal Arts by giving them more time to decide in what field they wished to earn their degrees. College authorities also assumed (mistakenly, as events showed) that many students would choose to terminate their studies upon completion of work in the Lower Division. The curriculum of the freshman and sophomore years in the School of Liberal Arts was therefore arranged to give students as well-rounded an education as possible, and a certificate was awarded to all Lower Division graduates. In this way, the Lower Division bore a strong resemblance to the general arts and sciences curriculums found in junior colleges-a curious circumstance, in light of President Hetzel's dictum that Penn State should not infringe on the activities of those institutions.

Will Chambers' quest for increased professionalism involved more than undergraduate education. On the eve of the depression, Pennsylvania's fourteen normal schools were being transformed into state teachers' colleges with baccalaureate curriculums. Under the auspices of the Department of Public Instruction, representatives of the state schools and Penn State held a series of conferences in 1929-30 to find means of promoting cooperation and lessening friction between the smaller colleges and the land-grant institution. The teachers' colleges wanted Penn State to accept at full value the credits of any of their students who might enter the School of Education, either to complete their undergraduate education or to work for a graduate degree. Penn State had never accepted in full the credits of normal school students; but since these schools were becoming accredited baccalaureate institutions, Dean Chambers consented to the request. In return, officials of the teachers' colleges agreed that instead of developing graduate programs of their own they would encourage their students to earn advanced degrees at Penn State. This informal understanding, which Chambers cited as "a milestone in the expansion of our graduate work," met with the approval of state education officials.

To meet the needs of the teachers' college graduates and to further professionalize its curriculums, the School of Education developed graduate programs culminating in the M.Ed. and D.Ed. degrees. Chambers' ultimate objective was to have the School of Education function in the manner of medical, dental, and other professional schools. He therefore sought to acquire for the School of Education the exclusive right to set graduate admission and degree requirements. Frank Kern, Dean of the Graduate School, regarded Chambers' plan as an unwise and unnecessary usurpation of the prerogatives of the Graduate School that threatened to undermine the very purposes for which the Graduate School had been founded. With the backing of President Hetzel, Kern successfully blocked any attempt to decentralize authority for graduate education.

If Will Chambers did not reach all of his goals, he still managed to improve the stature of the School of Education. The depression era also witnessed similar revitalization of the work of two other schools, Chemistry and Physics, and Mineral Industries. In each case, the revitalization had at its foundation strong leadership shown by the deans.

In Chemistry and Physics, Dean Gerald Wendt had set out in the years preceding the depression to rescue the school from the malaise that had befallen it. He first issued a series of guidelines designed to improve the quality of instruction. No new faculty were to be hired who did not possess the Ph.D. Present members of the teaching staff were strongly urged to work toward doctoral degrees, preferably at institutions having reputations for excellence in advanced scientific studies. "While this school has many needs, the very first is the strengthening of the faculty," Dean Wendt wrote to a colleague. The implementation of his plan, he said, "will eliminate our present full-time instructors who have often been appointed immediately on graduation from this college and who have stayed ten to fifteen years and even longer, without any more instruction than they have obtained here as undergraduates. This was an expensive custom, and gave us routine, visionless, and unambitious teachers." The school would continue to utilize graduate assistants, but only those holding master's or equivalent degrees were to be given undergraduate teaching assignments. Wendt believed that even complete adherence to his guidelines would only enable Penn State to match criteria prevailing at most other institutions of its size. Much more remained to be accomplished if the College were to rise above the average.

Above-average work required students of above-average competence. Consequently, in the fall of 1925 the School of Chemistry and Physics adopted more stringent rules for academic eligibility, rules that were more rigorous than those laid down by the College' Senate as a minimum for all undergraduates. The process of elimination did not begin in earnest until the sophomore year in order to give new students ample time to adjust to college life. Of the 121 sophomores enrolled in the fall of 1925 in the chemistry, chemical engineering, physics, and pre-medical curriculums, 46 had withdrawn or were dropped by the close of the spring semester in 1926. Exactly one-half of that number were eliminated by the School of Chemistry and Physics' new academic requirements, and presumably these students would have remained under the old rules. The 75 surviving students dwindled to 41 by the end of their junior year, a much higher attrition rate than had previously occurred and proof of Dean Wendt's determination to produce more capable scholars. Wendt also committed himself to upgrading graduate work, which was why he was so anxious to recruit teachers who themselves had solid postbaccalaureate training. He oversaw a reorganization of the graduate curriculum in each department and an increase in the number of graduate courses offered from 20 to 46 by 1928.

