John Oswald served Penn State for thirteen years, retiring on June 30, 1983. One of his last major administrative acts was to approve a return to a semester calendar.

The University's term system had never been completely satisfactory, even after the late September starting date for fall term had been advanced by several weeks beginning in 1973. There were too many expensive and time-consuming registration and examination periods. Many students and faculty found the 75-minute class periods to go beyond normal attention spans and the ten-week terms to be too brief to permit adequate preparation of research projects. The large summer enrollment, the main reason for the switch to the term system, had never materialized.

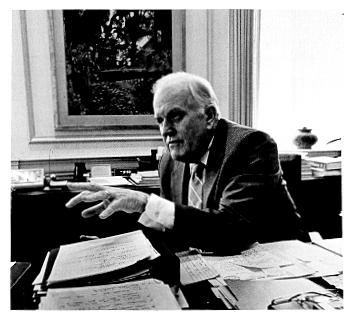

Bryce Jordan, Penn State's fourteenth president

The implementation of the new calendar came during the first year of the administration of the University's fourteenth president, Bryce Jordan, formerly Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs at the University of Texas. The trustees had elected Dr. Jordan in October 1982 after a long and careful search that involved board members, faculty, and students.

The 58-year-old Jordan was born in New Mexico and raised in Texas; he graduated from the University of Texas in 1948 with a bachelor's degree in music education. He earned a Ph.D. in historical musicology from the University of North Carolina in 1956 and taught at several other universities before returning to the University of Texas at Austin in 1965 to head the music department. Three years later, he became that institution's Vice President for Student Affairs and in 1970-71 served as its acting president. Jordan amply demonstrated his administrative capabilities during the ten years he was president of the University of Texas at Dallas. He oversaw the school's transformation from a single building and forty students to a modern metropolitan campus and 7,000 students. By the time he left in 1981 to take the vice chancellor's post, the University of Texas at Dallas had become a leader among the state's public institutions in the amount of funds it raised through private grants, gifts, and endowments, and in the quantity of per-faculty research dollars it received.

The change in Penn State's top leadership gave the University renewed stamina to meet the challenges of the 1980s and beyond. Among its more urgent tasks, the institution had to combat rising costs in nearly every category without relying more heavily on state appropriations or federal support, neither of which showed immediate prospects of increasing significantly. It had to devote additional resources to research and graduate work until its reputation for excellence encompassed more than a few fields. Means had to be found to deal more efficiently with shifting student curricular interests while preserving the depth and breadth of traditional university scholarship. Plans had to be made to attract more minority students, to stay abreast of technological change in classrooms and laboratories, and to adapt the Commonwealth Campus system to new patterns of enrollment.

Governor Dick Thornburgh chats with students during a visit to University Park.

The change in leadership did not alter Penn State's commitment to its tripartite mission of teaching, research, and public service. Financial constraints did adversely affect the University's ability to perform that mission; but to what extent, only the further passage of time would reveal.

THE MISSION

Instruction in the classroom and laboratory remained Penn State's primary activity. One Pennsylvanian in eight who chose to enter college immediately after high school in the 1970s enrolled at University Park or one of the Commonwealth Campuses. More than 110,000 baccalaureate degrees were awarded between 1970 and 1983, along with 21,000 associate and 27,000 graduate degrees. By 1982, one in every thousand college graduates in the United States had earned his or her degree from The Pennsylvania State University.

In 1973, the board of trustees made excellence in teaching one of the criteria for the Evan Pugh professorships, the highest honor the University could bestow upon its faculty. Authorized in 1960, the Pugh professorships had heretofore been conferred on the basis of a faculty member's long-term research accomplishments. Under the revised standards, candidates had to demonstrate sustained achievements in research or creativity outside the classroom, and give evidence of having contributed significantly to the education of students who later won distinction in their own right in the disciplines in which they had studied. Appointed by the president upon recommendation by a special faculty committee, the Evan Pugh professors were an elite group: only twenty-four were selected between 1960 and 1983. Recipients gained prestige within their profession, higher salaries, and a degree of independence from normally assigned duties in their academic departments.

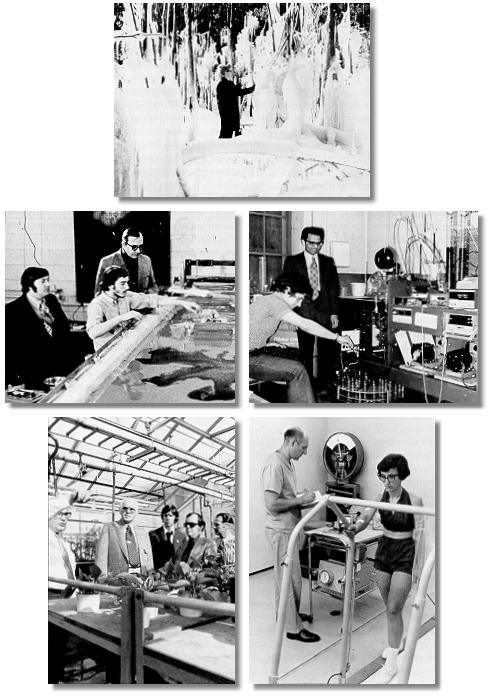

(Top) A winter wonderland of frozen sewage effluent, sprayed continuously on portions of University lands as part of a "living filter" experiment aimed at purifying and conserving water resources; (center left) Earth and Mineral Sciences researchers with a model of the oil harvester, designed to clean up spills in oceans and other waterways; (center, right) the energy crisis of the 1970s gave rise to all kinds of investigations, including this apparatus for extracting oil from tar sands; (bottom, left) studies in plant pathology are described to visiting state legislators, 1972; (bottom, right) testing women's tolerance to heat stress was an early topic for investigation at the Human Performance Laboratory.

The Evan Pugh professors symbolized the intellectual diversity of Penn State. Vernon Aspaturian, Evan Pugh Professor of Political Science and director of the Slavic and Soviet Language Area Center, was an internationally acknowledged authority oil the political system and foreign policy of the Soviet Union. A veteran (since 1952) Penn system and foreign policy of the Soviet Union. A veteran (since 1952) Penn State teacher, he had traveled and studied extensively in the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe and authored or coauthored dozens of books, articles, and reviews dealing with Soviet bloc politics. Art of the Italian Renaissance was the principal field of study for Eugenio Battisti, Evan Pugh Professor of Art History. Born in Italy and educated at the University of Rome, Battisti held a number of visiting professorships in America and in his native land both before and after Joining the Penn State faculty in 1965. Several of his monographs on Italian Renaissance art became the standard works in their field.

