The selection of fifty-one-year-old Milton Eisenhower pleased nearly everyone at Penn State. Eisenhower was the first of the College's presidents to be well-known outside the academic community, and the fact that he was the younger brother of World War II hero General Dwight D. Eisenhower was hardly a liability. Faculty, students, and alumni had only praise for the incoming chief executive and looked forward to the decade of the 1950s with an optimism not seen for many years.

EISENHOWER AND THE COMMONWEALTH

Although he had been president of Kansas State College since 1943, Eisenhower had spent most of his career in government service. Born in Abilene, Kansas, he graduated from Kansas State in 1924 and took a position as American vice consul in Edinburgh, Scotland. Two years later, he joined the United States Department of Agriculture, serving first as administrative assistant to Secretary William M. Jardine (who had been president of Kansas State while Eisenhower was an undergraduate there) and then as director of information for the USDA. Eisenhower also handled special projects for the department. Following the outbreak of World War II, he became a troubleshooter for President Franklin Roosevelt. His most memorable assignment was as head of the War Relocation Authority, whose job was to move 120,000 Japanese-Americans from their homes along the West Coast to internment camps further inland. ("The most difficult and traumatic task of my career," Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs of his work with the WRA.) Even after he accepted the presidency of his alma mater, Eisenhower's administrative talents were still in demand by the government. In 1945, at the invitation of the secretary, he became involved in planning a reorganization of the Department of Agriculture. A year later he found himself heading the United States delegation to the United Nations Educational, Social, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), a responsibility he held until 1949.

In spite of these and other part-time public service diversions, Eisenhower was an energetic administrator at Kansas State. He led a movement to add more liberal studies to the College's technical courses and set in motion a multimillion dollar building program completed in time to meet a peak postwar enrollment of about 7,500 students. One of the achievements in which Eisenhower took greatest pride was his successful drive to rid Kansas State of official policies sanctioning racial segregation. By 1949, Eisenhower had attained all the goals he had set for his administration six years earlier and was eager for new challenges.

Eisenhower was not unfamiliar with The Pennsylvania State College. He had learned a great deal about the school from his work in the Department of Agriculture and had known Ralph Hetzel personally. In fact, Hetzel had asked him to consider becoming dean of agriculture upon Ralph Watts' retirement in 1937. Eisenhower was not aware, however, that James Milholland had sought the presidency of the College. He later reflected that had he been aware of Milholland's candidacy, he might not have come to Penn State. Too many problems could arise from having to work closely with a man who so recently had been his rival. Fortunately, the two men got along well from the start and enjoyed a close working relationship until Milholland's death in February 1956.

Shortly after taking office on July 1, 1950, the new president set out on the first of many fact-finding trips throughout the Commonwealth. Not wanting to repeat the mistakes of John Thomas, Eisenhower traveled an estimated 60,000 miles in Pennsylvania-most of them by car-during his first year. He did more listening than talking. He knew he had much to learn about Pennsylvania's people, economy, and politics. He especially wanted to know what the state's citizens thought of their land-grant institution and what they wanted it to accomplish.

In 1950-51, Penn State enrolled about 12,600 full- and part-time students, down from a postwar high of 14,800. The departure of the ex-GIs brought about some of the decline. The low birthrate in the early 1930s-the worst years of the Great Depression-also meant that fewer students were graduating from high school in the early 1950s. Nevertheless, educators throughout the country were predicting a sharp rise in college and university attendance later in the decade. The expected upswing in enrollment meant that Penn State would need a larger physical plant, more faculty, more laboratory equipment, and other necessities of higher education, all of which cost money.

A study completed during Eisenhower's first year in office revealed that the average yearly cost of educating an undergraduate at Penn State was about $600. A student who was a Pennsylvania resident paid only $220 a year in academic fees; most of the remaining $380 came from the state appropriation. The administration was reluctant to ask students to pay a larger share of their educational costs. Academic fees, while low by comparison to other schools in the Commonwealth (excepting the teachers' colleges), were already higher than those at many comparable land-grant institutions. Undergraduates at the University of Illinois, for example, paid an average of $116 per year in academic charges, at Ohio State University $135, and Purdue University $120. To Milton Eisenhower the implication of these figures was clear: the cost of earning a degree at Penn State had to be kept as low as possible, and the Commonwealth had to begin paying a larger proportion of this cost. He worked hard to cultivate good relations with Pennsylvania's political leaders.

Newly elected Governor John S. Fine in the spring of 1951 recommended to the General Assembly that Penn State be given $16 million for the 1951-53 biennium, $5 million more than the previous appropriation. Fine, a Republican, predicated that sum on the passage of a flat one-half percent income tax. Debate over this tax delayed the passage of a state budget until December. The legislature rejected the income levy (enacting a hodgepodge of nuisance taxes instead) and Fine's recommendation for Penn State. It gave the College $17.5 million.

Governor Fine was still worried that the Commonwealth's revenues were falling below its expenditures. In 1952, he appointed what came to be known as Pennsylvania's Little Hoover Commission to find ways of cutting the cost of government. Chaired by retired Bell Telephone executive Francis J. Chesterman, the commission released a preliminary report of its investigation into the Commonwealth's educational policies in December 1952. The panel maintained that the state should cease financing expansion at Penn State. Enlarging that institution's capacity was not economical, because it only attracted more students from eastern and western Pennsylvania, who had to live away from home and thus pay more for their education. The commission suggested that the General Assembly increase appropriations to the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Pennsylvania, and Temple University, all of which were located in metropolitan areas and within commuting distance of far more students than was Penn State.

A College spokesman denigrated this recommendation as typical of "the supermarket attitude toward higher education," but for the most part the Eisenhower administration remained silent on the report. The wisdom of taking a low-key response soon became apparent. The commission's findings contained a liberal sprinkling of political hot potatoes which few state leaders, including Governor Fine, would touch. Among the most controversial recommendations was one that would require graduates of the state teachers' colleges to teach in Pennsylvania schools for two years or else repay the state for the cost of their education. (The teachers' colleges were heavily subsidized.) Under this procedure, half of these institutions could be phased out and the Commonwealth's demand for teachers still be met. The report of December 1952 was only preliminary, released to test political reaction. When the final document was issued three months later, many controversial recommendations had been deleted or watered down, and the reference to cutting back Penn State's appropriation was nowhere to be found. Indeed, the College's allocation was increased to $20.5 million for 1953-55.

Penn State owed much of its success in financial dealings with the Commonwealth to Milton Eisenhower's long experience in politics. He and his assistant for legislative affairs, Charles S. "Sam" Wyand, a former professor in the Department of Economics, carried on an effective campaign to convince political representatives of the value of increasing state support for the College. A shift of political control to the Democratic party did not upset Harrisburg's good will toward Penn State. Democratic Governor George Leader in April 1955 asked the General Assembly to allocate $25.2 million to the College, the precise amount Eisenhower had said the institution needed. Passage of the budget was held up over Leader's proposal to boost the sales tax (enacted in the Fine administration) from one to three percent. The stalemate was not resolved until March 1956. At that time, Penn State had the singular pleasure of receiving more money than it had requested. Members of the General Assembly, noting the College's enrollment had grown by about a thousand students since President Eisenhower had made his original request, added over a million dollars to the governor's recommendation, bringing the institution's total allocation to $26.6 million.

Boucke Building provided badly needed space for classes in business administration and economics.

The College also benefited from General State Authority projects. In December 1953, the GSA approved $2.7 million for construction of a multistory building containing sixty classrooms and offices for one hundred faculty members. An addition to the infirmary was also approved. This allocation came as work was just being completed on the $8.9 million GSA program launched in 1950. The classroom building (located along Pollock Road between the infirmary and the new physics building) was finished in 1957. Originally designated the Hall of the Americas, it was renamed Boucke Building (in honor of Professor of Economics Oswald F. Boucke) a few months before it opened. The expansion of the infirmary was completed in 1958, the year that the building's name was changed to the Ritenour Health Center.