A graduate program necessarily depended on a flourishing program of faculty research, but furnishing graduate students with a high-quality education was only one reason to expand the School's research activities. "This state expects from its institutions of university grade not only the men to fill its industries of today," said Wendt, "but also the scientific advances which alone will make the industries of tomorrow possible." In 1926 a Division of Industrial Research was organized within the School to coordinate research resources with the needs of Pennsylvania's industries. Wendt patterned the DIR after a similar unit that had been in operation at the University of Pittsburgh for over a decade, financed by an endowment from the Mellon family. Penn State's Division of Industrial Research, however, would support itself by assessing its clients fees to cover salaries, materials, and overhead. These clients were expected to be small firms and trade associations that could benefit from technical research but could not afford to maintain their own facilities-the same level of industry that the Engineering Experiment Station had been established to serve twenty years earlier.

In 1928, Dean Wendt resigned to accept a post as Director of the Battelle Memorial Institute for scientific and industrial research in Columbus, Ohio. (He later reconsidered and returned to Penn State to serve briefly as an assistant to President Hetzel before embarking on a distinguished career as a science editor and writer.) His successor was Dr. Frank C. Whitmore, a Harvard graduate and former member of the chemistry faculties at Northwestern University and the University of Minnesota. Both men shared the view that research should be given high priority. Under Dean Whitmore, the DIR became engaged in a wide variety of projects that, though small by the standards of many other institutions, constituted a significant advance in scientific research at Penn State. Faculty researchers such as Grover C. Chandlee in chemistry and Wheeler P. Davey in physics conducted investigations sponsored by firms producing everything from Portland cement and textile dyes to baked goods and glass containers. Davey was easily the most prolific investigator among faculty members associated with the Division of Industrial Research. Wendt had convinced him to leave an influential post at the General Electric Company's research laboratories to take on the challenge of invigorating Penn State's program of scientific research. At the request of Dean Whitmore, Davey in 1932 was named the School of Chemistry and Physics' first "research professor," a position that freed him from the responsibilities of elementary instruction and gave him more time to devote to his interest in x-rays and crystal structures. He led the way in developing such esoteric but fundamental techniques as utilizing x-ray diffraction by crystals to identify unknown solid materials and using Geiger counters to measure the intensity of x-rays.

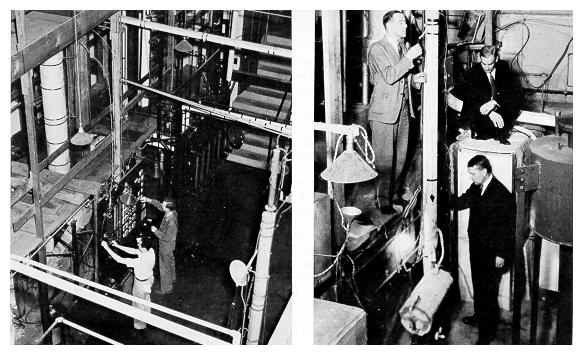

The Petroleum Refining Laboratory's barrel-a-day solvent plant, used to develop improved lubricating oils. At the foot of the heavy-water column are Donald Cryder (left), Merrill Fenske (right), and Harold Urey (below).

The most extensive research in the School of Chemistry and Physics was done not by the staff of the Division of Industrial Research but by personnel of the Petroleum Refining Laboratory, newly established through the support of the Pennsylvania Grade Crude Oil Association. Pennsylvania grade crude oil possessed superior characteristics as a lubricant, yet its chemical it was not well suited for use in the higher compression engines that were used in the newer automobiles. Under the direction of Merrill L. Fenske, a young research chemist whom Whitmore had brought from MIT to head the laboratory, a series of chemical analyses of the composition of Pennsylvania petroleum was carried out with the aim of improving the gasoline refined from it. In 1929, as the PRL was getting started, the state legislature allocated $50,000 to support these investigations. Fenske soon expanded his work to include finding ways to make the entire refining process of Pennsylvania crude more efficient.

When the new campus power plant was constructed in 1930, the PRL moved from Pond Laboratory to the old plant, where more space was available. Among the many projects it undertook in its new quarters was one to develop a process of chemical identification of Pennsylvania petroleum products. The Penn Grade Association had long complained that dealers nationwide falsely represented their lubricants as originating in Pennsylvania. Whenever the Association took legal action against the dealers, the result was unsatisfactory since it was virtually impossible to prove in court that the product in question did come from other than a Pennsylvania field. By perfecting an identification process, the PRL averted a potential loss of millions of dollars for the Pennsylvania Grade Crude Oil Association and the Commonwealth's economy.

Another potentially significant research project in the School of Chemistry and Physics related to heavy water, or deuterium. This substance, discovered in the early 1930s by Columbia University's Harold Urey (an achievement for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1934), was used in fundamental atomic research. The problem was that heavy water was extremely expensive to manufacture because of the need for a tremendous amount of electricity. Commercial production centered in Norway, where numerous hydroelectric plants produced cheap power. Under the leadership of Professor of Chemical Engineering Donald Cryder, Penn State became one of several American institutions searching for a more economical method that could lead to domestic production. Cryder's method utilized a distillation process and relied on techniques pioneered by Fenske in the Petroleum Refining Laboratory. Interested in the process, Urey arranged with the Ohio Chemical and Manufacturing Company,,,, a firm hoping to begin commercial production of heavy water, to finance Cryder's work. Several hundred pounds of deuterium were produced in 1937 and were subsequently turned over it) Professor Urey, who went on to become, a key figure in the nation's atomic research program during World War II. In the end, Penn State's process did not appear to be commercially feasible, and no additional deuterium in substantial quantities was forthcoming.