Hershel Leibowitz, Evan Pugh Professor of Psychology, won wide acclaim for his investigations in experimental and applied psychology, especially the area of visual physiology and human perception. His research on topics related to transportation safety included studies of the behavior of motorists involved in auto-train collisions, night myopia, the vision of pilots, and the design of aircraft instrument panels. After being named a Pugh professor in 1974, Leibowitz continued to teach introductory psychology courses to undergraduates, in addition to serving as a consultant to a half-dozen government agencies and holding editorial posts with several leading academic publications. Another distinguished teacher-researcher was Evan Pugh Professor of Chemistry Phillip Skell, who in 1977 (three years after being named a Pugh professor) was chosen by students as the outstanding undergraduate teacher in the College of Science. Known among his colleagues worldwide as the "father of carbene chemistry," Skell also researched the behavior of free metal atoms-work which led to the creation of a new basic chemistry of free atoms. He became the third member of the Penn State faculty (after Frank Whitmore and Erwin Mueller) to be elected to the National Academy of Science.

The investigations of Richard R. Nelson, Evan Pugh Professor of Plant Pathology, were of a more applied nature. Since Joining the faculty in the College of Agriculture in 1966, he had earned high professional repute for his studies in plant genetics, the evolution of plant pathogens, disease resistance in plants, and plant epidemics. Nelson made important strides toward solving a genetic riddle which would lead to the breeding of wheat and rice strains more resistant to the fungal diseases that destroyed much of the world's food supply. Howard E. Morgan, on the other hand, was interested in treating diseases in humans. Evan Pugh Professor of Physiology and chairman of the College of Medicine's Department of Physiology since 1967, Morgan utilized grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Heart Association to investigate the action of insulin, glucose, and certain chemical processes in the body. Like nearly all the Evan Pugh professors, he had a worldwide reputation. He led the American delegation to the fourth U.S.-U.S.S.R. Symposium on Myocardial Metabolism and served a term as president of the International Society for Health Research.

As befitted a land-grant university, most of the research at Penn State had practical implications. Much of it was also multidisciplinary, combining the talents of specialists in a variety of departments and colleges.

The development and use of various forms of energy, for example, comprised significant parts of the research programs of many of the colleges. In the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, faculty continued their longtime efforts to make coal mining safer and more efficient. A Methane Research Group was established to study methods of extracting the volatile methane gas that was found in underground coal mines and to assess the possibility of using it commercially. Mineral economists and mining engineers examined the feasibility of constructing mine-mouth electric generating stations in Pennsylvania's anthracite region. In both the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences and the College of Science, men and women worked to improve coal gasification and liquefaction techniques, thereby enhancing the nation's energy independence. In the Department of Chemical Engineering in the College of Engineering, investigators developed processes that allowed tertiary recovery of Pennsylvania-grade crude oil deposits. Older recovery methods left as much as 50 percent of the oil below ground. Meanwhile, agricultural engineers were attempting to devise a satisfactory means of injecting methanol (wood alcohol) and ethanol (grain alcohol) into diesel tractor engines, thereby forming a "closed farm loop" energy system.

Researchers were also concerned with the environmental impact of energy development and use. Scientists and engineers at the Materials Research Laboratory were trying to eliminate some of the dangers associated with the disposal of solid nuclear waste. Disposal techniques that showed promise included immobilizing the waste within pellets of insoluble artificial minerals (thus preventing release of radiation) and burying it underground in specially designed ceramic containers. A team of scientists in the Pennsylvania Fish and Wildlife Research Unit in the College of Agriculture (earlier in the College of Science) was one of several University groups working on the problem of acid rain, the fallout from chemicals poured into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. Unit researchers measured the present and potential damage caused by acid rain to the fresh waters of the mid-Atlantic states and made recommendations to protect the headwaters of selected streams. Investigators in the College of Science and the College of Earth and Mineral Sciences were searching for better and cheaper means of reducing sulfur emissions from coal, either when burned as a solid or during its liquefaction and gasification stages. Studies were under way at the Institute for Research on Land and Water Resources to improve the handling of acid drainage from coal mines and the reclamation of strip-mined lands.

Health care and medicine was another area that commanded the attention of a cross-section of University researchers. While maintaining a strong commitment to family medicine, the Hershey Medical Center in the 1970s evolved into an institution equally well-known for the breadth of its research. Sleep disorders, herpes simplex virus, pregnancy toxemia, and hyaline membrane disease were only a few of the subjects under investigation. Hershey had an extensive, well-financed series of programs under way to discover the causes of cancer, improve its early detection, and find more effective methods of treating its victims. The animal research farm, expanded in 1976, facilitated investigations in such fields as neurosurgery, reproductive biology, and cardiac metabolism. Physicians and bioengineers depended heavily on the farm in their efforts to perfect heart pumps, valves, longer-lived pacemakers, and artificial organs. Ventricle assist devices, by-products of attempts to develop an entirely man-made heart, were first used to save the lives of open-heart surgery patients in 1977. About that same time, artificial hearts began to be implanted in calves with encouraging results. Transplants using the hearts of human donors were first performed in 1984.

From chemistry research in the College of Science came new types of plastic that could be used for heart valves and blood vessel sections, as well as a more effective method of treating angina pectoris, a painful heart condition caused by blocked arteries. The new means of treatment consisted of administering medication through an adhesive bandage rather than orally via tablets. At the Noll Laboratory for Human Performance Research and the Sports Research Institute in the College of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, specialists in physiology, physical education, and engineering tested the limitations of defibrillators used in reviving heart attack victims, probed the causes of obesity in order to establish safe weight reduction models, and studied correlations between physical exercise and cardiovascular diseases. The Institute's National Athletic Injury/Illness Reporting System (NAIRS), begun in 1974, contained the largest collection of data in the nation pertaining to the when, where, why, and how of injuries to secondary-school and college athletes. In the College of Agriculture food scientists investigated cholesterol inhibitors in milk and found evidence to dispute the claim that drinking whole milk causes the body's cholesterol levels to rise.

Research did not have to utilize complex technology to be significant. Faculty in the College of Human Development systematically observed the impact of television violence on preschool children, and scrutinized the social and psychological factors that made the process of separation and divorce a smooth or difficult one. The College's Gerontology Center promoted University-wide research on such subjects as motor memory and the aging process, and the elderly's special demands on mass transportation systems. In the College of Education, tests were developed that more accurately measured the intelligence of mentally handicapped persons, showing that many children previously thought beyond help could still be taught to carry on certain fundamental activities in life. A group of researchers in the College of Business gathered data on twenty-six lines of insurance from a thousand companies to formulate a statistical measure of the riskiness of each line. The data helped the companies determine the amount of surplus funds needed to write each line, thus enabling them to manage their capital more efficiently.

Nor did worthwhile research have to have utilitarian implications. The quest for knowledge for its own sake was alive and well at Penn State, whether it motivated microbiologists who studied the various phases of recombinant DNA technology ("gene splicing") or astronomers who were cooperating with NASA and Cal Tech to develop an orbiting telescope that could take x-ray pictures of black holes. The College of Liberal Arts possessed faculty with national reputations on topics spanning the gamut from science fiction writing to the primitive Indian tribes of Venezuela, from American folklore to the American Civil War.