In the middle of his campaign to rally support for Penn State's financial needs, Milton Eisenhower began to give serious consideration to changing the institution's name to The Pennsylvania State University. "I did my best to have people understand that The Pennsylvania State College was an instrumentality of the state with a perpetual guarantee by the legislature to support it as it carried out the basic land-grant act," Eisenhower said later, "and that the University of Pennsylvania, despite its name, was strictly a private institution receiving some public aid as a grant. Because of the difficulty of getting this understood, I turned to the task of changing the name of the institution to The Pennsylvania State University."

Eisenhower had little difficulty getting the board of trustees to approve the name change, and in September 1953 it was submitted to the State Council of Education for approval and to the office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, which officially recorded names of all bodies incorporated in Pennsylvania. As a matter of courtesy, College officials informed authorities at the University of Pennsylvania of the proposed name change and found no objections to it from that institution. The only legal requirement was to have the Centre County Court of Common Pleas approve the change of name. On November 13, Judge Ivan Walker gave the court's consent, and the following day The Pennsylvania State College became The Pennsylvania State University.

CURRICULAR AND RESEARCH DIVERSIFICATION

University status made appropriate the renaming of the various schools that comprised Penn State. In January 1954, the trustees approved the name "College" for each of the former schools (except the Graduate School) and made two minor changes: The College of Engineering became the College of Engineering and Architecture, and the new School of Business became the College of Business Administration.

The School of Business had been formed the previous July after more than fifteen years of lobbying by alumni, business interests, faculty, and students. Their cause had been aided greatly by a warning from the American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business that Penn State's commerce and finance curriculum could not be accredited unless it underwent fundamental reorganization. President Eisenhower favored making these changes within the framework of an entirely new administrative structure. Putting business on a par with the other technical and professional schools seemed to be a logical extension of the Morrill Act and would benefit the Commonwealth's economy in many ways.

By the fall of 1954, Business Administration had become the fifth largest college in the University, enrolling over 1,100 full-time undergraduates in eight majors: accounting, business management, economics, finance, insurance and real estate, secretarial science, trade and transportation, and marketing. Graduate courses were offered in accounting, business statistics, and economics. A program leading to the Master of Business Administration degree, initially designed for undergraduates who had little preparation in business subjects, was not begun until 1959.

Business Administration's first and long-time dean (1953-73) was Ossian R. MacKenzie, formerly assistant dean of the graduate school of business at Columbia University. A native of Maine and a graduate of the University of Montana, the well-traveled MacKenzie had done graduate work at Harvard, held a law degree from Fordham, and had worked in several finance-related corporate positions before going to Columbia. Not long after arriving at Penn State, he served notice that the era of the supposedly facile commerce and finance curriculum the days when "O & F" stood for coeds and fun or crocheting and fancywork-were at an end. Academic standards were upgraded. Aware of the truth in the old cliche about the curriculum being only as good as its faculty, the dean began to recruit an instructional staff that combined professional competence with youthful vigor and enthusiasm.

MacKenzie also revitalized the Bureau of Business Research and the associated monthly Pennsylvania Business Survey. When the Bureau was formed in the Department of Economics in 1941 (the Survey began publication several years earlier), almost no information was available on business activity in the Commonwealth except for the metropolitan areas of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, nor did a statistical index of statewide business activity exist. By the early 1950s, the Bureau had filled this void. Its staff made economic surveys of all regions of Pennsylvania, with much of the statistical information they compiled being utilized by local industrial development groups. The editors of the Business Survey monitored and analyzed changes in the state's economic climate and dispensed data to all levels of business leadership, from shopkeepers to corporate executives.

Fine arts instruction includes pottery (left) and print making (right).

Curricular expansion took place in many areas besides business. Much discussion occurred concerning instruction in the fine and applied arts, most of which had been given by the Department of Architecture since the early 1920s. That department, in turn, came under the purview of the School (and later the College) of Engineering. As interest in the arts grew, however, it no longer seemed appropriate that such subjects be in an administrative division whose interests were chiefly technical. The disparity in educational objectives was made even more apparent in 1953 when a baccalaureate curriculum in the applied arts, consisting of courses in commercial art, interior decoration, costume design, and painting and illustration, was created within the architecture department. After exploring its options, the Eisenhower administration approved a plan creating the School of Fine and Applied Arts within the College of Liberal Arts. A Department of Art was formed using faculty in the fine and applied arts from the Department of Architecture. A new Department of Music was drawn from the music program in the College of Education, and a Department of Theatre Arts was created from the dramatics section of the Department of English Literature. The Departments of Art Education and Music Education in the College of Education and the Department of Architecture itself were affiliated with the new school, and sonic faculty held Joint appointments. This organization became effective February 1, 1956.

A variety of new degree curriculums were inaugurated within existing administrative units at about that same time. Engineering science, agricultural journalism, and labor-management relations were added at the undergraduate level, for example, and anthropology, child development, industrial arts, and mineral sciences at the graduate level.

Not all proposals for new curriculums could be implemented. In 1952, the State Council of Farm Organizations, representing thirty statewide agricultural associations, began agitating for the establishment of a school of veterinary medicine at Penn State. Advocates of the school argued that the 50 to 75 veterinarians graduated annually from the University of Pennsylvania, which operated the Commonwealth's only existing veterinary school, were insufficient to meet the growing need for professional care of large farm animals. Opponents claimed that the new school would cost at least $6 million, whereas Penn could double the size of its veterinary enrollment if given a $1 million boost in its state appropriation.

President Eisenhower and administrators in the School of Agriculture discussed the matter with officials from the University of Pennsylvania and found them to be absolutely opposed to a second veterinary school for the state. They feared that their modest legislative appropriation for veterinary work would be reduced to insignificance by the competition of another school. A compromise was then reached whereby Penn State would maintain its preveterinary curriculum and undertake research in veterinary science but train no veterinarians. The University of Pennsylvania would not use its political influence to oppose appropriations for such research. In 1953, the General Assembly allocated $100,000 for a new veterinary research center at Penn State. A new Department of Veterinary Science was created to assume responsibility for work at the center and for the existing preveterinary undergraduate program.

Penn State's research program was beginning to compare favorably with those of many other public universities. Expenditures for organized research rose from $4.8 million in 1949-50 to $6.5 million in 1954-55, fully 23 percent of the University's operating budget of $28.6 million that year and about 3 percent of the national total for research among land-grant and state universities. (By comparison, basic instruction accounted for 26 percent of the budget and extension and public service 17 percent.)

Engineering and Architecture, which led all colleges in research spending, owed its prominence to the Ordnance Research Laboratory, whose expenditures averaged about $2 million annually. Nearly all of that amount came from the Navy Department and other defense agencies. The ORL continued to be the Navy's principal center for the research and development of certain kinds of under water weaponry. Its staff was beginning to conduct investigations on submarine-fired guided missile systems as well as on torpedoes and underwater body shapes in general. The Department of Engineering Research superseded the Engineering Experiment Station in 1952 as the coordinator of most sponsored research done by the academic departments. Engineering faculty were still active in the study of heat and moisture transfer in building materials and of internal combustion engines-two subjects that had been attracting interest at Penn State for decades. Research in other fields-acoustics, hydraulics, the ionosphere, and computers, to name a few-was also getting under way, although on a modest scale. In July 1956, Penn State became one of the first universities to construct and operate its own electronic computer when faculty in the Department of Electrical Engineering completed work on PENNSTAC, short for Penn State Automatic Computer.