The School of Mineral Industries' rebirth paralleled that of Chemistry and Physics. The school had never lived up to the potential that Marshman Wadsworth hid envisioned for it when he reestablished it in 1907. Its physical plant was decrepit, consisting of the original wood-frame Mechanic Arts Building, to which had been appended several makeshift wings. Its handful of teachers were barely able to keep up with the demands of undergraduate instruction, and research, graduate studies, and extension were virtually nonexistent, The quality of the student body left something to be desired as well, as might be expected from a policy of accepting nearly every high-school graduate who applied for admission. Common opinion among the College's faculty and students held that the mining school had a large portion of students who could not make the grade academically in the School of Engineering and had to be content with taking a curriculum whose scholarly demands were allegedly less rigorous. Dean of the School of Engineering Robert Sackett leaned heavily on this argument during his frequent attempts to have the College administration disband the school and divide its work between engineering and chemistry and physics.

Rather than accede to Sackett's suggestion, President Hetzel chose to find a person capable of giving the school the kind of leadership it needed to remedy its own problems. In 1928 he selected Edward Steidle as its new dean. A 1911 graduate of Penn State, Steidle came to the College from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where he had reorganized the mining engineering curriculum, initiated its first research program, and succeeded in getting assistance for mining education from private industry. One of Steidle's first acts was to have the name of the school changed from Mineral and Metallurgy to Mineral Industries in order to symbolize the expected diversification beyond the field of coal mining. In 1930, a new brick and, limestone Mineral Industries Building replaced the old mining complex. A year later, Steidle activated the Mineral Industries Experiment Station using funds provided by the Central Pennsylvania Coal Producers Association (a bituminous coal group) tjjd the Anthracite Institute. Like the Division of Industrial Research, it represented art important first step, even though the scope of the research was hunted at first and the station employed no full-time staff. Much of the work the station performed for the bituminous coal industry was related to mine safety, while the Anthracite Institute wanted researchers to find non-fuel uses for its product. Anthracite output hid been declining for a decade, and the industry was looking for new markets to reverse this trend. In 1935 the station entered into a cooperative research program with the Commonwealth, whereby the General Assembly agreed to match research contributions from the private sector up to a total of $50,000 per biennium. Most of these funds were also used to support various aspects of coal research.

Steidle was eager to affiliate the School of Mineral Industries with activities other than coal mining. He was instrumental in obtaining a share of the $50,000 appropriation the School of Chemistry and Physics had received for petroleum research in 1929 and used it to sponsor an investigation of ways to decrease production costs and increase yields of Pennsylvania oil wells. Several years later, extension classes in petroleum mid natural gas engineering were begun fit Bradford, Oil City, Washington, and a half-dozen other communities in western Pennsylvania. So successful was Dean Steidle's campaign to breathe new life into miner-it industries education that in 1939 the General Assembly amended Penn State's charter to provide for a fourth ex officio member of the board of trustees: the Commonwealth's Secretary of Mines.

As Steidle, Whitmore, Chambers, and some of their colleagues discovered, the lean years of the early 1930s offered an excellent opportunity to institute change. Forced economy gave the entire College a chance to remove some of the academic bric-a-brac that had accumulated over previous decades and to adjust the curriculum to changing student interests and needs. President Hetzel in 1931 appointed a committee of faculty and administrators to survey the courses of each of the College's seven schools and make recommendations that would end duplicate instruction and channel the institution's human and material resources into areas where they were most needed. The findings of this committee eventually led to the elimination of nine baccalaureate curriculums and over seventy courses.

Hetzel also instigated changes that streamlined the operation of senior administrative offices. In 1934 he named J. Orvis Keller, formerly head of the engineering extension department, to the post of Assistant to the President in Charge of Extension, where he was to oversee a new Central Extension Office that exercised administrative authority over all the College's extension activities except agriculture. Hetzel thus brought to fruition an idea that had long been discussed and had first been attempted by John Thomas. The centralization of extension services preserved the autonomy of the extramural programs of the various schools, which continued to have jurisdiction over course content, selection of instructors, and similar matters. Keller's office handled most of the administrative work involved in securing sponsoring organizations, selecting class sites, and coordinating the work among the schools. It also took on much of the responsibility for publicizing the College's extension arm and for operating the undergraduate centers.