Faculty creativity was also apparent in the College of Arts and Architecture. The arts had long thrived at Penn State, but in the 1970s, they came of age, taking a place alongside the University's more highly publicized technical achievements.

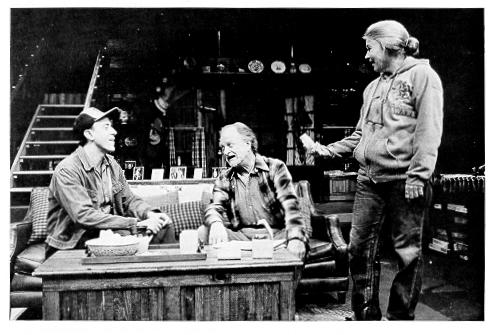

A scene from On Golden Pond, a 1981 production of the Festival Theatre.

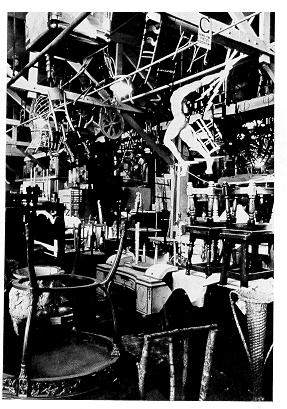

Theatre Arts prop room

The theatre arts flourished. In 1970, the Festival Theatre was launched, using the professional-quality facilities of the Playhouse and the Pavilion Theatre. Staging several productions every summer, the Festival Theatre employed Equity actors recruited from New York auditions and the resident theatre circuit, together with a select group of theatre department students and faculty. A year-round program of plays drawing upon the talents of professionals, students, and faculty was introduced in 1979 with the formation of the University Resident Theatre Company. Both the Festival Theatre and the URTC proved to be fine training grounds for students while reinforcing the faculty's professional discipline without making them travel far from home. Student playwrights had an opportunity to present their work in yet another program, the Five O'Clock Theatre, which ran periodically throughout the academic year.

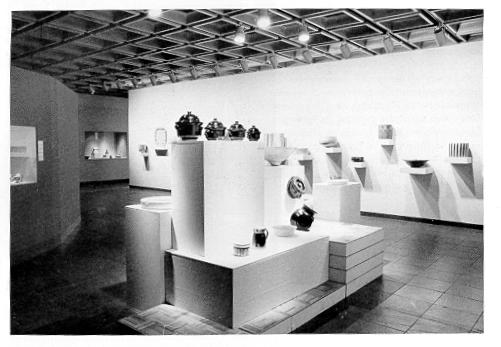

One of the cornerstones of the arts at Penn State was the Museum of Art, completed in 1972 at a cost of $3 million. The University's first full-fledged art museum, it regularly showcased exhibits by internationally famous artists. And thanks in large part to the dedicated efforts of the Friends of the Museum, it also began acquiring a permanent collection of paintings, drawings, and sculpture that grew remarkably in quality and quantity over the first decade of the facility's existence.

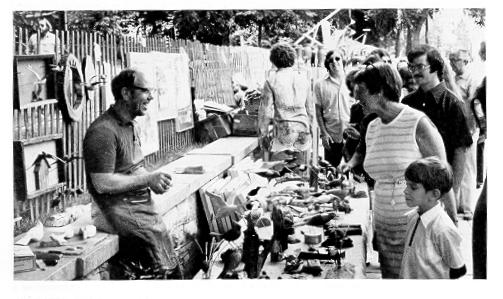

No artistic event was more diverse or won more favor with the general public than the Central Pennsylvania Festival of the Arts, which the College of Arts and Architecture launched in 1967 in cooperation with local artists and civic leaders. A week-long event held each July, the Arts Festival featured the work of over 350 artists and craftsmen who displayed their painting, pottery, leather goods, and other items in open-air booths strung along campus walks and downtown thoroughfares. Within a decade, this all-juried show was attracting exhibitors from coast to coast. But the Festival celebrated all of the arts. Its fiddling contests, live theatre, poetry readings, rock music, dance, and much more delighted 200,000 visitors each year by the early 1980s.

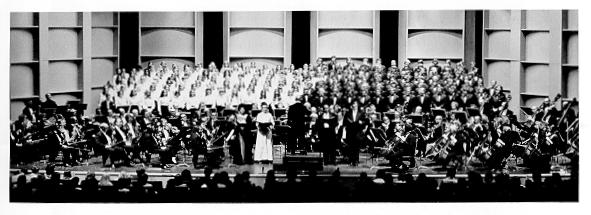

Another event whose appeal extended beyond the University community was the Artist Series. Tracing its origins to the Artists Course of the 1930s, the series by the 1970s brought to University Park talented performing artists ranging from Itzhak Perlman and Johnny Cash to the Leningrad Philharmonic and the Broadway musical "Godspell." The world premiere of a musical commemorating the American bicentennial, "Be Glad Then America," written by Pulitzer Prize winner John LaMontaine and directed by the renowned Sarah Caldwell, was staged as part of the Artist Series in 1976. (The work was specially commissioned by the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies.)

Display of Danish ceramics, Museum of Art.

The College of Arts and Architecture also took the performing arts to the people. The Alard String Quartet, Children's Theatre Ensemble, Brass Chorale, and similar groups made frequent appearances throughout the Commonwealth. Some toured nationally and occasionally even went abroad.

Artists and browsers crowd the sidewalk at the Central Pennsylvania Festival of the Arts.

A boon for research and learning in all of the colleges was the computerization of the University libraries, begun in 1975. The libraries' holdings, except for those in a few specialized areas, were still inadequate for an institution the size of Penn State. However, computerized acquisitions, cataloging, and circulation resulted in more efficient response in less time for patrons, reduced operating costs, and put the University in the forefront of library automation. Computers linked Pattee Library with branch libraries at University Park and the Commonwealth Campuses, and plans were being readied to install terminals in individual departments, offices, and residence halls. Patrons also had access via computer to the bibliographic resources of the Research Libraries Group (a consortium of the nation's leading research institutions), thus partially offsetting the limitations of the University's own collections.

In pursuance of the traditional role of university presses as extensions of their parent institution's research function, The Pennsylvania State University Press entered a period of expansion in 1973. Reinvigorating its seventeen-year-old commitment to disseminate research-based contributions to scholarship from the faculty at the University (and from scholars at other institutions), the press enlarged upon the kinds of books and journals it published and produced especially noteworthy titles in art history, conservation, literary criticism, American history, plant pathology, meteorology, and Victorian studies. Penn State Press also assumed a secondary role of publishing informational works that appealed to a broader readership. Perhaps best exemplified by the University's official bicentennial book, Pennsylvania 1776, these popular titles touched upon topics as diverse as Pennsylvania history and politics, nature lore, crafts, and sports safety.

