Browse the Collection

Search the Collection

View Finding Aids

Washington Literary Society records, 1859-1895About the Collection

Photosphere

The Photosphere appears to be a single volume publication of the Washington Literary Society from 1874. The Photosphere contains a brief history of the society, miscellaneous humor, and essays. The Washington Agricultural Literary Society (later, the Washington Literary Society) formed simultaneously with the Cresson Literary Society in March 1859, only a few years after the founding of the Farmer’s High School. The entire all-male student body were members of one or the other of the two societies. The Washington Literary Society named itself in honor of George Washington. Both societies received a $250 appropriation from the state legislature to create libraries for the benefit of their members. Antebellum collegiate literary societies functioned as an adjunct of the official educational curriculum. Members participated in competitive debates and essay writing and oratorical contests. In the late nineteenth century, the rise of fraternities, organized athletics, and other kinds of clubs gradually diverted interest from the literary societies, leading them to disband in 1895.

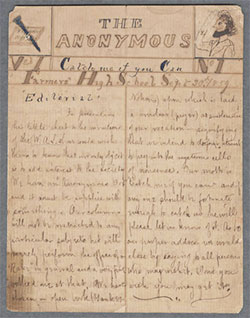

Anonymous

This collection consists of four issues and an extra edition from the first volume of the Anonymous, a newspaper that collected anonymous gossip about students and faculty. Members of the Washington Agricultural and Literary Society launched the Anonymous in 1859 in the hope that it would increase interest in the society. Milton Lytle of Spruce Creek, whose digitized diaries are also available on the People’s Contest site, was an editor of the Anonymous during his tenure at the Farmer’s High School, beginning in 1860. The Anonymous was modeled after what was known as the “flash press.” The flash press emerged in New York City in the 1840s and was marketed to young sporting men whose pastimes often included gambling, drinking, and brothel-going. By writing about such pursuits the flash press mocked popular moral reform newspapers of the period and criticized social elites who presented a public image of respectability but who were privately scurrilous in their behavior. These papers’ salacious content included gossip items that anonymous readers could place in the papers as ads under the heading of “wants,” as in the reader “wants to know” if this gossip is true. The Anonymous similarly published unattributed gossip about students’ activities on such topics as their attempts to court local women, their travel to surrounding towns primarily to procure alcohol, and even their sexual encounters (addressed indirectly in euphemistic terms).