The schools of Engineering and Education had the largest extension programs (along with Agriculture), while that of Mineral Industries was just getting under way. The schools of Chemistry and Physics and Liberal Arts had done little in the way of off-campus instruction. Lack of initiative was partly to blame, but so was the difficulty of demonstrating to the public any relation between the humanities or basic sciences and measurable material gains. When they approved of the creation of the Central Extension Office, however, the trustees also consented to Hetzel's suggestion that a Division of Arts and Sciences Extension be set up to give some impetus to off-campus work in Chemistry and Physics and Liberal Arts. Soon a few correspondence courses were being offered, mainly in business and mathematics, and community classes in a variety of cultural self-improvement subjects were organized.

The president continued to centralize administrative authority in 1935 when he appointed Adrian 0. Morse, a faculty colleague of Hetzel's at the University of New Hampshire and since 1929 his executive secretary, to the post of Assistant to the President in Charge of Resident Instruction. In this capacity, Morse became Penn State's chief academic officer and had the duty of working closely with the deans and the College Senate in all matters pertaining to undergraduate and graduate education. Samuel K. Hostetter, the College's purchasing agent and manager of dormitories and dining commons, was elevated to the rank of Assistant to the President in Charge of Business and Finance. He assumed all the duties heretofore performed by the controller (a post vacated by the retirement of Ray H. Smith) and a number of lesser business and fiscal staff members. In practical terms, Keller, Morse, and Hostetter all assumed some of the authority previously exercised by President Hetzel and were in essence vice-presidents, a title they would have received at most other colleges and universities. Hetzel avoided this designation, however, perhaps wishing to avert even a mild repetition of the Welsh affair of 1907-10 by making plain to everyone that the ultimate authority still resided in the office of the president.

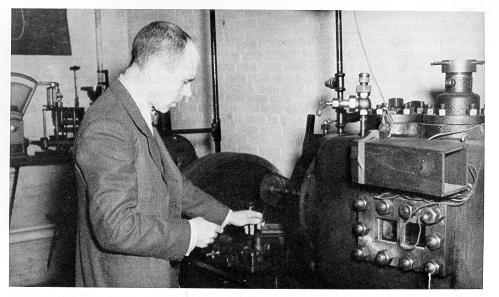

Paul Schweitzer with equipment used in diesel engine fuel oil spray research.

The trustees also created the office of Assistant to the President in Charge of Research, although Hetzel did not immediately appoint someone to the post (and ultimately never did). Like John Thomas, Ralph Hetzel insisted that research in all academic areas was a legitimate and indeed an obligatory function of a land-grant institution. In anticipation of a period of pronounced growth in institutional research, the president in 1930 established a Council on Research, composed of representatives from each major division of the College, to formulate a policy for the kinds of research Penn State should undertake. Hetzel feared that without the Council's oversight, some departments or schools might become too heavily dependent on the private sector to supply the funds and set the goals for research. He viewed the gain in research by the schools of Chemistry and Physics, Mineral Industries, and Engineering with mixed feelings, since most of the sponsoring money came from industry. "In the absence of public funds, it is natural that these schools should accept grants from industrial sources," Hetzel wrote. "The danger is that . . . applied research in cooperation with industries may overshadow and stifle institutional research of a more fundamental nature. The question is not whether such investigations should be eliminated, but how far we can go in this line of work without prejudicing the instructional and research program of the institution that is supported by public funds and unrestricted by contract." The president warned that already the College was "inviting embarrassment in its public relations" by emphasizing its public character on the one hand and acting as an industrial research laboratory on the other.

His concern over this dilemma eventually led to the creation in 1940 of the Central Fund for Research. Begun with a $3,500 allotment from the College's general fund, the Fund for Research was to be used to support research in the social sciences and the basic natural sciences, areas that were not attractive to corporate sponsors. Also at Hetzel's request, the Council on Research adopted a policy stating that private, externally funded investigations should be a "minor feature" of each school's research activity. No school was to conduct any privately sponsored research that did not promise to yield results of public value. The College also established the Pennsylvania Research Corporation to hold patents on scientific processes and inventions and develop their commercial uses, and to act as an additional aid in promoting research for the public good.

The guidelines promulgated by the Council on Research probably made the deans and other faculty members a bit more cautious in accepting industrial research contracts, but they do not seem to have significantly retarded the growth of nonagricultural research generally. The real obstacles to expanding research lay elsewhere. Lack of money, public or private, was one handicap. Another was the faculty's undergraduate teaching load, which was so heavy in most cases that it left little time for research. But even if they did have the time, many members of the teaching staff lacked the competence to engage in significant research, for they did not have the advanced training that was a prerequisite for such work. Of the 134 professors on the graduate faculty in 1935-36, only 65 had earned Ph.D.'s or equivalent degrees. A doctoral degree by itself did not qualify one to conduct research, nor did the lack of a doctorate automatically mean a faculty member was incompetent to supervise graduate students. Yet seen from a faculty-wide perspective, the presence or absence of doctoral training was a fair measure of the academic background of the teaching staff and revealed a definite weakness at Penn State with respect to the faculty's capacity to oversee graduate work and sophisticated research. Furthermore, a sizable portion of the faculty were just not interested in doing research. A tenure system, with its stipulation that faculty must perform research in order to obtain a permanent appointment, did not exist. Having for years placed their highest priority on the instruction of undergraduates, many teachers took the attitude that research should be left for the staffs at the experiment stations.