The University Choirs perform with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in celebration of the opening of the University Auditorium, May 1974.

A sampling of a few specific projects cannot do justice to the size or diversity of the research and creative activities found in any of the University's colleges. Neither can it adequately characterize the obstacles encountered by Penn State as it struggled to provide a satisfactory level of financial support for research. Total expenditures for organized research climbed from $33 million in 1968-69 to $57 million in 1978-79; yet, when these figures are adjusted for inflation, Penn State spent $1 million less on research in 1978-79 than it had ten years earlier. It barely remained among the nation's twenty largest research universities. The heavy demands of instruction continued to restrict, as they had for decades, the amount of money available for other purposes. In the face of economic belt tightening by state and federal governments, the University increasingly had to rely on the private sector to sponsor research and to furnish the hardware needed to keep pace with technological change.

To fulfill the third aspect of its mission-public service-Penn State used a battery of continuing education, cooperative extension, community service, and correspondence programs every bit as diverse as its research programs. Through them, the University promoted the cultural and professional advancement of out-of-school youths and adults, and provided educational and advisory services to assist government, business, and the public in the solution of social, economic, and technical problems.

Thousands of students each year earned college credits by taking correspondence courses or evening classes through the Division of Continuing Education, but many of the 300-odd correspondence or "independent learning" courses carried no credit. They were designed to satisfy personal interests (Intermediate Stamp Collecting, offered in cooperation with the American Philatelic Society) or to meet specific practical needs (a series of lessons on the fitting of automatic fire sprinklers, co-sponsored by a union local and a trade association). The continuing education staff also coordinated a long list of seminars, conferences, and institutes at University Park and other locations. At the main campus alone, a single year's schedule might include workshops on hardwood lumber grading and inspection, and microcomputer literacy; annual meetings of the Pennsylvania Ceramics Association and State Association of Arson Investigators; a leadership conference for the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees; and a symposium on storm water management.

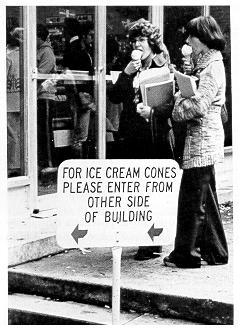

The Creamery—one of the highlights of any visit to University Park.

Continuing education specialists also worked within the individual colleges to provide a wide array of educational programs for nontraditional students. One of the most popular in the College of Agriculture was the ice cream technology short course. Taking advantage of the college's longtime expertise in the manufacture of ice cream (since the 1890s) and its modern, well-equipped creamery, the short course ran for two weeks each year and consistently enrolled personnel from Baskin-Robbins, Borden, Sealtest, and other industry giants in America and Europe. Among the most highly regarded continuing education services of the College of Business Administration was its Executive Management Program. Oriented toward experienced middle-level managers who wanted and expected to become the senior officers of their firms, the basic program consisted of four weeks of intensive lectures, seminars, and roundtable discussions focusing on the development of leadership skills and management strategies. Limited to about fifty students per session (there was nearly always a waiting list), the objective was to get the participants to learn from each other as much as from their instructors. As in the case of the ice cream short course, the Executive Management Program had an international clientele; thirty-nine countries were represented at the 1982 sessions. Faculty in the College of Health, Physical Education, and Recreation worked with an entirely different kind of student body in the summer sports camps, another extremely popular continuing education service. The camps offered instruction in a dozen or more sports to youths, mostly teenage, of both sexes, who came from throughout Pennsylvania and neighboring states. Participants lived in residence halls during the one- to two-week sessions and received expert supervision from the Penn State coaching staffs.

The oldest of the University's community service programs, the Cooperative Extension Service, embodied the same fundamental objectives in the 1980s that it had when the system of county agents and agricultural and home economics specialists was introduced early in the century: to improve the income-producing skills and quality of life for the Commonwealth's citizens, particularly those in rural areas. Helping farmers to produce more efficiently and cope more effectively with the marketplace remained one of Extension's primary chores. County agents and other specialists also performed such varied tasks as answering 200,000 queries a year about home gardens and lawns, advising the150,000 young Pennsylvanians enrolled in 4-H clubs, and organizing community programs on topics ranging from energy conservation to good nutrition.

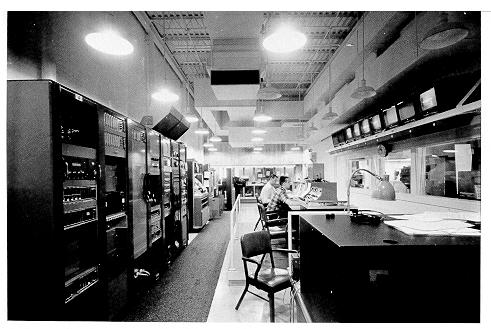

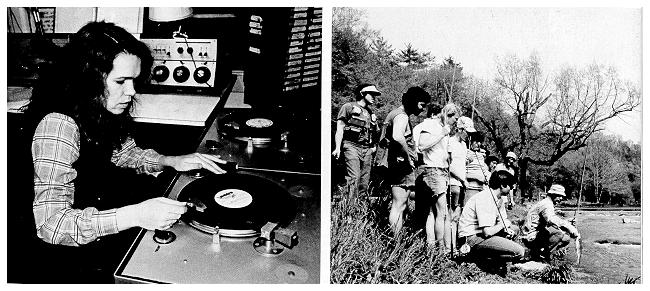

WPSX control room, Wagner Building.

Another far-reaching community service effort relied on the latest technology in cable television. PENNARAMA, the world's largest interactive cable television network at the time it became fully operational in January 1983, carried a 24-hour schedule of credit and noncredit adult education courses. Virtually all of Pennsylvania's cable systems, having a total subscribership of 1.5 million viewers, had access to PENNARAMA via a microwave system based at University Park. Penn State managed the service on behalf of all institutions of higher education in the Commonwealth. Television station WPSX, another important electronic tool for continuing education and public service, remained wholly owned and operated by the University. Weekdays it presented mainly programming for elementary and secondary school children. Evenings and weekends, it broadcast some adult education courses along with a potpourri of informational, cultural, and entertainment programs. It was central Pennsylvania's primary outlet for the Public Broadcasting Service and the Pennsylvania Public Television Network.

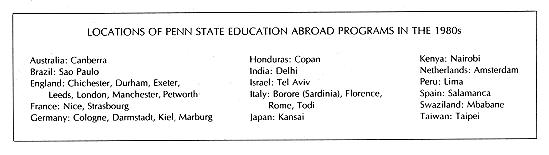

The University Office of International Programs (UOIP) blended Penn State's teaching, research, and public service missions. Continuing a tradition begun in China in 1911, UOIP served the needs of some 400 "homegrown" students studying abroad, some 2,000 foreign students studying at Penn State, and participants in more than forty worldwide cooperative ventures in teaching and research.