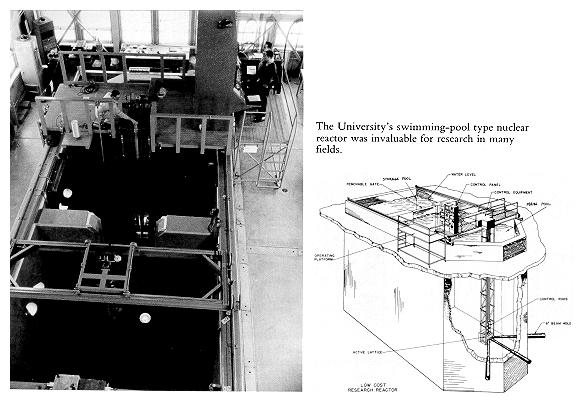

Of tremendous potential use as a tool for interdisciplinary engineering and scientific research was the nuclear reactor, plans for which were announced by President Eisenhower early in 1953. The guiding hand behind the construction of a reactor for Penn State belonged to Eric Walker, who had become Dean of Engineering following Harry Hammond's retirement in 1951. Walker foresaw the day when nuclear engineering, then in its infancy, would have to be taught as a curriculum in its own right. He asked his friend William Breazeale, a physicist at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, to take charge of nuclear engineering at the University. Breazeale insisted that Penn State should have its own nuclear reactor as the centerpiece for research and instruction in nuclear engineering. He had designed and overseen construction of a swimming pool-type reactor at Oak Ridge and said he could do the same at Penn State for a cost of "only" $250,000.

The Jordan fertility plots in 1950.

The federal government's Atomic Energy Commission had exclusive control over the operation of nuclear reactors and the enriched uranium that fueled them. Only one institution of higher education, North Carolina State College, had succeeded in getting AEC cooperation to build a reactor, and in that case, the initiative had come from the government. But the North Carolina State reactor was a small one and was not yet capable of reaching criticality (the point at which a self-sustaining nuclear reaction occurs) until late in 1953. The acquisition of a nuclear reactor would put Penn State in the forefront of nuclear research among all American colleges and universities, and Milton Eisenhower and the trustees readily agreed to spend the necessary funds.

Beekeeping had been a subject of investigation for Penn State agricultural scientists since the nineteenth century.

Construction of the reactor got under way in May 1953. Located on the eastern edge of the campus and designed by Breazeale, it was to have an initial maximum output of 100 kilowatts and was to be used by engineering researchers and by any other qualified faculty whose investigations demanded production of short-lived isotopes, beams of neutrons, radiation-damaged material, or other services which a reactor could supply. Commercial applications for nuclear reactors had not yet been shown to be economically feasible. Therefore, there was little thought given to using the reactor as a facility to train nuclear engineers or technicians.

As to the possibility of endangering the community by placing a reactor on the campus, "no one even questioned it," recalled Dr. Walker. "We explained it to the townspeople. We said we would not build a dormitory within a certain radius of the reactor. That's why we put tennis courts out there, because you can scram tennis courts if anything happens." The thought of scramming tennis courts instead of dormitories may have been equally horrific to some persons. Yet from what was known even then about swimming pool-type reactors, the health hazards were less than those connected with internal combustion engines, with their lethal carbon monoxide.

The University's decision to build a reactor had come at a most auspicious time. The Atomic Energy Commission was in the process of formulating a new policy that encouraged colleges and universities to become partners with the government in atomic research, and in January 1954, it approved an allocation of the necessary quantity of uranium. On August 15, 1955, only thirteen years after the federal government's Manhattan project had produced the world's first self-sustaining nuclear reaction, the facility reached criticality. Penn State became the first institution of higher education in the United States to be licensed by the AEC to own and operate its own nuclear reactor. (The North Carolina State reactor was operated under a different kind of arrangement with federal authorities and was the second facility to be licensed by the Commission.)

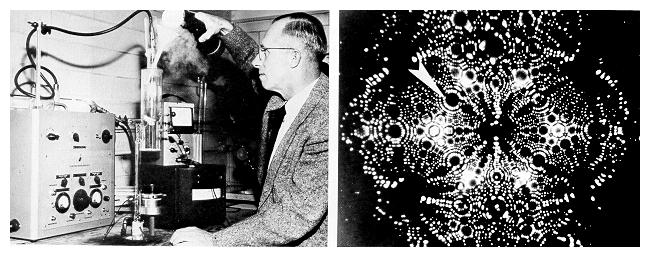

(Left) Erwin Mueller with a portion of the fiel-ion microscope; (right) a photograph made through the microscope—the arrow indicates a single tungsten atom magnified 2.1 million times.

Research in agriculture lacked such a glittering crown jewel as the reactor; however, thanks to many decades of federal and state support, the agricultural research program was more diversified and had a larger staff than those of the other colleges. Investigators at the Agricultural Experiment Station and other research units carried on hundreds of projects every year. A few illustrations can barely hint at their variety. Researchers working in the area of plant breeding developed many strains of crops and vegetation of significant value to the Commonwealth's agricultural economy. Pennoll wheat, for example, introduced in 1951, yielded an average of three more bushels per acre than most other varieties commonly planted by Pennsylvania farmers and had better milling qualities. In animal breeding, research in methods of artificial insemination wrought significant improvements in the hardiness and productive value of the Commonwealth's dairy herds. Agricultural engineers designed labor-saving devices for poultrymen and developed an automatic mash feeder that came into wide use in the early 1950s by Pennsylvania egg producers.

The experiment station maintained three permanent field laboratories to deal more effectively with problems that affected special regions or agricultural economics of the state. The facility at Landisville, Lancaster County, was established in 1893 for experiments in tobacco culture but later became a center for more general work in soil fertility and vegetable plant breeding. The field laboratory at Arendtsville, Adams County, conducted a variety of investigations designed to combat plant diseases and insect pests that threatened the large commercial orchards in south central Pennsylvania. At the North East Laboratory in Erie County, work began in 1940 on ways to control the grape berry moth and within a few years expanded to find ways of combating many other pests in vineyards and orchards of that region.

The college having the third largest outlay for research, Mineral Industries, doubled its research expenditures between 1950 and 1955. It was hoped that scientific research could help stem the post-war decline of the state's coal and related industries. One of the most important investigations centered on perfecting ways of producing higher grades of coke-used by Pennsylvania steel mills-from the lower quality coal that comprised an increasing portion of the Commonwealth's recoverable reserves. Another project sought to develop more efficient techniques for burning coal in large furnaces, such as those used in electrical generating stations, so that coal could be made more competitive with alternative fuels.

In contrast to the work in engineering, agriculture, and mineral industries, research in the College of Chemistry and Physics had fewer apparent practical applications. Nevertheless, the results of basic research often contributed to the solution of very real problems. Researchers in the spectroscopy laboratory, for instance, developed techniques of scattering light waves so that specific molecules could be identified, thus giving industry a quicker method of analyzing chemical products. The single most significant achievement in research in the College of Chemistry and Physics- and a milestone in international scientific research-came in 1955 when Professor of Physics Erwin Mueller became the first person ever to see an atom. Using a field ion microscope of his own invention, Mueller was able to magnify these tiny electrically charged particles over two million times and project their images upon a fluorescent screen for viewing. His work at the University was an outgrowth of investigations he had begun in Germany in the 1930s and represented a giant step toward understanding the building blocks of the universe.

Research in the other colleges was still sporadic and usually left to individual initiative, with such exceptions as the Bureau of Business Research, the Institute of Local Government, and the College of Education's Speech and Hearing Clinic. This is not to say that the quality of research in the non-technical colleges was inferior or that individual accomplishments were insignificant. Professor of Psychology C. Ray Carpenter, for instance, conducted a series of investigations that captured the interest of professional educators nationwide.