Cabbage—possibly the award-winning Penn State Ballhead variety—dominates this view of a portion of the College farm.

This view was especially dominant in the School of Liberal Arts. In spite of its remarkable growth, this school contained a large proportion of faculty who were imbued with the old "service" mentality, which held that their most important goal was to teach a smattering of the humanities to students in the technical schools. "In research the work is wholly limited to individual activity," Dean Charles Stoddard had written in 1928. "There is no definitely assigned research and no member of the staff is expected to engage in research as part of his duties." This condition prevailed in the School of Liberal Arts throughout the 1930s. Lack of time and encouragement did not totally prevent important work from being done outside the classroom. Professor of History Wayland F. Dunaway, for example, helped to found the Pennsylvania Historical Association, a scholarly organization dedicated to the study of the Commonwealth's past, in 1933. A few years later he wrote the first college-level textbook on Pennsylvania history, a work of such high caliber that it was widely used in classrooms for thirty years. But activities such as Dunaway's were the exception, not the rule.

Because of its very nature, liberal arts research did not have strong, direct contacts with government and industry that could lead to sustained financial support. Only the Institute of Local Government carried on anything resembling ongoing, organized research. Authorized by the trustees in 1936, the Institute-the first of its kind in Pennsylvania-was composed mainly of political science faculty. They acted as consultants for municipalities on topics ranging from public utilities management to governmental reorganization. Through the Institute, graduate students had opportunities to gain practical experience in public administration.

A casual attitude toward research existed to some extent in all seven of the College's schools and had a detrimental effect on graduate studies. Post-baccalaureate education could hardly thrive in an atmosphere of indifference. Heavy teaching loads and lack of money clearly were not the only reasons that in 1938, when it ranked fourteenth nationally in the number of undergraduates enrolled, Penn State held the thirty-eighth position in the size of its graduate student body.

Nevertheless, given the hardships of the depression, Penn State made substantial progress in building a research base. The work of the schools of Chemistry and Physics and Mineral Industries has already been noted. In the School of Engineering, the staff at the experiment station continued their long-standing efforts to develop more efficient insulation materials for homes, commercial establishments, and even railway cars. By 1930, a second major field of investigation rivaled heat transfer in attracting the attention of professional engineers. Paul Schweitzer, a young Hungarian immigrant, began conducting research in the relatively unexplored area of diesel engineering soon after joining the experiment station's staff in 1923. He was interested in perfecting the spray of fuel oil into combustion chambers as a way of increasing the efficiency of diesel engines. He and fellow researcher Kahlman J. DeJuhasz won international acclaim for their work, and until World War II, the diesel laboratory-which shared quarters in the old power plant with the Petroleum Refining Laboratory-was the most elaborate facility of its kind in the United States. Attesting to the reputation of the diesel lab is the fact that the U.S. Navy in 1929 selected Penn State as one of only two institutions to participate in a master's degree program designed to teach naval officers the intricacies of diesel engineering.

Organized research in the School of Education was in its formative stage in the 1930s. In 1927, Dean Chambers added Dr. Charles C. Peters to the staff of the Department of Education and Psychology as Director of Research. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Peters specialized in educational statistics and wrote a pioneering textbook in that field. He assisted graduate students in the School of Education in the statistical research needed for their theses. In 1931, Dr. Robert G. Bernreuter joined the school's faculty, having just finished graduate studies in educational psychology at Stanford University. He established the Psycho-Educational Clinic as a training laboratory for graduate students in clinical psychology. Bernreuter's "personality inventory," completed the year he arrived at the College, broke new ground in the field of psychological testing and became the standard by which other personality tests were measured.

In the number of faculty engaged in research, the amount of money spent on research, and the diversity of the research topic, Agriculture continued to lead all the schools of the College. Only the School of Agriculture enjoyed the luxury of receiving regular allotments of public funds to underwrite the costs of research. In 1925, in the midst of the agricultural depression,

Congress had passed the Purnell Act, which gave agricultural experiment stations incremental payments that totaled $60,000 annually after five years. This sum was twice the size of the amount Penn State was receiving through the Hatch and Adams acts combined. The Pennsylvania legislature was also beginning to provide liberal support for agricultural research. At the outset of the depression, the Commonwealth ranked behind only New York and a half-dozen midwestern states in annual appropriations for research in agriculture.