ATHLETICS

There was no slackening of student, alumni, or public interest in athletics in the 1970s. Intercollegiate sports became a more conspicuous feature of the University scene than ever before.

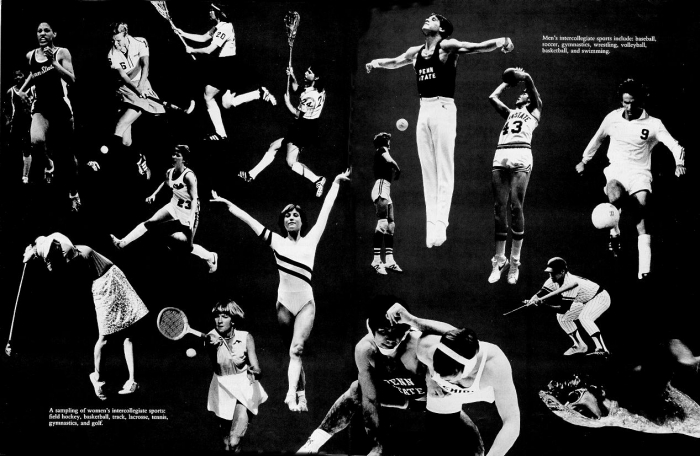

Some of this prominence resulted from the rise of women's varsity sports. Amendments made by Congress to federal aid to education policies (mainly Title IX of the Higher and Secondary Education Act) in the early 1970s prohibited sex discrimination in any program or activity that benefited from federal funds. As interpreted by the courts and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the ban on discrimination included athletics as well as admissions policies and employment practices. This interpretation gave a tremendous boost to women's intercollegiate sports nationwide.

Title IX caused panic and radical policy shifts at some institutions; at Penn State, it merely accelerated changes already under way. The University had already progressed from having women "participate" in athletics-which had been the norm since the Women's Recreation Association was founded in 1918-to having them "compete," as the men had been doing since the nineteenth century. Women had been engaging in officially sanctioned intercollegiate sports since 1964, when the first contests were held in basketball, fencing, field hockey, golf, and gymnastics. In 1972, University representatives helped to found the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, which attempted to do for women what the NCAA had done for men.

(Above) Women's field hockey on Beaver Field, 1920s; (below) women's physical education in the 1930s—instruction in dance.

Following the implementation of Title IX, the University gradually upgraded physical facilities and equipment, provided financial assistance to meet travel, coaching, and other costs, and beginning in 1974 offered athletic grants-in-aid. Teams were fielded in nearly a dozen sports, many of which rivaled men's events in popularity-women's gymnastics usually ranked second to football in attendance for home contests. Through 1980-81, Penn State had won more major college national championships (nine) in women's sports than any other institution in the nation.

(Left) A sampling of women's intercollegiate sports; field hockey, basketball, track, lacrosse, tennis, gymnastics, and golf. (Right) Men's intercollegiate sports include: baseball, soccer, gymnastics, wrestling, volleyball, basketball, and swimming.

In men's varsity sports, teams in cross country, football, gymnastics, soccer, and wrestling regularly appeared in NCAA national play-off competition. In 1978, the University undertook a campaign to become a nationally respected power in basketball. Efforts were made to draw more alumni and other nonstudents to home games, and hopes were raised that a number of "blue-chip" high school players could be recruited. Dick Harter, who had rebuilt floundering programs at Penn and the University of Oregon, was brought in as head coach. Harter's labors at Penn State were not as successful, although his teams posted a cumulative record of 79 wins and 61 losses before his departure at the end of the 1982-83 season.

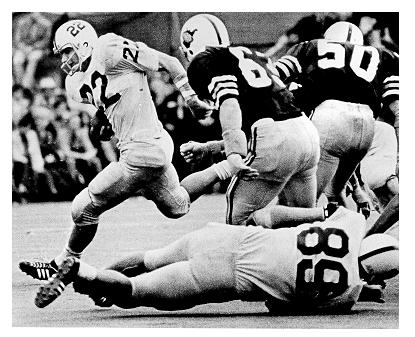

Football continued to reign as the University's premier sport in both the popular interest and the revenue it generated. Beaver Stadium underwent successive expansions until it had a capacity of about 83,000 by 1982, and even then the demand for tickets could not be met. Rip Engle retired as head coach in 1966. Under his successor, Joseph V. Paterno, who had accompanied Engle to Penn State from Brown in 1950, the Nittany Lions evolved from a regional power to a national one, appearing in sixteen Post-season bowl games between 1966 and 1984. On January 1, 1983, the Nittany Lions defeated the University of Georgia Bulldogs in the Sugar Bowl at New Orleans to become the nation's top ranked football team for the first time in their history.

1973 Heisman Trophy winner John Cappelletti in action against the West Virginia University Mountaineers.

All participants in intercollegiate sports were expected to be students first and athletes second. They were encouraged to partake of the sundry academic and social experiences that came with a college education; for this reason there were no residence halls reserved exclusively for athletes, no easy courses created especially for athletes who were floundering academically, and few other perquisites normally associated with big-time college sports. There were nonetheless concessions to the pressures of national competition, particularly in football. Freshmen were allowed to play in varsity contests, and "redshirting" (the practice of withholding players from participating for a year, to allow them to mature or to recover from physical injuries) did occur.

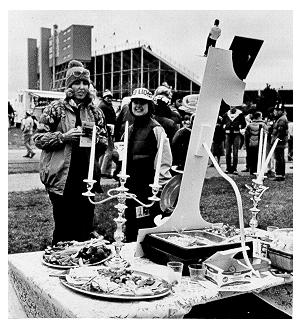

Long a tradition at Beaver Stadium, tailgating before and after each football game could reach elaborate proportions.

The concept of producing consistent winners on the playing field without compromising academic standards was not a new one. Its foundation lay in the reorganization of the athletic program in the late 1920s. The University found it had transgressed the bounds of realism by implementing the Beaver White recommendations to the very letter; but even when it again modified its athletic policies after World War II, it still clung to the spirit that motivated the initial reforms. Milton Eisenhower and Ernest McCoy insisted that intercollegiate athletics remain subordinate to academic authority. In later years, both Eric Walker and John Oswald were careful to adhere to that same policy.

