When The Chestnut Street Female Seminary opened in 1850, private girls’ schools were just coming into vogue. With the advent of the gas light in the early 19th century, reading was becoming a popular pastime for women, who could now entertain and educate themselves in the evening after completion of their daily chores. Founders of private finishing schools saw the burgeoning market for secondary education that would allow young women to develop their intellectual skills while honing their social graces.

Unlike most of the new institutions, the Chestnut Street Seminary (fondly called “1615” by a century of students) did not advertise. A word-of-mouth network of the prominent and powerful recruited and recommended its clientele. The difficulty of limiting the students to “families of good American lineage” soon arose as bankers, businessmen, clergy, and educators throughout the country sought to add friends or acquaintances to the fashionable group. Eventually, alumnae in cities all across the country would survey the long list of applicants and identify the top candidates in an effort to keep the student body homogenous and exclusive.

Principals Mary Bonney and Harriette Dillaye originally opened their school at 525 Chestnut Street, but soon afterward, the buildings were renumbered and the address became 1615. By the second year, forty girls were schooled in the stately four-story brick row house at 1615, about half of them boarders, and this was just the beginning. In 1859-60, just one decade into the school’s history, there were 37 boarders and 50 day students!

It may have appeared “stately” from the outside, but inside the quarters were woefully tight. Sleeping rooms, designed to accommodate four students, measured about 10 by 15 feet, and the four girls shared a single bureau. There was only one dedicated classroom; classes were held in the trunk-filled attic or areas that doubled as bedrooms. Teachers’ bedrooms were the size of a small closet. Fifty people shared a single bathroom!

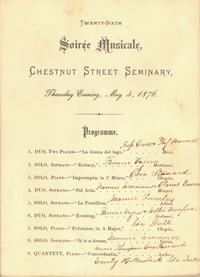

Though few records of graduates from these early days exist, it is clear that Mary Harrison of Indianapolis, daughter of president-to-be Benjamin Harrison, was a member of the Class of 1876. Others in her class came from Chicago, Illinois; Syracuse, New York; Fall River, Massachusetts—cities of industry and social status.

Bonney, Dillaye, and their well-educated faculty taught girls from about 13 to 17 years of age. The school Prospectus for 1857 offers insight into its educational mission to combine the substantial with the ornamental: “While it is the primary design of this Institution to secure to its pupils a thorough and extended education in the varied Departments of Literature and Science, much attention is paid to Music, Painting, Penciling, and Crayon.” Solidarity with Polish was the school’s credo. Some attention was paid, as well, to the girls’ physical well-being as calisthenics and walking were requirements of the curriculum.

Commencement day was also examination day, with parents and guests watching as each girl drew a card on which was written a topic from the text, Intellectual Philosophy, and had to expound on the topic before an examining committee to earn her diploma. Later, at Ogontz, this examination was still conducted, but not before guests, making the occasion happier for all concerned.

In 1883, Bonney, Dillaye, and their two new associate principals, Frances Bennett and Sylvia Eastman, accepted an invitation from Civil War financier Jay Cooke to rent his vast suburban estate, Ogontz, as the school’s new quarters. Once the move was made, The Ogontz School was adopted as the school’s new name and remained so for nearly 70 years.