Illustrative of the value of agricultural research was a project supervised by agronomy professor C. F. Noll that led to the introduction of a new variety of wheat, "Pennsylvania 44," specifically adapted to growing conditions commonly found in Pennsylvania. It gave farmers the ability to increase yields by as much as five bushels per acre. In times of low prices for wheat and other farm commodities, the object was to maintain the same production level but use less land and thus reduce expenses. Similar improvements were made with new varieties of oats, tomatoes, and cabbage. In the poultry husbandry department, new breeds of chickens were developed that reduced first-year mortality on Pennsylvania's poultry farms from 50 percent in 1928 to less than 20 percent in 1938. Andrew Borland in dairy husbandry, Ernest L. Nixon in potato culture, and E. B. Forbes in animal nutrition were only a few of the many faculty who made important contributions to the improvements of Pennsylvania agriculture.

Research in home economics received an important stimulus in 1941 with the formation of the Ellen H. Richards Institute through a cooperative agreement between the schools of Agriculture and Chemistry and Physics. (Ellen Richards [1842-1911], the first woman to earn a degree in chemistry from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, devoted her career to applying chemistry to improve living conditions in the home.) Under the direction of Pauline Berry Mack, a member of Penn State's chemistry faculty since 1919, the institute conducted studies on such topics as the nutritional value of school lunches, the efficiency of commercial laundering methods, and the durability of textile fabrics and dyes. The most highly publicized accomplishment of Professor Mack and her colleagues was the perfection of an x-ray process that determined the mineral content of bones, providing a means of diagnosing nutritional deficiencies. Most of the research projects at the Institute were sponsored by business firms and trade associations.

More Improvements to the Physical Plant

The most tangible sign of Penn State's depression-era growth came in the form of nearly a dozen new buildings that were erected on the campus late in the decade. The ever-larger student body made a corresponding increase in the size of the physical plant mandatory, but the financial conditions of those years cast an air of uncertainty over the question of where the College would find the money for new construction. It could borrow funds, as it did in the case of the new women's dormitory and recreation building. However, President Hetzel and the trustees concurred in the necessity of preserving the institution's fiscal integrity and were wary of borrowing any more money.

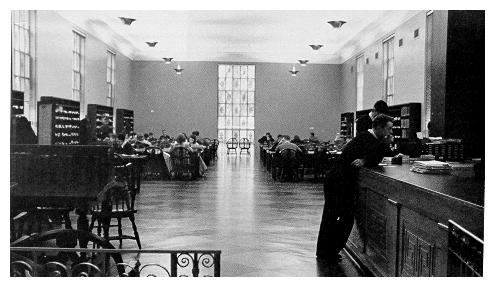

The second floor of the new Library included the reference desk and was also a favorite place to study.

An alternative source of funds appeared in 1935 as George H. Earle succeeded Gifford Pinchot as governor. The first Democrat to serve in that office since Robert E. Pattison, Earle likened himself to the popular Franklin Roosevelt and promised to bring a "Little New Deal" to Pennsylvania. He advocated a host of social welfare and public service programs, among them a series of major construction projects for state hospitals, prisons, colleges, and other institutions. These public works cost a great deal of money-money which the Commonwealth did not have and which it could not borrow because of the constitutional limit on indebtedness. To circumvent this restriction, Governor Earle proposed to set up a quasi-private corporation, the General State Authority, to act in the Commonwealth's behalf The GSA would first issue bonds to finance construction of new buildings and other public works as well as to purchase the land upon which they were built. Then it would lease the property back to the Commonwealth and use the income front these leases to repay its bonds. The GSA would also give Pennsylvania the opportunity to obtain federal aid, primarily through the Public Works Administration, an agency that had been established several years earlier to help state and local governments and private industry finance large construction projects.

The Earle administration set up the GSA early in 1935, but Pennsylvania's Supreme Court promptly declared it unconstitutional. Political and public pressure wits brought to bear on the court, and in January 1937 the legislature re-established the authority. Attorney General Charles Margiotti then petitioned the justices for a rehearing on its legality. This time the court gave its approval. The GSA came to life at once, announcing a statewide building program to be paid for by a $20-million grant from the Public Works Administration and a $45-million bond issue. So that there would be no question that Penn State would be among the institutions to benefit from this Program, the General Assembly had inserted an amendment in the act setting up the GSA that specifically named Penn State as art eligible recipient.

The Supreme Court's sudden change of heart and the rapidity with which the GSA went into action took Penn State officials by surprise, President Reuel had- earlier estimated that the College needed 910 million worth of additions to its physical plant, but only a very general building scheme had been drawn up. Now Governor Earle was promising $6.7 million from the GSA if Penn State could expeditiously submit a list of detailed requirements. After some hurried conferences with faculty and trustees, Hazel sent to Harrisburg a proposal for over a dozen new structures.

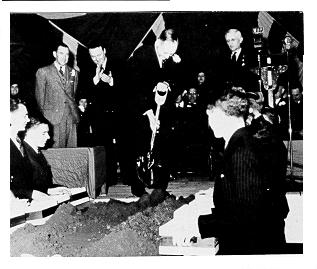

President Hetzel turns a symbolic shovel of earth at building dedication ceremonies, February 26, 1938. To his immediate right is Governor George Earle; to his left is Col. Augustine Janeway, head of the General State Authority.