In the 1940s, Carpenter began pioneering studies in the use of motion pictures as teaching tools. He wanted to determine how films could best be integrated into classroom instruction and what qualities made them most effective. Eventually he became equally curious about the use of television for instruction. In 1954, the Ford Foundation provided financial sponsorship for a project designed to assess television's usefulness in solving problems associated with large class size. Carpenter used closed circuit television for classes in chemistry, psychology, accounting, economics, political science, and electrical engineering, among other subjects. In some cases, lectures were given to large classes via television and followed by a dispersal into small sections for more personal attention from instructors. In others, professors gave the lectures in person and used television to demonstrate laboratory techniques. Results indicated that in spite of certain liabilities, television was a valuable tool that educators could use to cope more efficiently with larger classes.

A major hindrance to research in the non-technical colleges continued to be the lack of an adequate library. In the late 1940s, the General State Authority had financed additions to Pattee Library (so named by the trustees in 1950) that nearly tripled stack capacity to about 600,000 volumes. Yet by 1955, Pattee and its small branch libraries in engineering, mineral industries, agriculture, and chemistry and physics contained only about 400,000 volumes. A study proposed by the Association of Research Libraries placed the University 51st in total holdings among 58 institutions surveyed. In 1956 Penn State's candidacy for membership in that prestigious organization was rejected, while Purdue, Rutgers, Florida, Michigan State, and other land-grant institutions were invited to Join. The University's library also fared poorly in comparison to the holdings of libraries at the University of Pennsylvania (1.2 million volumes) and the University of Pittsburgh (500,000 volumes) in the early 1950s.

Year after year, the University allotted an average of about 1.5 percent of its total budget to the library, ranking it near the bottom among the country's fifty largest institutions in the portion of funds going for library support. The low priority given the library came in spite of the best efforts of Ralph McComb to enlarge the University's holdings. A graduate of the University of Chicago Graduate Library School, McComb had succeeded Willard Lewis as head librarian in 1948. Like his predecessor, McComb bore the burden of having much responsibility with little authority. Political strength lay with the deans and department heads, particularly those in the technical colleges, who gave greater priority to meeting the immediate instructional needs of their undergraduates than to building a strong research library. The head librarian was outside this circle of power, even though the library existed to meet the needs of all University departments. Nor, unlike the deans, could the head librarian call upon ranks of influential alumni for assistance. President Eisenhower was sympathetic, but he devoted no more resources than his predecessors to building a library that met Penn State's needs.

AN ERA OF GOOD FEELING

More money would not solve all of the University's problems. Milton Eisenhower discovered that a certain amount of ill will had imbedded itself in relationships between the administration and the faculty, the administration and the students, and even between the institution and its alumni. Much of this discord had arisen from the lack of a full-time president during several of Penn State's most critical years. Eisenhower regarded the reestablishment of harmonious relationships between Penn State and its constituent groups as one of the most important objectives of his administration.

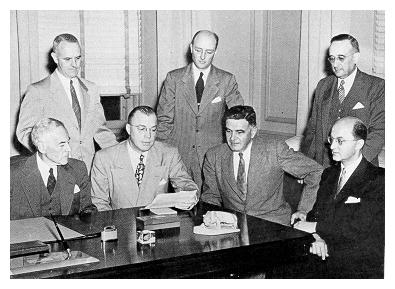

Surrounding Milton Eisenhower are his chief assistants (from left): A. O. Morse, Richard Maloney, Wilmer Kenworthy, J. Orvis Keller, Samuel K. Hostetter, and C. S. Weyand.

The President reorganized his administrative staff to convey more clearly to the faculty that his subordinates had the power to make important decisions. He eliminated the cumbersome "Assistant to the President in Charge of. . ." title that Hetzel had introduced. Eisenhower did retain most of the former president's staff, however. A. O. Morse became Provost, with responsibility for administering academic programs. Samuel Hostetter became Comptroller as well as Treasurer, thus expanding his powers as the institution's chief financial officer. J. Orvis Keller was given the new title of Director of General Extension, while Wilmer Kenworthy was made Director of Student Affairs. Kenworthy, formerly President Hetzel's executive secretary, had been Assistant to the President in Charge of Student Affairs since 1947, acting as liaison between the president and the deans of men and women.

The faculty had for several years been striving for higher salaries and a greater influence in administrative policy making. The increases in Penn State's legislative appropriation enabled Eisenhower to raise salaries substantially over just a few years. The average compensation of a member of the instructional staff (excluding ORL) in 1949-50 was $4,400; six years later it had increased to nearly $6,000. To improve communications between faculty and administration, Eisenhower in 1951 created the Faculty Advisory Council, consisting of twenty-five delegates elected from the faculty of the undergraduate schools and the central extension division. Unlike the University Senate, the Council had no power of its own; the president used it principally as a barometer of faculty opinion on specific questions. The Senate was top-heavy with administrators, deans, and department heads (all of whom were excluded from the Council) and its proceedings were too ritualistic for the kinds of informal relations Eisenhower preferred. He also made a practice of addressing the entire faculty every semester, reporting on the status of current issues and answering questions. The pay raises, the Advisory Council, and these semiannual convocations gave a badly needed boost to the morale of the teaching staff.

Eisenhower took a similar approach to bettering relations between the administration and the student body. He made himself available to student leaders, much in the style of Ralph Hetzel. The students rewarded Eisenhower by bestowing upon him the time-honored title of "Prexy." Robert Davis, outgoing All-College president, formally conferred this designation (to the president's genuine surprise and delight) at the Honors Day ceremonies in May 1951. "The trustees can appoint a President, but only the students can dub him 'Prexy,' " remarked Davis. "It has become quite obvious that the door to the President's office swings on well-oiled hinges. It is open and accessible to students-as much as possible during the day and often many hours at night."

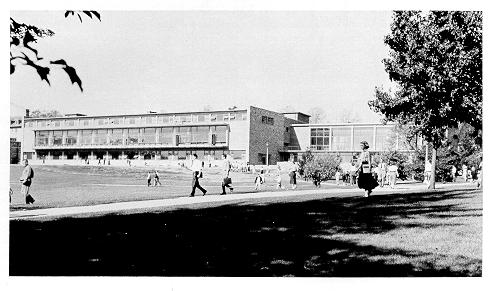

The HUB lawn was once Holmes field, preferred site of class scraps.

Eisenhower had achieved an excellent rapport with students at Kansas State. One of the most valuable means he had used to facilitate communication between administrators and students was Encampment, a series of informal meetings and recreational events in which administrators, faculty, and students participated for several days prior to the beginning of the fall semester. He saw no reason why Encampment could not be equally worthwhile at Penn State. In September 1952, Encampment was staged at the Mont Alto Campus and attended by a hundred or so students, faculty, and administrators. The intimate setting of Mont Alto was selected to minimize the adversary relationship that invariably permeated relations between administrators and students. Encampment proved to be so popular that it was held again the following year and thereafter became an annual tradition.

Eisenhower also worked closely with Lion's Paw, a senior men's honorary, in much the same way he did with the Faculty Advisory Council. He used it to gauge student sentiment on selected issues and to communicate his own feelings to the student body. Lion's Paw had been formed in 1908 to unite the leaders of various student groups for service to the College. Its most well-known project was undertaken in 1945 with the purchase of 517 acres of land on Mount Nittany to protect that landmark from lumbering and other commercial development.

The most tangible monument to improved relations between Penn State and its student body in the early 1950s was the construction of a permanent student union building. On at least two occasions late in the previous decade, undergraduate leaders suggested that the College levy a special assessment on each student to underwrite the cost of a union building, but the All-College Cabinet never adopted the proposal, and the administration would not agree to it. Acting President Milholland did approve the formation of a special Student Union Committee, composed of administrators, faculty, and students, to give the question more thought. After it became obvious that a majority of students wanted a new union building, the committee prepared tentative plans for the structure and the All-College Cabinet voted to ask the trustees to charge the cost to the student body. The Cabinet requested a fee of $7.50 per student for each semester in 1950-51 and $10.00 per student for each semester thereafter until the necessary funds were raised. In June 1950, the trustees approved the special levy and consented to the general design for the building and its proposed location on Holmes Field, across Pollock Road from Osmond Laboratory.