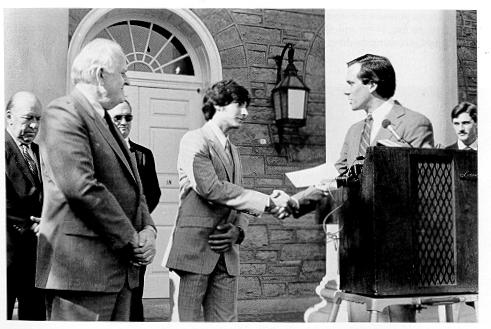

With President Jordan looking on, Lt. Governor William W. Scranton III presents a check to the one millionth Pennsylvania borrower in the Guaranteed Student Loan Program, Penn State graduate student Joseph Palermo.

Another concept from the 1920s-athletics for all-also left an enduring imprint. Penn State continued to have one of the largest and most highly organized intramural sports programs on any campus, and it remained firm in its commitment to sports as a purely recreational pursuit. In the 1960s and 1970s, there appeared such notable physical improvements as a new building for intramural sports, additions to the White Building and the Recreation Building, a new 18-hole golf course (the Blue Course), and lighting systems for outdoor intramural fields.

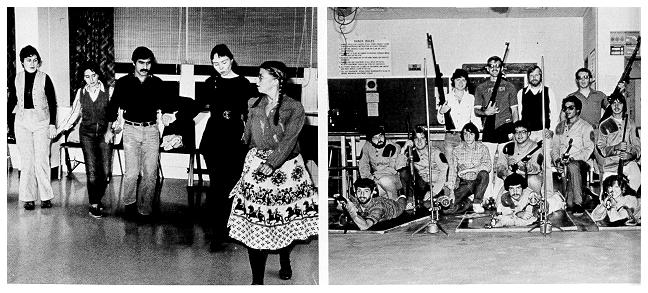

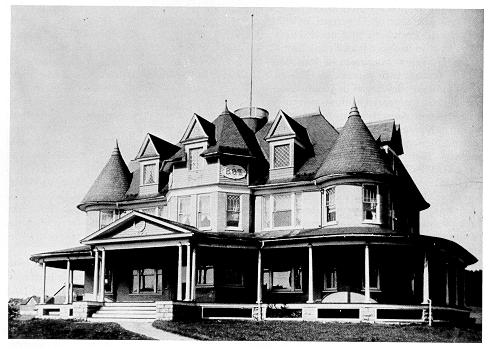

The Daily Collegian (left) is one of the many organized extra-curricular activities available to students at University Park, which also encompass such diverse interests as (below, top left to right) folk dancing, rifle club, (below, bottom left to right) WDFM (since 1984, WPSU), and a chapter of Trout Unlimited.

According to periodic surveys made under the auspices of the American Council on Education, Penn State in the 1970s and the early 1980s was still a "first generation" land-grant school. A sampling of incoming students in 1976, for instance, revealed that 50 percent of their fathers and 64 percent of their mothers had never attended college. Those figures compared with national averages that year of 33 percent and 45 percent, compiled from a survey of 51 large public universities. Penn State students also had a significantly greater than average share of fathers and mothers who had terminated their formal education prior to high-school graduation.

The University continued to draw large numbers of able students, whatever the educational backgrounds of their parents. In 1979-80, a typical year, 47 percent of all males and 64 percent of all females who began undergraduate studies had ranked in the top one-fifth of their high school class (compared with 46 percent and 59 percent twenty years earlier). Throughout the decade, approximately nine out of ten Penn State students were residents of the Commonwealth, although virtually every other state in the union and its territories were also represented. New Jersey, New York, and Maryland accounted for the majority of out-of-state students. There were also in residence nearly 2,000 foreign students from 105 nations, mostly at University Park.

Tremendous opportunities for academic and social enrichment awaited incoming students. They could choose from more than 30 associate, 180 baccalaureate, and 120 graduate degree programs. At the undergraduate level alone, 4,900 different courses were offered at University Park, Behrend, Capitol, and the Commonwealth campuses. And under the foreign studies program, in existence since 1962, students could spend up to an entire academic year at colleges and universities in England, Israel, Kenya, Taiwan, or a dozen other countries.

Opportunities for personal enrichment beyond the classroom were especially diverse at University Park. There were many student prevocational groups, some with venerable heritages. The Horticulture Club and its predecessors, for example, had been designing, managing, and promoting the annual fall Horticulture Show-a lavish exhibition of flowers and vegetable plants in imaginative settings that attracted thousands of visitors-since 1928. By contrast, the Penn State Chapter of the Society of Women Engineers-founded to encourage women to enter the engineering profession and enhance their career development-dated from the mid-1970s. Many clubs and associations were organized purely along lines of recreational interests, such as the Penn State Outing Club, with divisions dedicated to bicycling, hiking, sailing, mountaineering, and canoeing; the Monty Python Society, composed of devotees of a peculiar brand of British humor; the Penn State Model Railroad Club, with a permanent layout in the HUB subbasement; Eco-Action, which sponsored materials recycling and other environmental projects; and the Thespians, carrying on a theatrical tradition begun in 1897.

Beta Theta Pi House: first fraternity house to be built on campus (1895) and predecessor of nearly fifty additional house son and off campus by 1985.

Social fraternities, after weathering some insecurities at the end of the 1960s-when many students considered them tradition-bound and irrelevant-underwent a strong revival in the middle of the next decade. The built-in social life of fraternities, along with room and board costs that were increasingly competitive with the rising expenses of apartment living, made them more appealing to a new generation of students less inclined to challenge established values. With 49 chapters in 1976, Penn State stood second only to the University of Illinois in the number of active fraternities on its campus. They normally encompassed 12-14 percent of male undergraduates, also one of the highest proportions on any campus. Sororities, which still had no off-campus housing, were not quite so popular, although they too enjoyed a revival beginning in the mid-1970s. Sororities normally accounted for about 8 percent of the female undergraduate population.

The rising cost of living also brought about the renewed popularity of residence halls at University Park. The number of applicants consistently outweighed the number of available rooms, and the University encountered some trouble in devising a selection system that was both fair to students and administratively practicable. Strong social ties were by no means absent in the dormitories, especially in "interest houses" (portions of residence halls reserved for students having related academic majors or other shared interests) or on floors occupied by students coming from the same Commonwealth campus or geographic area. The University administration resisted the idea of coeducational living in residence halls, however.

Students at University Park enjoyed cultural and entertainment offerings usually associated with campuses in metropolitan areas. Besides Artist Series events, a variety of headline musical and comedy acts were regularly brought to the campus by the student-run University Concert Committee. Another student organization, Colloquy, sponsored informational lectures and services that likewise featured nationally known figures.