Included on the list was a new library. The College had never possessed a library adequate for its needs, either in shelf and study space or in the size of its holdings. Because of the heavy emphasis on technical education at the undergraduate level, and the existence of small libraries maintained by individual schools and departments, Penn State was able to live with its handicap until the rapid growth of the 1930s. "Inadequate for the books it now contains, too small for the comfort of the many students who in ever-growing numbers seek its advantages," editorialized the Collegian in November 1932, "the library presents a doleful spectacle to visitors who have wandered through the libraries of institutions which we are accustomed to speak of in the same breath as Penn State." The limitations of Carnegie Library particularly hampered the College's attempt to promote faculty research and expand graduate studies in the School of Liberal Arts, whose faculty and students depended upon the library in the same way scientists and engineers relied on the laboratory. During the early years of the depression, the Hetzel administration cut back the library's budget as part of an overall effort to reduce the institution's operating expenses. Head librarian Willard Lewis had to content himself with making improvements that did not require much money or additional space. After 1935, for example, all newly hired members of the professional staff had to possess a baccalaureate degree plus one year of specialized training in library science. Lewis was delighted when President Hetzel informed him that $1 million in GSA funds was targeted for a new library building, although he had previously told the president that the cost of a truly first-rate structure would approach $2 million.

Pressed by construction needs and political considerations at other state institutions, the General State Authority granted Penn State $5 million in building funds instead of the $6.7 million that Governor Earle had mentioned earlier. College officials had no choice but to reduce the scope of the building program, eliminating some of the proposed buildings and scaling down others. The allocation for a new library was cut by over half. The specific factors weighing in this decision remain unclear. Librarian Lewis later would recall only that "demands on the part of other units" of the College necessitated the reduction. In any event, a substantial amount of stack and office space was dropped from the original blueprints to give a building capable of housing barely 300,000 volumes-only a few thousand more than Carnegie Library then contained.

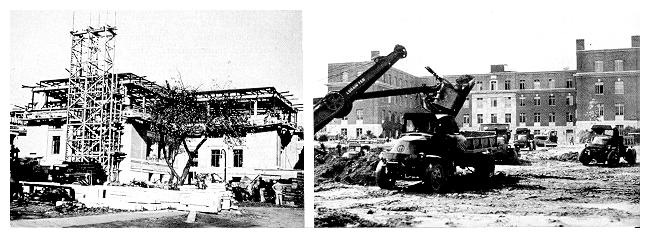

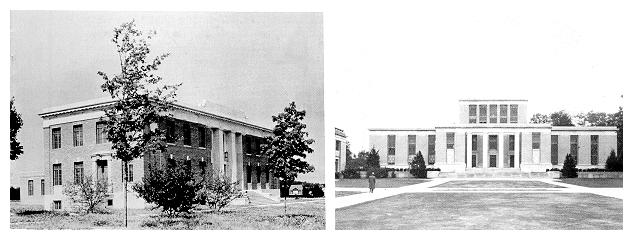

New construction in the late 1930s: (left) the central unit of the Liberal Arts (Sparks) Building; (right) excavation for the Electrical Engineering Building.

These severe cutbacks in the plans for a larger library did little to dampen the spirits of Penn State administrators as they gathered with GSA and PWA representatives on February 26, 1938, to break ground for ten major structures: Physics, Electrical Engineering, Agricultural Engineering, Agricultural Science, and Poultry buildings, new wings for the Liberal Arts and Mineral Industries buildings, and the new library. When completed in 1940, these additions would increase the value of the physical plant by nearly 50 percent, to $16 million. Hunter and Caldwell of Altoona, GSA architects, were to collaborate with Charles Klauder in designing the buildings.

(Left) Agricultural Engineering Building, opened in 1940; (right) Initial unit of the building that in 1950 was designated Pattee Library.

President Hetzel, Governor Earle, GSA director Colonel Augustine Janeway, and other notables attended the groundbreaking ceremonies, held collectively in Recreation Hall. About 6,000 people gathered to hear their speeches, which were also carried live throughout Pennsylvania via an eight-station radio network. Governor Earle used the groundbreaking to resurrect an idea that in slightly different form had been put forth by John Thomas. "The Pennsylvania State College is absolutely a misnomer," he said in impromptu remarks at the close of his prepared speech, "because Penn State is not a college, it is a university; and Pennsylvania is not a state but a commonwealth." By simultaneously recognizing the real status of the institution and honoring the venerable English heritage of the term "commonwealth," asked Earle, would not the name University of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania be more fitting? (Four states-Massachusetts, Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania- then styled themselves "commonwealths.") The governor recommended that the Penn State community consider the name change and inform him of the conclusions.