The Korean War then intervened to delay further progress. Construction materials could not be acquired until approval was obtained from the National Production Authority, which Congress had created to allocate potentially scarce resources that might be needed for national defense. Ground breaking for the Hetzel Union Building, or the HUB as the new structure was called, did not occur until January 1953. In contrast to most other campus buildings, the new brick and steel HUB was modern in its architectural style. It housed a lecture hall, ballroom, cafeteria, snack bar, study lounges, game rooms, and office space for student organizations. Formal dedication occurred on Penn State's 100th birthday, February 22, 1955. George L. Donovan '35, who as coordinator of the student social and recreational activities had been influential in the conception and planning of the building, was named manager of the new student union.

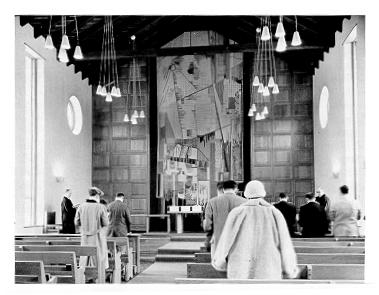

That same day the nuclear reactor facility was also dedicated and ground breaking ceremonies were held for a new all-faith chapel. The chapel, financed by private contributions, was located near Curtin Road on the edge of "Hort Woods." It was named in memory of Helen Eakin Eisenhower, the president's wife, who had died the preceding July. Eisenhower Chapel was intended to be a small wing of a larger building that was to be erected as soon as additional funds could be raised.

Alumni had contributed a significant portion of the $250,000 cost of the chapel. Eisenhower was eager to improve Penn State's relations with its graduates, whose numbers were growing more rapidly each year. In 1940, Penn State had awarded its twenty-five thousandth degree. Only twelve years later it conferred its fifty thousandth degree! "At any given time," the president wrote, "the true worth of the University is judged less by what it may be doing for its undergraduate body than by what it has already done for its students and graduates." And it was these graduates, he noted, who were "the real interpreters of the University to the people of the Commonwealth and the nation."

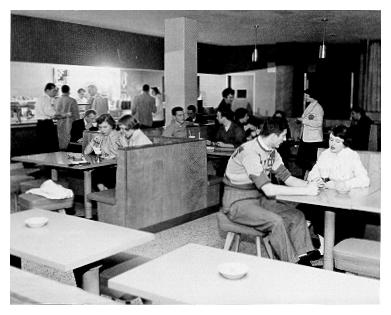

One of the most popular offerings of the new Hetzel Union Building was its food service, especially at lunch time.

Relations between Penn State graduates and their alma mater and especially the Alumni Association had occasionally been discordant since the 1930s. Criticism varied on specifics, but in general many alumni believed that the Association had become too lethargic. During the Great Depression, younger graduates said the Alumni Association offered no assistance in finding jobs. This was the principal theme of a group of Pittsburgh-area alumni who in 1939 organized a short-lived Alumni Committee of 100 as an alternative to the Association. Some graduates believed that the Association should engage more extensively in political lobbying in Harrisburg to increase the biennial appropriations. The leadership of the Association was also castigated from time to time for being content to live with-indeed, even relishing-the cow college image of Penn State and for failing to publicize its more modern aspects. The problem was not one of alumni apathy. It was rather one of getting the institution, its graduates, and the Alumni Association to set common goals and work in harmony.

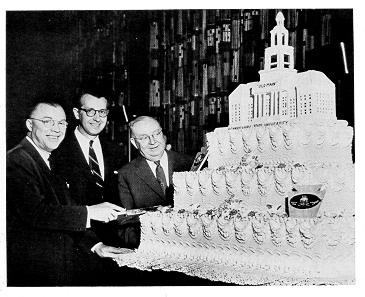

Milton Eisenhower, Governor George Leader, and James Milholland pose with the Penn State birthday cake prepared as part of the ceremonies observing the University's centennial in February 1955.

Ridge Riley '32 had taken over as executive secretary of the Alumni Association in 1947 and tried to rejuvenate the organization, but lack of encouragement from the highest levels of the College limited his accomplishments at first. Milton Eisenhower had worked closely with Kansas State alumni and was more receptive to Riley's ideas. As their initial step in improving alumni relations, the two men created the annual Distinguished Alumni awards. The first of these awards, presented at the Honors Day Convocation in May 1951, went to five persons: Charles E. Denney '00, former president of the Erie and the Northern Pacific railroads; Clarence G. Stoll '03, retired chief executive officer of the Western Electric Corporation; Bayard D. Kunkle '07, a vice president with General Motors; Ray I. Throckmorton '11, dean of agriculture at Kansas State College; and George D. Stoddard '21, president of the University of Illinois.

In June 1951 an Alumni Institute was offered. The institute consisted of a series of lectures, panel discussions, and other types of programs given by faculty on topics spanning the gamut from current political issues to recreational activities and hobbies. The institute coincided with the annual five-year class reunions and was designed to bring an educational aspect to these affairs. The response was enthusiastic, and the Alumni Institute became a permanent fixture of these June reunion weekends.

The first group of Distinguished Alumni, 1951, meet with President Eisenhower. From left: Bayard D. Kunkle, Charles E. Denney, George D. Stoddard, and Clarence G. Stoll (Not pictured: Ray I. Thokmorton).

Eisenhower and Riley were also concerned that Penn State had no organized system for soliciting financial support from its graduates. Other land-grant schools had proven that alumni contributions could be an important supplement to state and federal assistance. According to an American Alumni Council report, the Ohio State University had received $250,000 in 1951 from its graduates; Cornell, $172,000; Purdue, $73,000; and the University of Minnesota, $72,000. Penn State's receipts were far below these amounts, principally because its trustees, fearing that the Commonwealth would reduce appropriations if too much money were raised from private sources, were reluctant to engage in fund-raising. However, the fact that more than twenty percent of Penn State's graduates were members of the Alumni Association-a good showing when compared to most other land-grant institutions-suggested that if the trustees could be convinced to permit it, private solicitation would be very successful.

That permission came in June 1952, when the board approved formation of the Penn State Foundation as the first step toward increasing the institution's income from private sources. The Foundation had two divisions. The Alumni Fund received gifts from individual alumni, who could specify that their contributions be credited to an academic division or class fund. The Development Fund's primary objective was to solicit large gifts from corporations and foundations, especially to endow student scholarships and loans. Bernard Taylor, a consultant with twenty-three years' experience in college fund raising, was named executive director. The Foundation was an agency of Penn State, not the Alumni Association, and was not separately incorporated. Its twelve-member board, composed of trustees, alumni, and administrators, could suggest ways to spend money raised through the two funds, but the board of trustees made the final decisions.

Unlike the Emergency Building Fund drive of the 1920s, the campaign begun in the 1950s promoted annual giving. In its first year of existence, the Foundation raised $187,000, with over 7,900 alumni, or 15 percent of Penn State's living graduates, participating. By the end of the Foundation's third year, nearly $1 million had been received ($460,000 for the Alumni Fund and $509,000 for the Development Fund), and the alumni response rate had climbed to 28 percent. The money was used for projects that were considered necessary but were ineligible for state money-Eisenhower Chapel, for example. Combined with the steady increase in appropriations from Harrisburg, the money raised through the Penn State Foundation put the University in the best financial condition it had thus far known.

Eisenhower was not content to limit his policies of good will to the University's academic constituencies-faculty, students and alumni. He also saw the need to restore a feeling of friendliness between the University and the community of State College. "When I came to Penn State, the relations between the town and the College were terrible," he remembered. "I had been used to such marvelous relations at Kansas State that I was surprised by the hostility in State College." The behavior of fraternities, friction between landlords and tenants, and other points of contention between students and townspeople carried over from the 1930s and 1940s into the early 1950s. By then many residents of State College had begun to resent the changes in their community-the housing squeeze, increased traffic, higher police costs, more noise, overcrowded stores and sidewalks-that Penn State's postwar growth had brought about. Some residents had even lost money in that growth, in spite of the overall prosperity of the community, when the Borough-College Housing Corporation went bankrupt even before completing its first group of thirty-eight homes.