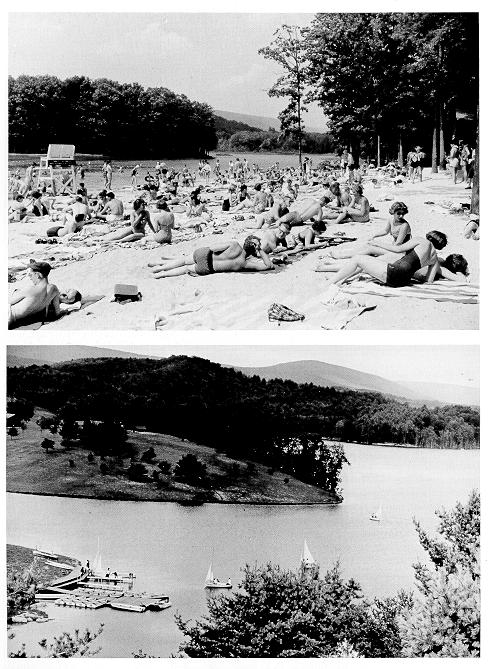

For those who preferred outdoor activities, there were a number of state parks and nature areas within easy driving distance of State College; among these, Whipple Dam was long a favorite of Penn State students. The University also had its own recreation area at Stone Valley, a tract that took in about 700 acres of land originally purchased in the 1930s. Development of the area had commenced in the late 1950s and was climaxed in 1961 by the construction of a dam across Shavers Creek. Stone Valley was open to University personnel and the general public for boating, picnicking, and camping, as well as for nature study and other educational uses.

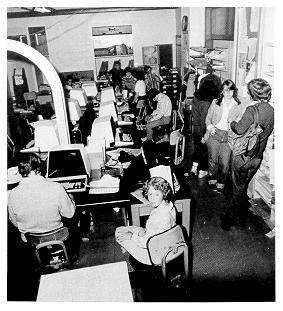

Dorm contract line for West Hall. Throughout the 1970s, a first-come, first-served system of securing residence hall rooms for fall term made scenes such as this one all too common during the preceding spring term.

(Top) Whipple Dam State Park—in the 1950s, as in later decades, a favorite recreation site for Penn State students; (bottom) Stone Valley, where boating has long been one of the most popular pastimes.

In the realm of social events and organizations, the 1970s saw the disappearance of some traditions and the birth of new ones. Gone was Spring Week, a series of festivities eagerly anticipated by students twenty years earlier. Long before its official demise in 1979, it had lost the float parade, he-man contests, carnival, and Miss Penn State coronation that had made it a community as well as University celebration. Superseding it was Greek Week, a scaled down event more closely identified with the fraternities and sororities who sponsored it. Gone, too, were most of the hat societies-deemed by students to be elitist and anachronistic. Their function of recognizing superior scholarship was largely taken over by the professional honorary societies. However, at least one of the oldest societies-Lion's Paw-continued to recognize outstanding undergraduate leadership and in fact enjoyed a modest revival in student esteem.

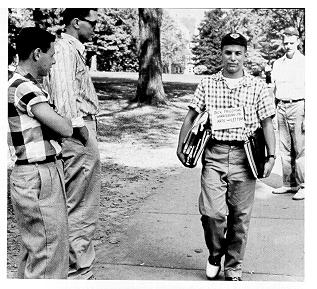

In 1955, freshmen walk the gauntlet of upper classmen.

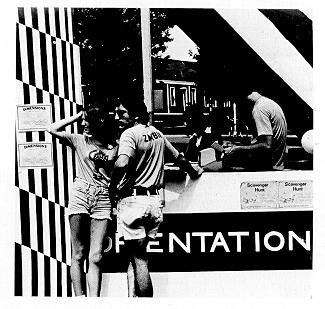

Orientation of the 1980s was intended to inform, not humiliate.

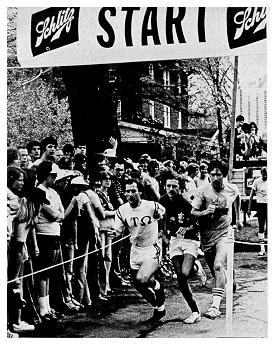

Starting the annual Phi Psi 500 on Locust Lane.

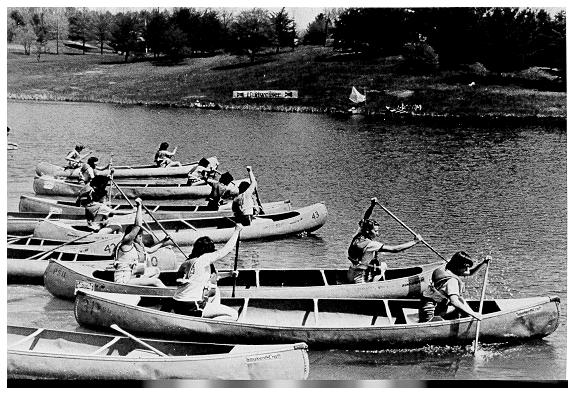

Another popular springtime fund raiser and social event was the Sy Barash Regatta. Named in honor of a prominent State College businessman and civic leader who succumbed to cancer in 1974, the regatta was first staged a year later and pledged its proceeds to fight that disease, It was sponsored by Beta Sigma Beta (of which Barash '50 had been a member) and held at Stone Valley until 1983, when the need to accommodate upwards of 15,000 people caused its removal to the more spacious Bald Eagle State Park. In addition to the nautical competition itself, the regatta featured picnicking, music, and other forms of diversion. By the end of its tenth year, it had raised in excess of $100,000 for the Centre County unit of the American Cancer Society.

Sy Barash Regatta canoe races, Stone Valley.

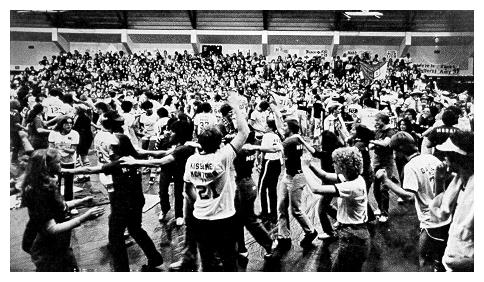

The largest charitable event-in fact, according to its sponsors, the largest fund raiser of its kind on any college campus by the early 1980s-was the Interfraternity Council Dance Marathon, held annually each winter since 1973. Soliciting advance donations and pledges redeemable after the event, contestants attempted to endure the physical and mental strain of 48 hours of continuous dancing (in the early years in the HUB Ballroom and later in White Building). Proceeds were turned over to various local charities until 1977, when the sole beneficiary became the newly created Four Diamonds Fund at the Hershey Medical Center. The fund provided financial relief to families whose children were cancer Patients at the center and also supported cancer research and educational programs. The fourteenth annual marathon, held in February 1983, began with 502 dancers, 355 of whom were still dancing (after a fashion) when the last song was played; the contest raised a record $105,000.

IFC Dance Marathon, White Building, 1979.