In early March, the Collegian polled the students to assess their reactions. The results showed overwhelming sentiment for a change of name but not for the one Earle had submitted. Votes cast in favor of the University of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania totalled 107, versus 2,018 for The Pennsylvania State University and 61 desiring no change. Faculty and alumni also came out strongly for simply substituting "university" for "college." Opposition to the "commonwealth" designation rested largely on the length of the full name, and a lack of a convenient shorthand term. The revered "State" or "Penn State" would no longer be accurate, and "Penn" referred to the University of Pennsylvania, an institution with which the College was already frequently confused. And somehow "CU" just did not sound right. When Governor Earle learned of the overwhelming support for The Pennsylvania State University, he discarded the commonwealth idea and promised to do what he could to bring about the desired change. He instructed Attorney General Margiotti to explore the legal steps that must be followed if the institution were to change its name. Margiotti subsequently ruled that first Penn State's board of trustees had to approve the change, and then the Centre County Court of Common Pleas had to consent to it. (Both of these requirements had been met in 1873 when the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania became The Pennsylvania State College.) No legislative review was necessary.

President Hetzel called the proposition "a most interesting suggestion" but refused to commit himself to a definite course of action. This circumspection was typical of Hetzel's deliberate approach to important questions. (One faculty member fondly referred to him as the "hesitant pretzel.") It nonetheless contrasted sharply with the fervor he had shown at the University of New Hampshire, where he campaigned hard and successfully for a change of name. Hetzel did bring the matter before the trustees, however.

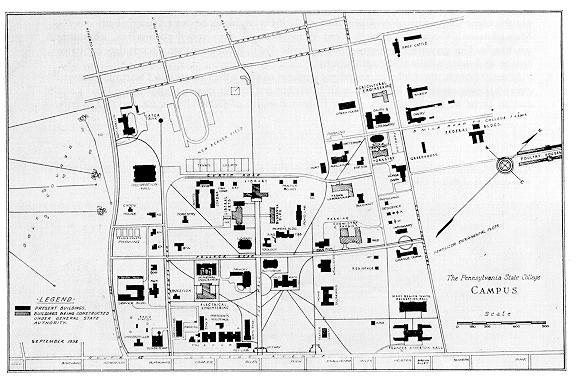

The campus in 1938.

Meanwhile, residents of the borough of State College began talking about the advisability of renaming their town, since State College seemed out of harmony with the proposed Pennsylvania State University. Mount Nittany, Atherton, Hetzelburg, Univer City ("accent the City"), and several other names were presented with varying degrees of seriousness. Residents eventually saw no reason to tamper with the borough's name, since Penn State's trustees could not agree on a course of action with regard to changing the name of the College.

In June 1938, the trustees tabled consideration of the name change until they convened for their next meeting in December. At that time, they discussed the possibility of substituting "University" for "College" and authorized the formation of a committee to study the question of securing some unspecified modifications in the institution's charter. The trustees apparently included a change of name as one of the modifications they were seeking, although why they did so is difficult to comprehend. The General Assembly had to consent to any alterations in the charter, yet Attorney General Margiotti's opinion as well as precedent placed the change of name issue outside the realm of legislative action. In any case, by linking the name change to other proposed charter changes, the trustees effectively nullified the chances of The Pennsylvania State College becoming The Pennsylvania State University in the near future. The political climate in Harrisburg began to change with the gubernatorial and legislative elections of 1938, and the time did not seen appropriate to make special requests of governmental leaders.

College officials hesitated to do anything that might identify the institution too closely with Governor Earle, who in the last year of his term was being bombarded with charges of presiding over the most corrupt administration Pennsylvania had endured since the late nineteenth century. Penn State made an effort to put space between itself and the governor, even though Earle had proven a good friend, His critics said he was also a good friend to those of his associates who would make graft a way of life in state government. In May of 1938, a Dauphin County grand jury convened to investigate alleged corruption in the Earle administration. Charles Margiotti, whom the governor had fired a month earlier because of political differences, gave the jurors information purporting to document this corruption, especially in the operations of the GSA. Penn State came under scrutiny when the county prosecutor claimed he had evidence showing that McCloskey & Company of Philadelphia, general contractors for all construction at the College, had bribed state inspectors to overlook shoddy workmanship or in some cases had brazenly replaced state inspectors with the company's own men. These allegations had obvious political overtones, since the prosecutors were Republicans and Matt McCloskey, president of the contracting company, was state Democratic Party treasurer and a close friend of the governor. In an exclusive interview with Collegian reporters, published September 30, 1938, McCloskey vehemently maintained his innocence, saying "If the authorities of The Pennsylvania State College have any doubt about the quality of work which my company is doing on the campus, I shall cheerfully pay for any test which they feel should be made. " In October College Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds George W. Ebert was called to Harrisburg to testify before a special legislative committee that had been set up after the grand jury began uncovering evidence of serious misdeeds. Ebert said that neither he nor his assistants had ever had reason to believe the contractors willfully tried to subvert construction standards and that all work was being done according to regulations. After that testimony, public attention shifted away from the College to other institutions with which the GSA was connected.

Civil engineering camp at Stone Valley, about 1940