Eisenhower sought to end the widening rift. He called town and gown representatives together in a series of meetings to solve specific problems-the University's contribution toward the rising cost of fire protection, for instance. He also sponsored monthly luncheons where academic and town leaders could become better acquainted with one another and resolve minor gripes before they became major problems. The ill feeling between campus and community had persisted for so long, he believed, simply because the two sides had not talked to each other.

Just as town and gown relations seemed to be entering a new era of good will, a serious setback occurred. Ironically, Eisenhower himself was partly to blame. Not long after Penn State began calling itself a university, the president concluded that it was not in the institution's best interest to keep State College as its mailing address. In a letter to Herbert R. Imbt, a prominent businessman and president of the State College Chamber of Commerce, Eisenhower contended that the name Pennsylvania State University was not becoming established throughout the state and nation as he had expected. "Every press release issued by our institution carries the dateline State College," he told Imbt, "and this is naturally assumed by newspapers readers to be descriptive of the institution. Is it any wonder, therefore, that nearly everywhere newspapers, magazines, radio and television announcers, and even educational and industrial leaders refer to this distinguished institution as the State College?" Eisenhower concluded that the best solution to this problem would be to have the borough change its name, although he said he would not presume to suggest what the new name should be.

State College citizens debated Eisenhower's proposal throughout the summer of 1954. The borough council believed the most equitable way to resolve the issue would be to place specific names on the November ballot and let borough residents decide for themselves. Advocates of the name "Mount Nittany" (a group that included Imbt and the Chamber of Commerce) secured the required 10 percent of voters' signatures needed to place that name on the ballot. Supporters of other designations, such as Centre Hills and Keystone, also circulated petitions but failed to get the minimum number of signatures. In November, therefore, the contest would be between "State College" and "Mount Nittany."

Eisenhower gave his official backing to "Mount Nittany." The name was descriptive, it was likely to wear well, and there would be no conflict with the University title. Many borough residents thought "Mount Nittany" too rural in its connotation. Others opposed the name because they felt it had been chosen in an arbitrary manner. Still others resisted a change to any other name whatsoever on the grounds that "State College" had the weight of tradition on its side. Eisenhower did not help his cause when a few weeks before the balloting, he disclosed that he had urged the board of trustees to apply for a separate post office for the University. The University could then select whatever name it wanted for its mailing address. At the request of the president, the trustees had deferred action on the measure pending the outcome of the referendum. Some town residents saw this as a threat from the University, as an arrogant act of intimidation intended to force them to agree to Eisenhower's wishes. The results of the vote in November came as no surprise. "Mount Nittany" was defeated, 2,434 to 1,475.

Eisenhower moved at once to obtain a post office for Penn State. By early December, the trustees had authorized the sending of an application to the Post Office Department in Washington. The question of what to name the new facility, assuming it received approval and no one doubted that it would now that Milton Eisenhower's brother Dwight was in the White House-was to be settled in a democratic manner. Ballots listing seven choices were printed and mailed to all faculty, staff, and Alumni Council members and reprinted in the Daily Collegian and the Centre Daily Times. The easy winner was University Park, which won out over Atherton, Centre Hills, Keystone, Mount Nittany, University Centre, and University Heights.

Students enjoyed the convenience of using the new University Park post office.

The procedure for establishing a new post office or postal substation usually took many months or even years, but the University Park substation cleared bureaucratic hurdles in what may have been record time. Postal authorities approved Penn State's request within two months of receiving the application. The facility was located in the Hetzel Union Building and opened for business on the day of that building's dedication, February 22. On that date, it became the second post office in the nation to offer for sale a new three-cent stamp honoring Michigan State College and The Pennsylvania State University as the two land-grant schools having the oldest charters. (The stamp had gone on sale in East Lansing on February 12, the date of Michigan State's centennial.) Henceforth, University Park was the official address of Penn State and was used as the dateline for press releases and metered mail. Contrary to Eisenhower's expectations, the change did not entirely end the confusion with State College. That name remained a source of curiosity and continued to puzzle many persons long after the University's new address became effective.

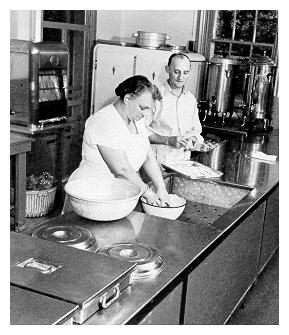

Food service employees prepared more than 2 million meals each semester for University Park students by the mid-1950s.

The unpleasantness arising from the debate over the new name for the borough was shortlived. More persistent discord came from a source least expected by the Eisenhower administration. In March 1952, Penn State's service employees-dining hall attendants, custodians, electricians, plumbers, groundskeepers, and other such workers-threatened to strike if their demands for better wages and working conditions were not met.

Penn State was Centre County's largest employer, providing jobs for over 1,800 service workers alone. A substantial number of these employees (estimates ranged between 300 and 800) were members of Local 67 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. One of the local's chief demands was to have Penn State recognize this union as an official bargaining agent. Many workers, whether or not they were union members, wanted the institution to work through grievance committees on issues connected with the reassignment and termination of employees and wanted to eliminate a supervisor's right to fire employees on the spot. Another important demand was equalization of the wage scale, linking it to the type of task being performed rather than the department or division to which the worker was attached. Service employees claimed that they were the forgotten men and women of Penn State, and that their wages, working conditions, and job rights had been ignored for too long. There was some doubt regarding the employees' legal right to declare a work stoppage. Pennsylvania law prohibited strikes by state employees, a category that included Penn State's service employees, based on their eligibility for benefits under the Commonwealth's retirement system. Conversely, these men and women were employed by an independently incorporated instrumentality of the state, not a state-owned or -operated institution. In that respect they were entitled to all the rights enjoyed by private-sector labor.

A few days before the scheduled strike, Eisenhower and Comptroller Samuel Hostetter met with employee representatives. There could be no recognition of any union-the trustees were firmly opposed to that-but Eisenhower and Hostetter did pledge the institution's good faith efforts to reach an accord on other issues. The workers found this response satisfactory enough to postpone a decision on walking out. In the weeks that followed, administrators and labor representatives reached a degree of understanding on uniform pay scales, grievance procedures, vacation policies, and similar matters. Not all differences were resolved. For the next several years, friction flared sporadically as employees sought to increase their gains and achieve what they argued the University had earlier promised them. The situation was further complicated in 1954 when a dissident group of employees, claiming lack of support from the national AFSCME organization, affiliated with Local 417 of the International Building Employees Union.

Although the trustees' executive committee in 1955 declared that the University did not object to its service employees organizing unions, the board gave no sign that recognition of any union as a collective bargaining agent would soon be forthcoming. Trustee leadership was in the hands of conservative industrialists like Roger W. "Cappy" Rowland '17 (president of New Castle Refractories), George H. Deike '03 (co-founder and president of the Mine Safety Appliances Company), and J. L. "Pete" Mauthe '13 (president of Youngstown Sheet and Tube)-men who did not have a high regard for labor unions.

PROBLEMS AND PROGRESS IN EXTENSION

The scope and content of Penn State's extension programs remained unchanged in the early 1950s. The mission was the same as it had always been: to make available the institution's resources, in a context not limited to classrooms and campuses, to those Pennsylvanians who desired education for continued professional and personal development. Agriculture and home economics still came under the supervision of agricultural extension, and the Division of General Extension (formally Central Extension) had charge of everything else. J. Orvis Keller, who had headed the Division of General Extension since its formation in 1934, retired in 1953. He was succeeded by his former assistant, Edward L. Keller, who continued his predecessor's basic policies. (The two Kellers were not related.)