Two of the most prominent organized extracurricular activities owed their birth to the campus upheavals of the Vietnam War era. The Free University, based on an idea proposed by an undergraduate speech communications class in 1970, consisted of a loosely structured, student-run system of classes. Its offerings were not only tuition-free, but also free of examination, strict scheduling, and University bureaucracy. Instructors were volunteers, and students enrolled because they had a desire to learn about a subject, not because they had to fulfill a degree requirement. In its early years, the Free University catered to radical tastes and attracted a large following of social and political activists. Enrollment peaked in 1972 with 1,500 students taking about 100 courses. Later in the decade, the number of students and courses declined, but the Free University became more community oriented and offered instruction on such topics as wine and cheese tasting, belly dancing, auto repair, and scuba diving.

Gentle Thursday 1980 sprawls from the HUB lawn to Old Main.

The Free University co-sponsored an extremely popular social event of the 1970s, Gentle Thursday. Gentle Thursday was proclaimed each spring and was supposed to be a "day of sharing," when students could show concern about each other and forget about academic pressures and campus politics. Crowds on the HUB and Old Main lawns listened to live bands, enjoyed food and friends, viewed films, and otherwise relaxed. Unfortunately, Gentle Thursday also became a day of self-indulgence, highlighted by numerous drug- and alcohol-related problems. Those excesses and the widespread truancy found in the local secondary schools on Gentle Thursday caused the event's demise in 1980.

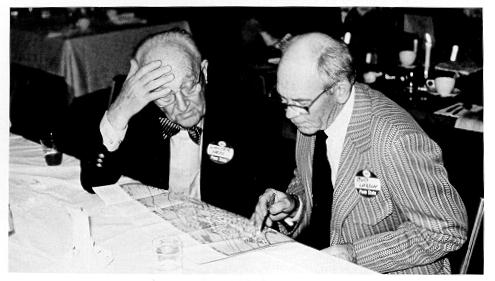

Reminiscing: two grads pause during an alumni gathering in 1978 to search the campus map for landmarks they knew well a half-century earlier.

In many ways Penn State students shared the kinds of experiences that fostered a camaraderie similar to that found at small colleges. Indeed, the Commonwealth Campuses were in many respects small colleges, and the friendships and institutional loyalties acquired there often remained strong long after students had transferred to University Park or had graduated. And the rural location of the main campus encouraged greater student interaction and firmer social bonds than probably would have been the case had Penn State been situated in an urban area with more external diversions.

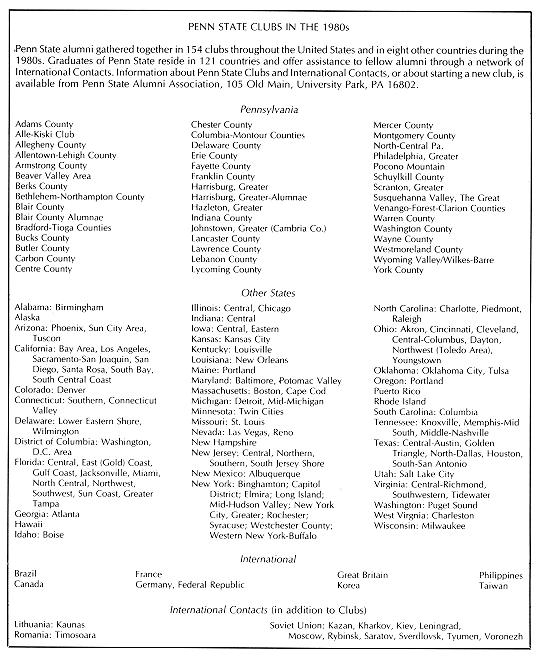

An extraordinarily large share of the University's graduates retained an interest in and commitment to their alma mater. In 1984, the Penn State Alumni Association ranked near the top among alumni organizations of all land-grant schools and state universities in both absolute size (70,000 dues-paying members) and portion of living graduates it included (about 26 percent). The association published the bimonthly Penn Stater magazine to keep its membership apprised of University personalities and happenings, and promoted a worldwide network of about 150 Penn State clubs. Graduates were encouraged to return to campus not only for football games and for the traditional October homecomings, but also for the five-year class reunions each June (which attracted some 1,200 alumni annually) and later in the summer for the Alumni Vacation College sessions (attended by 300-400 alumni and their families). In addition, each college had an alumni society (affiliated with the Penn State Alumni Association) with its own set of publications, faculty and student awards, and other activities.

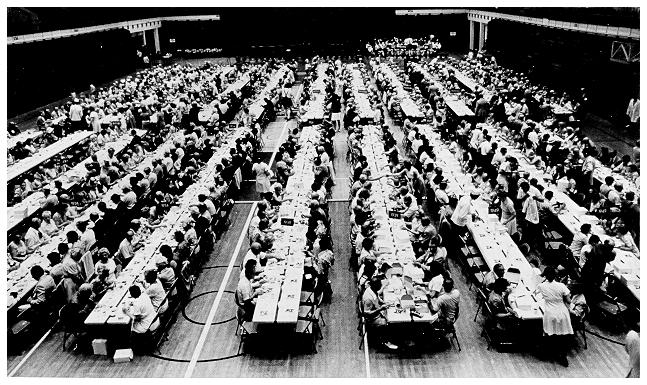

All-Class luncheon in Recreation Building during June reunion days, 1974.

To recognize outstanding professional and personal achievements of its graduates, the University conferred its annual Distinguished Alumni awards. In 1973, the board of trustees created another honor, that of Alumni Fellow. It was bestowed upon prominent graduates who returned to campus for as long as a week to lend their expertise and counsel to faculty and students in their colleges. Also, in 1973, the governing body of the Alumni Association, the Alumni Council, introduced the Honorary Alumnus award to recognize people who, though not Penn State graduates, had made valuable contributions toward improving the University's welfare and reputation. These contributions did not have to be financial: among recipients were Nittany Lion sculptor Heinz Warneke, football coach Joe Paterno, and emeritus presidents Eisenhower, Walker, and Oswald.

The University had a longstanding policy of not awarding honorary degrees, either to alumni or anyone else. In the case of the honorary doctorate, it made only four exceptions. It conferred that degree on William Buckhout in 1904, Louis Reber in 1908, President of the United States Dwight Eisenhower in 1955, and the chairman of the United Kingdom's Atomic Energy Authority, Sir Edwin Plowden, in 1958. Between 1911 and 1922, Penn State gave honorary master's degrees to alumni who returned for their class's fiftieth anniversary reunion and occasionally to commencement speakers.

Alumni had a vital role to play at Penn State. Their monetary contributions were channeled toward improvements to the physical plant, scholarships, modern laboratory equipment, better recreational facilities, and hundreds of other uses. Alumni recruited able students for the University, assisted its graduates in obtaining employment, and counseled educators on the needs of the world beyond academia. But most important of all, the alumni were the offspring of their alma mater's total historical experience. They were, in the words of Milton Eisenhower, "the real interpreters of the University to the people of the Commonwealth and the nation."