General extension included instruction at the six undergraduate centers (Altoona, DuBois, Erie, Hazleton, Ogontz, and Pottsville), where from 10 to 15 percent of the undergraduate student body was enrolled. Day and evening technical institutes were operated in conjunction with some of these centers and in several additional communities as widely scattered as McKeesport, Scranton, Allentown, and York. The general extension staff worked in cooperation with faculty in Penn State's resident instruction departments to offer dozens of conferences and short courses every year in all parts of the Commonwealth. Faculty in the College of Mineral Industries, for example, regularly taught an extension summer short course in coal marketing. Liberal arts instructors gave extension courses in the social sciences to nurses who were in the pre-clinical phase of their training at state hospitals. General extension also administered instruction through correspondence, taken by thousands of students each year for college credit.

Some of the most important responsibilities of general extension defied categorization. The division maintained a large library of audio-visual materials that other colleges, secondary and elementary schools, and community groups could draw upon at nominal cost. The extension staff was also frequently asked to devise special review courses for persons planning to take professional licensing examinations, such as in accounting or insurance underwriting.

One of the most renowned agencies of general extension was the Institute for Public Safety, directed by Amos E. Neyhart. As an assistant professor in the Department of Industrial Engineering in the 1920s, Neyhart had become interested in why people would not or could not learn the techniques of safe driving. Hypothesizing that the trouble lay in improper training, he introduced the first high-school driver education classes in the country at State College High School in 1933. The response from students, parents, and teachers was overwhelmingly favorable, and Neyhart began training the nation's first teacher preparation classes in driver training. After organizing a national driver-training program under the sponsorship of the American Automobile Association, he became head of the newly established Institute for Public Safety in 1938. During the next several decades, this institute developed driver education and highway safety programs of all kinds for transportation companies, governmental agencies, schools, and nonprofit organizations.

The policies of the Division of General Extension came under fire from time to time for being too heavily weighted in favor of technical instruction. Most of the work of general extension-the technical institutes, the foreman training classes, the industrial conferences was geared to practical applications of knowledge, not humanistic studies. Because extension education had to be financially self-supporting, it was shaped by popular demand. Approximately 80 percent of the division's $2 million annual budget came from fees and other income received from services rendered. With few exceptions, the public was unwilling to pay for education that was not utilitarian.

One of the most popular forms of extension education had been the technical institute, but by the early 1950s, these institutes were losing their appeal. Their one-year course of studies was no longer sufficiently comprehensive, and high-school graduates preferred to earn college degrees rather than the certificates offered by the institutes. Yet the need was growing rapidly for persons trained in the application phases of technology, as contrasted with the theoretical aspects emphasized at the baccalaureate level. To meet the demand for engineering technicians, Dean of Engineering Eric Walker and Director of Engineering Extension Kenneth Holderman launched one of the most important educational ventures in the history of the University.

In 1953, two-year, full-time programs in engineering technology were begun at four undergraduate centers and five technical institutes. Two curriculums—in electrical technology and in drafting and design technology—were offered initially. Fewer than a half-dozen baccalaureate engineering institutions were then offering comparable instruction. To make them even more distinctive, Holderman received approval from the board of trustees to have the degree of associate in engineering conferred upon graduates of the new technology programs. The associate degree, a novelty in higher education at that time, also gave programs academic respectability, thus attracting some students who might have otherwise enrolled in four-year curriculums just for the sake of getting a degree.

More than 400 students registered for the two new curriculums in 1953-54. Within two years, enrollment had tripled and associate degree studies were being offered at twelve locations. A third engineering curriculum, metals technology, had been added. Dean Ossian MacKenzie of the College of Business Administration was quick to recognize the value of similar training in business subjects, and associate degree studies began at selected campuses in secretarial science and accounting. The College of Agriculture converted its long-standing two-year course in general agriculture to an associate degree program as well.

Three-fourths of the one million Pennsylvanians who annually partook of University extension were reached by the agricultural extension service. The system of county agents remained an important source of information for farmers on topics as diverse as planting Christmas trees, managing poultry flocks, and storing apples. Members of the extension staff also continued to provide agriculturalists with up-to-date price and marketing data according to specific commodities and geographic areas. They assisted 3,500 adult leaders and 30,000 youths yearly in 4-H Club projects and demonstrations. People did not have to live on farms or even in rural areas of the state to benefit from agricultural extension activities. Soil analyses, for example, were conducted at little or no cost for backyard gardeners, golf course superintendents, and anyone else having a need to improve soil fertility. Home economics specialists carried on their decades-old tasks of furnishing homemakers with information on preserving foods, especially through freezing, a technique that was rapidly challenging canning in popularity. Public schools still relied upon the expertise of extension home economists in planning nutritious lunch menus.

Milton Eisenhower had been personally involved in extension since his days in the U.S. Department of Agriculture and took a special interest in Penn State's agricultural extension work. He knew that a serious dispute had been raging for more than a decade between the University's extension agents and the federal government's Soil Conservation Service. The controversy arose partly over proprietary rights, that is, which agency was to do what kind of work with farmers in the realm of soil conservation. In addition, members of the extension staff argued that a fundamental principle of administrative control was at stake.

In the 1930s, the USDA had established the Soil Conservation Service as one of several action programs" to help farmers achieve the maximum income from their land consistent with its preservation and improvement. Pennsylvania was divided into four conservation districts, and federal agricultural agents arrived to teach the Commonwealth's farmers how to control erosion and otherwise make more efficient use of the topsoil. Penn State's agricultural extension service, which heretofore had not done much work with the problem of soil erosion, in 1935 organized a program to promote strip cropping, contour plowing, and other methods of conserving the soil. Extension agents believed that the Soil Conservation Service had a legitimate right to conduct research on that topic, but taking the results of that research to the farmer was the prerogative of the extension service. Officials of the SCS claimed they had a legal obligation to educate farmers and sent their own agents into the field to work alongside extension specialists.

Extension director Milton McDowell fiercely resisted what he considered to be an invasion by the SCS. He alleged that the conservation service's educational program was unnecessarily expensive. Its agents reached fewer farmers and incurred greater overhead costs than did extension agents, who made soil conservation part of their routine duties. Furthermore, McDowell said, county agents functioned strictly as educators, whereas agents for the Soil Conservation Service were in reality government regulators. The Roosevelt administration, through the Agricultural Adjustment Act and other New Deal legislation, had created a broad-based system of federal subsidies for farmers. Conservation service agents, McDowell warned, had the power to end subsidies to any farmer who did not follow "suggested" soil practices.

In 1941, a special committee of the General Assembly began an investigation of Penn State's agricultural extension service. McDowell claimed that the USDA and the Hetzel administration secretly asked for the probe as a means of putting pressure on the extension staff to call off what had become an open war with the Soil Conservation Service. Whatever the validity of McDowell's charge (the committee's findings were inconclusive), both President Hetzel and Dean of the School of Agriculture Stevenson W. Fletcher were distressed by the extension director's antagonism toward the SCS. Fletcher asserted that 90 percent of the Commonwealth's farmers faced soil erosion problems and were bewildered by the ill feeling between the county agents and the conservation service agents. They wanted cooperation, not conflict.

Fletcher seriously underestimated the farmers' allegiance to extension. He and Hetzel intended to reorganize the administration of the extension service once McDowell retired at the end of 1941. The dean of agriculture was also to become the director of extension. McDowell realized that the change was aimed to bring about cooperation with the Soil Conservation Service. With the help of Kenzie S. Bagshaw, master of the state Grange and a Penn State trustee since 1938, he arranged a meeting of 1,200 farmers, farm association leaders, county agents, and other agriculturalists in Schwab Auditorium on December 18, 1941. President Hetzel was also on hand., Before he had a chance to address the assembly, however, he was assailed by critical remarks from other speakers and jeered at by the angry audience. Incensed by what he later described as McDowell's "use of force," the President quickly retreated.

In spite of this antagonism, Fletcher succeeded McDowell as Director of Extension as planned. But J. Martin Fry, formerly McDowell's assistant, stayed on as assistant director and thwarted his superior's efforts to begin working in harmony with the conservation service. In July 1942, President Hetzel met with the agricultural representatives on the board of trustees and tried to get them to back a move to replace Fry with a more amenable subordinate. The president warned that the USDA might withhold funds for extension if Fry were not ousted.

The trustees countered by pointing out that the board had gone on record several years earlier as opposed to any cooperation whatsoever with the Soil Conservation Service, and that the USDA could not withhold any funds without Congressional approval. They refused to go along with Hetzel. After the meeting, in fact, they sent a statement to the other trustees explaining that what they learned in their meeting with the president convinced them "that there is and has been collusion between officers of the College and the USDA tending to nullify the policy of noncooperation [with the Soil Conservation Service] fixed by the board of trustees itself." A few weeks later, the trustees' executive committee removed the extension directorship from the dean's office and promoted Assistant Director Fry to that position. The anti-Soil Conservation Service forces had triumphed.

Noncooperation remained the official policy until Milton Eisenhower's arrival. He saw the controversy as an attempt by the extension service to protect its own administrative turf, not as a matter of principle. He also observed that until the Soil Conservation Service was formed, Penn State's extension agents had not shown much interest in soil erosion. If they had, perhaps there would have been no need for the SCS in Pennsylvania. These views were consistent with the role Eisenhower had played at the USDA where, as coordinator of land use planning, he had been closely associated with the conservation service. Indeed, some of the agricultural trustees were less than enthusiastic about his appointment as Penn State's president because they identified him as an enemy in their war with the SCS.

In return, Eisenhower regarded the agricultural trustees and their allies on the board as the main perpetuators of this war. "The agents of the extension service had been encouraged by the trustees to fight the Soil Conservation Service," he recalled. "That seemed incredible! Both were using federal dollars, yet snarling at one another. . . . The fight was notorious throughout the state." The president brought the full weight of his office and his prestige to bear on the trustees and finally convinced them that it was in the University's best interests to put an end to the fighting. The retirement of extension director Fry in 1953 also facilitated Eisenhower's peace-making chores. A truce with the Soil Conservation Service evolved only gradually and amid much grumbling by the extension staff, but in the end the victory belonged to Milton Eisenhower.

McCARTHYISM RESISTED

The post-World War II anti-communist crusade—a crusade so intense and so widespread that it verged on mass hysteria-reached its zenith in the early 1950s and made itself felt at nearly all of America's institutions of higher education. It was in part a product of the patriotic fervor that was left over from the war. Communists of any nationality had superseded German and Japanese fascists as the target of America's fear and hatred. Defeat of the dictators in 1945 seemed to have produced global insecurity rather than peace, for the cold war between the United States and the Soviet Union began almost as soon as the hostilities against the Axis powers ceased. Under the repressive leadership of Joseph Stalin, the Soviets dominated most of the countries of eastern Europe. Mainland China fell to the communists in 1949, the same year that the Soviet Union developed its own atomic bomb.

The invasion of South Korea by North Korea (with assistance form the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China) in June 1950 heightened Americans' anxieties over communist aggression. The discovery of several cases of Soviet espionage in scientific circles in America and other free-world countries indicated that even the home front was not secure. Supplying the explosive political spark to this highly volatile atmosphere was Wisconsin Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, who claimed that communist spies had infiltrated the State Department. McCarthy soon expanded his charges to include other agencies of the federal government, although he failed in every case to substantiate his attacks with irrefutable proof. His shrill and often vulgar campaign, relying heavily on innuendo and guilt by association, helped "McCarthyism" work its way into the language as a synonym for demagoguery of the worst sort. Caught up in the communist phobia, many Americans lent their support to McCarthy's efforts and to similar witch hunts conducted by the House of Representatives' Committee on Un-American Activities and various agencies at the state and local levels.

McCarthyism and the obsession with proving one's loyalty discouraged independent thought and encouraged conformity in academia. Many faculty and students hesitated to state their opinions on controversial issues or to join organizations that could in any way be interpreted as subversive. They had seen what McCarthy and others like him had dredged up from peoples' earlier lives to use against them as evidence of disloyalty. Men and women who had participated in left-wing causes in a naive, almost dilettantish fashion as undergraduates in the 1930s were twenty years later being scrutinized as security risks.

There was also talk on the campus about the Federal Bureau of Investigation recruiting students to spy on liberal professors, and about college administrators circulating blacklists of left-wing instructors whose employment could prove embarrassing to an institution; but like the rival allegations of the McCarthyites, most of these claims lacked proof. What was indisputable was that America's institutions of higher education were caught between two conflicting forces. They were expected to remain bastions of freedom of expression and yet were supposed to nurture patriotism, not disloyalty.

An incident occurring at Penn State in the waning days of the Milholland interregnum illustrated this dilemma. On April 1, 1950, Liberal Arts dean Ben Euwema informed Assistant Professor of Mathematics Lee Lorch that his contract would not be renewed for the following year. Dr. Lorch had Joined the faculty the previous September. Contract non-renewal could occur for any number of reasons, such as lack of funds for salary, decreasing enrollments, or personality problems. It was standard practice at Penn State, as at most other institutions, not to make the reasons public in, order to avoid Prejudicing the departing faculty member's opportunity to obtain employment elsewhere. Nor was it common to give a specific explanation to the faculty member himself.

Professor Lorch, however, believed he knew why he was not reappointed. In a statement released through the Progressive Party of Pennsylvania, a left-leaning political group to which he belonged, Lorch avowed that administrators were unhappy with his refusal to answer questions about his former association with the Communist party and with his activities on behalf of racial desegregation. Before coming to Penn State, Lorch had taught at the City College of New York and had taken a prominent part in a drive to open Stuyvesant Town, a new urban housing project, to black residents. Lorch had been dismissed from his CCNY position in 1949-again he said that his racial and political views were the cause-and while at Penn State he had allowed a black family to occupy his Stuyvesant Town apartment free of charge. He said that the decision against renewing his contract had ultimately been made by Provost A. O. Morse, who allegedly told the math professor that his crusades for equality in housing for blacks and his past affiliations with leftist political groups would damage the College's public image.

Lorch did not lack defenders in his attempt to get the board of trustees to review his case. His own department's promotion and tenure committee had recommended his reappointment. The Liberal Arts Students Council, the State College chapter of the NAACP, an ad hoc faculty committee for academic freedom, and the Daily Collegian all asked the administration to reconsider its action. The local chapter of the American Association of University Professors referred the case to the national AAUP leadership, which also asked for a review of the Lorch decision.

In mid-April, Provost Morse went before the College Senate and explained that Lorch's appointment had not been extended because of "personality conflicts," the same reason CCNY had given the previous year. After hearing the Provost's report, the Senate took no further action-a significant response, for it implied concurrence with Morse's views. The Senate's inaction also headed off a move by the student government on behalf of Lorch. Previously in favor of asking the trustees to reopen the matter, the All-College Cabinet took note of the absence of similar protests in the College Senate. After hearing the report of a five-member delegation sent to confer personally with Morse, the cabinet voted on April 20 by an 18 to 3 margin against taking further action. The Collegian too, swung away from its pro-Lorch stance and now asked only that the administration state the specific reasons for his dismissal.

Acting President Milholland refused. He issued a statement on April 25 simply denying that Lorch had been refused further employment on account of his racial or political views and stating that the professor "does not have the personal qualifications which the College desires in those who are to become permanent members of its faculty." That explanation shed no more light on the matter, but it did signify an end to the case. Lorch left to Join the faculty at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. There, he was again discharged (in 1953) for refusing to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee about his involvement with the Communist party.